In defense of the White House Correspondents' Dinner

Give the Nerd Prom a chance

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

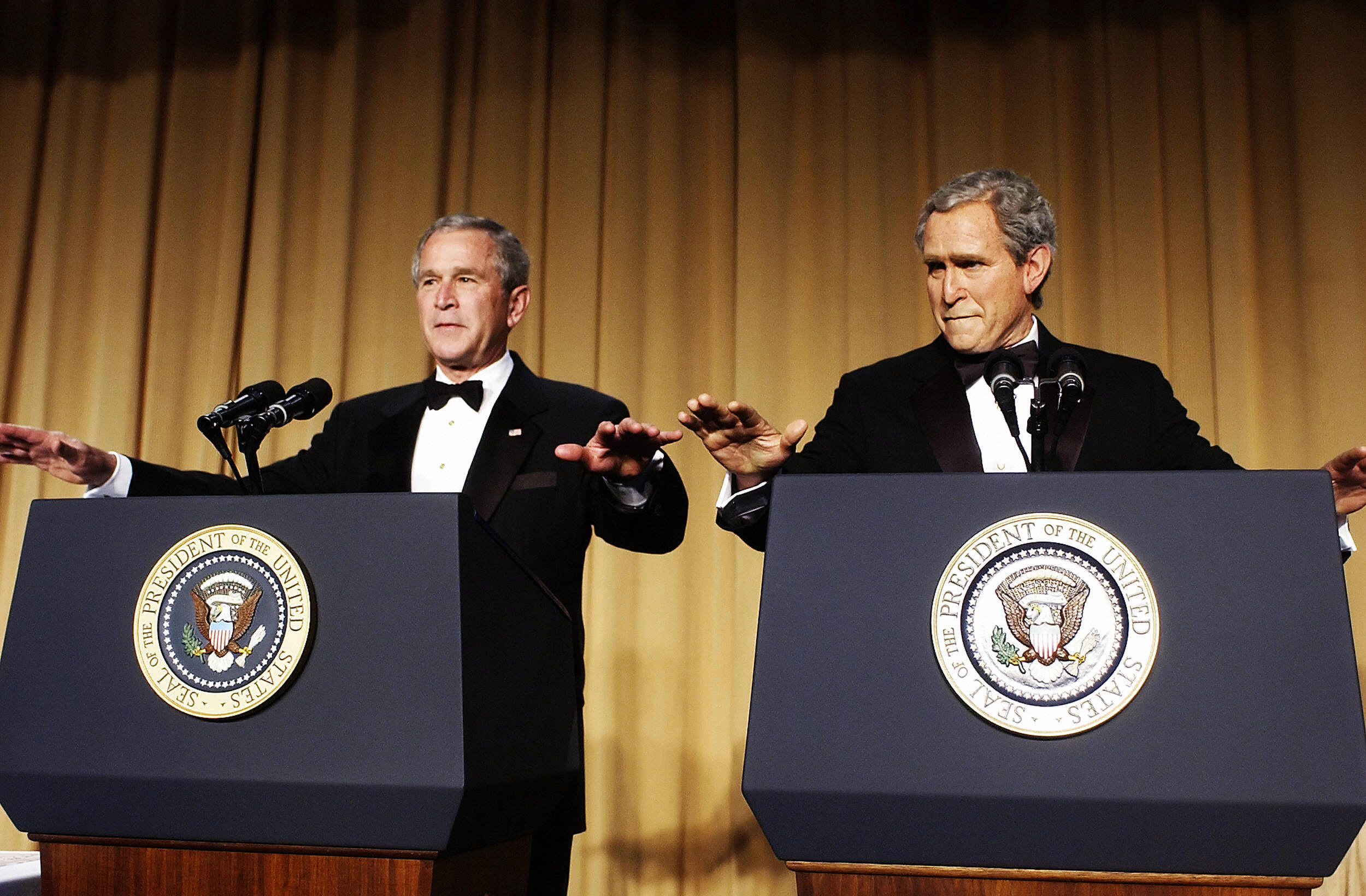

The latest skirmish in the "war" between President Trump and the media is the former's decision not to attend the annual White House Correspondents' Association Dinner, which famously features a roast of the president by a comic, followed by a comedy routine by the president. The immediate and near-unanimous reaction of those who care about such inside-the-Beltway events was something like: "Now maybe the thing can go away and die."

It's very popular among journalists to mock, or even seriously criticize, the "Nerd Prom." And, look, I get it. The "optics" (as they say in Washington) of the Beltway's reporters, who are supposed to be impartial towards power, hobbing and nobbing in tuxes with the man they're supposed to cover adversarially, are not great. And it's not just optics: Washington — as any reporting beat, really — does have problems with proximity and back-scratching between those being covered and those doing the covering. As a conservative who frequently whines about liberal media bias (why, just yesterday in fact!), I certainly understand quite well why it's not a great look when you have reporters laughing merrily at President Obama's jokes.

At the same time, I've always had a fondness, and even an admiration, for the White House Correspondents' Dinner. And this is because I come from France, where a tradition like this would be unthinkable. And like the fish in the joke who asks "What's water?", American journalists don't realize that the sheer existence of the dinner, in many ways, reflects what's best about their country.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

After all, if you take a global perspective, the ritual of making the nation's head of state sit at a table and endure a roasting by a comedian — even if it is a gentle roasting — and not only have to take it, but smile and laugh throughout, is really quite extraordinary. I don't need to play violin music and talk about countries where mocking power can land you in jail, or worse. My home country of France is a republic, thank you very much, and people here don't get intimidated by that kind of thing. But we still conceive of our presidents as democratically elected monarchs, and the idea of something like the White House Correspondents' Dinner would be unfathomable for us.

Even 150 years ago when visiting America, the thing that struck Alexis de Tocqueville most about the country was this spirit of social equality, which is reinforced by the country's cultural informality. Something like the Correspondents' Dinner could only happen in a country where enough people understand — and don't even have to be taught — that the head of state is, at the end of the day, just a person like everyone else, albeit one who happens to have a very important day job.

The whole institution of the comedy roast is a quintessentially American thing. Stand-up comedy is a uniquely American cultural export, like jazz or Hollywood. It refers back to that spirit of equality and informality. The roast reminds a prominent person, and everyone in the audience, that they are just a regular — and flawed — person like everyone else. It's a "Memento Mori" moment, which is an important thing for a society to have. The genius of the institution comes from the fact that in many cultures, a collective "taking down a peg" of someone prominent usually involves mob dynamics and leads to enforcement of social conformity. The fact that it's done through comedy lubricates the whole proceedings. Of course, comedy can be extremely cruel — more cruel than many other forms of retribution, in fact — but it's implicit that a comedy roast can't be too cruel. The trick is precisely to be neither too soft nor too hard. The comic whose roast is too hard will bomb, and she knows it.

Inspired by the American example, we once tried something analogous over here, and it was a massive failure. Political talk shows started inviting comedians to do a quick sketch about the guests. It was awful. Our comedians tend to be much more cruel than the winking comedy style found in the U.S., and it's one thing to be cruel to someone on a stage, and quite another to do it to their face. So comedians delivered their routines awkwardly, while their targets sat there stony faced, not understanding how to respond. Owing to our culture's Mediterranean shame-and-honor concepts, politicians rebelled, angrily defending "the dignity" of their "office." Which is to say they reacted with the opposite of good humor. But any U.S. politician knows that, however he feels inside, he must publicly display good humor towards mockery.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The Correspondents' Dinner, in other words, displays some of the qualities that make America a truly exceptional nation: a democratic and egalitarian ethos that is lubricated by informality and both leads to, and is fueled by, cultural innovation. It symbolically shows and reinforces some of the key qualities of the American experiment, namely that mocking those in power is not just something you can get away with, but an important social and political function, and that those in power have to be reminded that they are equal to the rest of their fellow citizens. Has that latter part ever been more important than it is with President Trump?

Give the Nerd Prom a chance.

Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry is a writer and fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. His writing has appeared at Forbes, The Atlantic, First Things, Commentary Magazine, The Daily Beast, The Federalist, Quartz, and other places. He lives in Paris with his beloved wife and daughter.

-

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'Cartoons Artists take on a girlboss, a fetching newspaper, and more

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’Talking Point Reform and the Greens have the Labour seat in their sights, but the constituency’s complex demographics make messaging tricky

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred