Scoffing at credulous Trump voters is not a winning political strategy

Sometimes, winning politics requires real sympathy for your opponents

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Since the election of Donald Trump to the presidency, there has been an ongoing debate on the American left about the proper posture to take toward his supporters. On one side of the debate, a rather old-fashioned brand of centrist liberals advocate a sort of operatic pity towards his disproportionately white and male supporters who were sold a working-class agenda on which Trump will never deliver. On the other side, many angry liberals openly celebrate Trump-supporting coal miners potentially losing their health insurance under the GOP's ill-fated American Health Care Act. Serves 'em right, the thinking goes.

Well, what role should sympathy play in politics? After all, simply scoffing at people who refuse to vote the way it seems their true best interest lies is no way to win an election.

Recall that while those white men who did vote — especially those without college degrees — voted for Trump in overwhelming proportions, white men are still only a minority of his total voters. Most of the arguments advocating no sympathy for Trump voters implicitly or explicitly characterize the victims as white men suffering some class oppression. But if one argues that Trump voters deserve what's coming to them, that also means some Trump-supporting women deserve the loss of Planned Parenthood, or perhaps even a small group of Trump-supporting minorities deserve racist oppression.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Desertist moral reasoning is extremely common in this country. So plenty of people would fully lean into the above logic. And indeed, such a morality is one of the foundation stones of American conservatism. It can easily lead to some bad places. Frank Rich, in his article "No Sympathy for the Hillbilly," favorably cites Kevin Williamson's vicious tirade against poor whites, and J.D. Vance's wretched book about poor Appalachian whites being welfare queens. The thought that poor whites are poor because of their bad decisions has a brother: that poor blacks are poor for the same reason, as Williamson has also argued.

Nevertheless, that does not mean a moral condemnation of Trump voters must follow desertist lines. One could condemn them for voting for a grotesquely incompetent bigot without endorsing the ensuing oppression. Or, one could weave some sympathy for poor whites into a stark moral condemnation of white racism precisely because "prejudice and blindness" has put poor whites "into the position of supporting your oppressor," to quote Martin Luther King, Jr.

And poorer whites are indeed paying a steep price. Racist suspicion of transfer programs is one reason why the American welfare state is so weak, and that in turn is almost certainly one reason why white mortality rates — especially among the lesser-educated — are dramatically higher than the rest of the developed world. And the gap is getting wider over time, as the latest Case-Deaton research shows. In my view, racism is a social poison that corrodes in both directions, though obviously the harm is worse on the receiving end.

In any case, the application of any such morality to politics is a different question. Egalitarian moral ideology transformed into leftist politics leads to an obvious goal: Assemble a coalition that will vote for a universalist economic and social justice agenda. Compromising the political platform to accommodate bigotry is out of the question, but conversely neither is it necessary for every single voter to be without moral blemish. A vote is a vote.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

No doubt a great many downscale whites are too racist to ever vote for such a leftist platform. But Rich's assertion that the very idea of trying to peel off enough of those people to win with good policy is "wishful thinking" is utterly ridiculous. Nothing in politics is guaranteed, but the fact is President Obama — who, let us not forget, is black — managed to twice assemble a winning coalition consisting of roughly one-third white people without a college degree. He did it with a strong working-class message.

Hillary Clinton gave comparatively little attention to class issues. The party platform was reasonably strong on the merits, but she largely ignored it in favor of attacks on Trump as a misogynist and a bad role model. Lack of uncomfortable talk about more taxes also helped with fundraising and a general party strategy of rolling up votes in wealthy suburbs. Her advertisements had the least policy content of any presidential campaign going back until 2000 at least, and by far. All that implicitly allowed Trump to own the issue of trade and jobs.

It can be maddening to think of credulous Trump voters who are about to be stripped for parts by Wall Street. But very often liberal arguments about these people are nothing more than this resentment with some political window dressing. If one actually cares about improving the lot of the (disproportionately black and brown) bottom half of Americans, one should never try to adjudicate in advance what large sections of the electorate to write off in advance. Instead, build a bold program of justice for minorities and the whole working class, and sell it as widely as possible.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

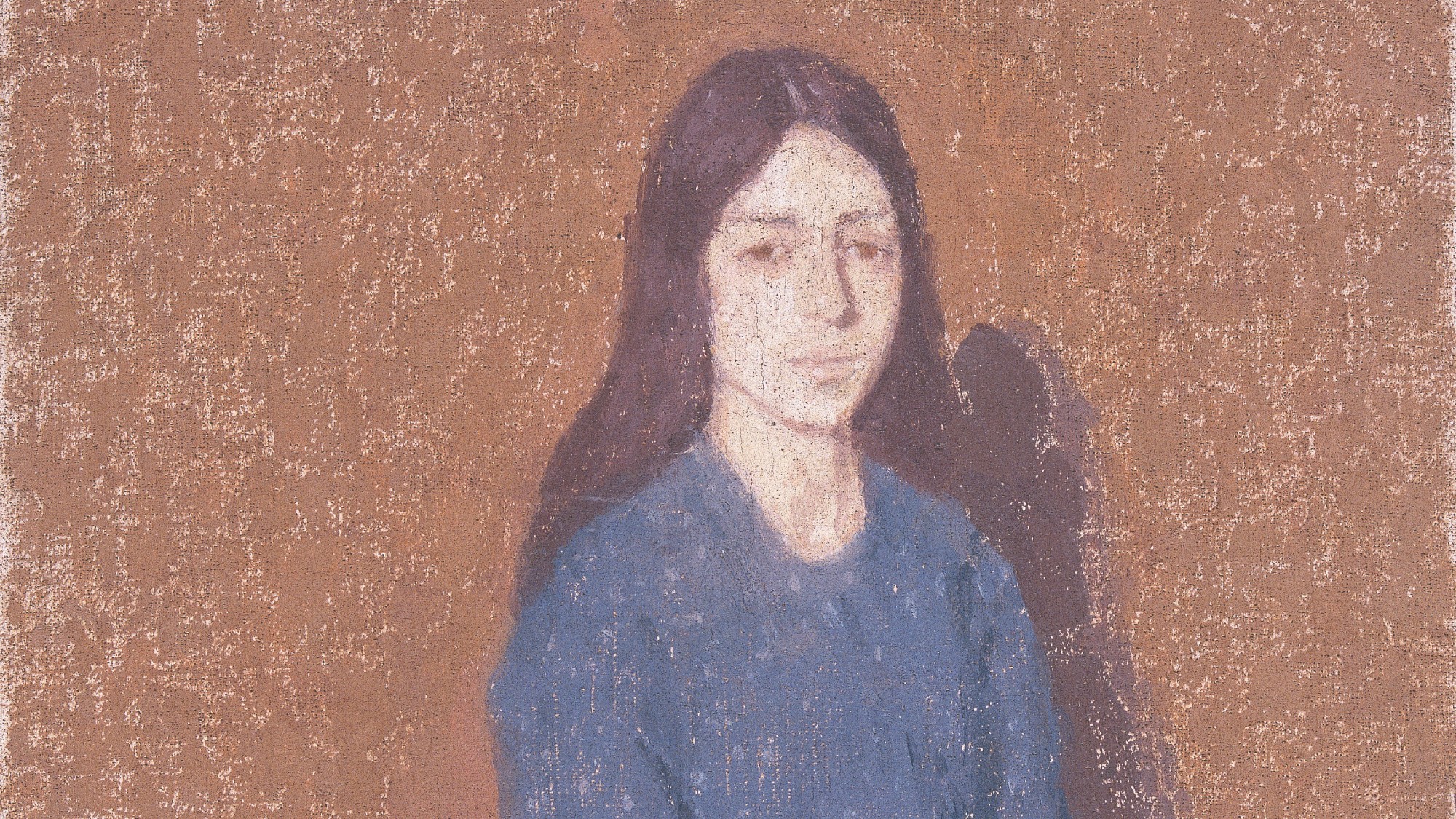

Gwen John: Strange Beauties – a ‘superb’ retrospective

Gwen John: Strange Beauties – a ‘superb’ retrospectiveThe Week Recommends ‘Daunting’ show at the National Museum Cardiff plunges viewers into the Welsh artist’s ‘spiritual, austere existence’

-

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?Today's Big Question After rushing to praise the initiative European leaders are now alarmed

-

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problem

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problemThe Explainer Before her appointment as cabinet secretary, commentators said hostile briefings and vetting concerns were evidence of ‘sexist, misogynistic culture’ in No. 10

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred