Syria is a dead end for President Trump

Here's why Trump should think twice before attacking Syria again

At first blush, President Trump's decision to launch reprisal airstrikes on Syria seems to have paid off. At least politically.

A CBS News poll taken over the weekend revealed that a bipartisan majority of American voters support the attacks on the Shayrat air base, from which Syrian President Bashar al-Assad launched the chemical-weapons attack on a small town in Syria. Fifty-seven percent favored the strikes, while only 39 percent disapproved. A Washington Post poll found a slightly narrower but still significant majority backing President Trump's military action, 51 percent to 40 percent. Some of Trump's fiercest critics on both sides of the aisle have praised his decisive reaction, and are pushing for a stronger American position on the Syrian civil war and Russian protection of Assad's dictatorship.

The reprisals appear to have had other salutary effects as well. Most of America's Western allies rallied behind Trump despite earlier differences on policies regarding Syria and refugees. After the strike, Chinese President Xi Jinping signaled a more cooperative approach to the nuclear standoff on the Korean Peninsula, and followed through with a refusal to offload coal from North Korea, cutting off Pyongyang's main source of hard currency. Russia has angrily protested the strike, but even that serves Trump politically at home, reminding everyone that Trump was less friendly to powers outside the U.S. than some of his critics imagined.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

These gains and the rare moment of bipartisanship might persuade Trump to pursue a more traditional Republican interventionist policy. But regardless of whether or not that is the correct policy, it's likely to become a trap for Trump, and a political dead end as well.

Politically, such a move would present a sharp reversal from the promises Trump made in the campaign to the anti-establishment voters who carried him to victory last November. More than most presidents, Trump has to rely on his base for political capital. Unlike Barack Obama, whose personal popularity saw him through political setbacks, or even George W. Bush, whose own promises of a more "humble" foreign policy fell by the wayside after 9/11, Trump has no personal-popularity margin for error.

Voters didn't rally to Trump's side last year because they found him likable; they supported him because they didn't like the Washington establishment and its policies, and elected him to disrupt both. Trump's professed "America First" policies that promised significant disruption to the interventionism in both Republican and Democratic administrations, a theme Trump constantly hammered during the campaign. At one memorable GOP primary debate, he openly accused Bush of lying to justify the 2003 invasion of Iraq, touching off a heated exchange with Jeb Bush, who defended his brother's policies and pledged to return to them. The Florida governor easily had the best campaign-finance operation in the primaries, but folded early as Trump soared — a lesson on the popularity even among Republican voters of interventionist policies.

The decision to strike Syria at this point has Trump voters scratching their heads, Byron York notes, especially because Trump has offered no explanation for the change nor expressed a coherent strategy behind it. The majorities in both polls are also deceptive, a Republican pollster explains to York, who points out that support for follow-up strikes are stuck in the mid-30s, and that the reprisal on Shayrat has not lifted Trump's overall approval ratings. Those are warning signs that Trump lacks a mandate for extending his new policy, especially without explaining how far the strategic change goes.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

That lack of limits presents another problem for Trump, too. Already, some in Washington want to see Trump go much further along the interventionist spectrum in Syria. After a fumble by press secretary Sean Spicer in mentioning "barrel bombs" as a potential red line (Spicer walked it back later), Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) told CNN that the U.S. should respond militarily if Assad uses barrel bombs. Calling this red line "long overdue," Graham argued that the principle and policy should focus on what happens on the ground, not necessarily the methods used. "It's not about how you killed the babies," Graham declared, "it's the fact that you're slaughtering innocent people through air power."

Applying that standard to the Syrian civil war may well be justifiable considering the brutality of Assad, but it would require a full-scale military intervention. That would produce a hot confrontation with Russia, which has been firm on its support for Assad, and with Iran too. That may still be the right action to take, but it would require a president who is temperamentally inclined toward such military actions, and a base of political support to enter a new war. Trump has neither; he is much more inclined toward insular policies, and the country clearly does not want to escalate the conflict, as both polls showed.

As conservative radio host and early Trump backer Laura Ingraham put it: "I'm not sure getting rid of Bashar al-Assad was at the top of the list of the people in Pennsylvania."

President Trump has achieved one important accomplishment with his reprisal strike on Assad's military: He has forced America's opponents to reckon with our potential response. That element has been missing for several years, and it is not without value. Unless Trump can make a case for being a war president with the commitment to see it through to the end, though, he would be better advised to stay out of the Syrian trap as much as he can, and hope that one example will be enough to keep antagonists guessing.

Edward Morrissey has been writing about politics since 2003 in his blog, Captain's Quarters, and now writes for HotAir.com. His columns have appeared in the Washington Post, the New York Post, The New York Sun, the Washington Times, and other newspapers. Morrissey has a daily Internet talk show on politics and culture at Hot Air. Since 2004, Morrissey has had a weekend talk radio show in the Minneapolis/St. Paul area and often fills in as a guest on Salem Radio Network's nationally-syndicated shows. He lives in the Twin Cities area of Minnesota with his wife, son and daughter-in-law, and his two granddaughters. Morrissey's new book, GOING RED, will be published by Crown Forum on April 5, 2016.

-

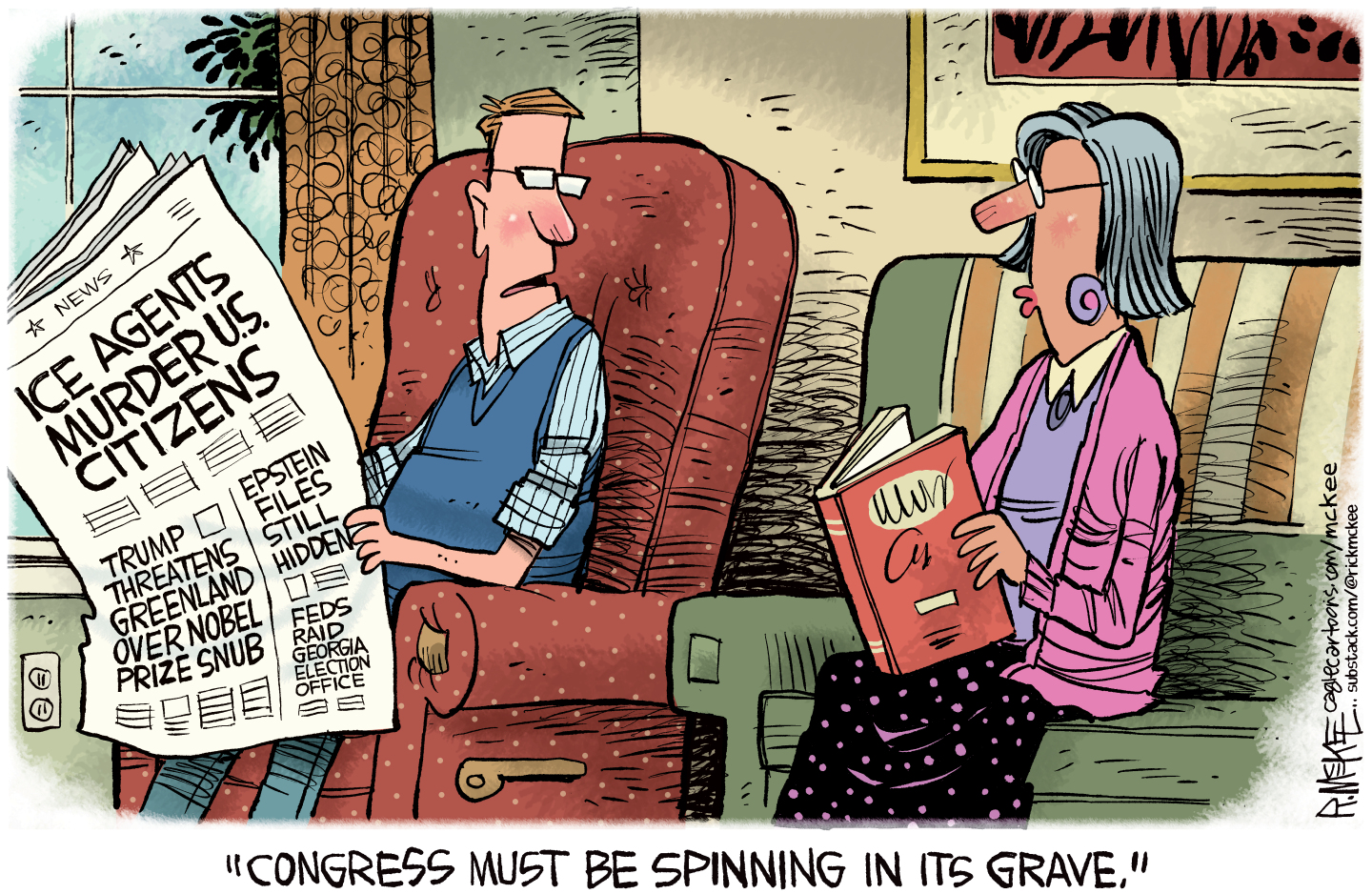

Political cartoons for January 31

Political cartoons for January 31Cartoons Saturday's political cartoons include congressional spin, Obamacare subsidies, and more

-

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US ally

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US allyTalking Point Ahmed al-Sharaa’s lightning offensive against Syrian Kurdistan belies his promise to respect the country’s ethnic minorities

-

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?Talking Point Rambling speeches, wind turbine obsession, and an ‘unhinged’ letter to Norway’s prime minister have caused concern whether the rest of his term is ‘sustainable’

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred