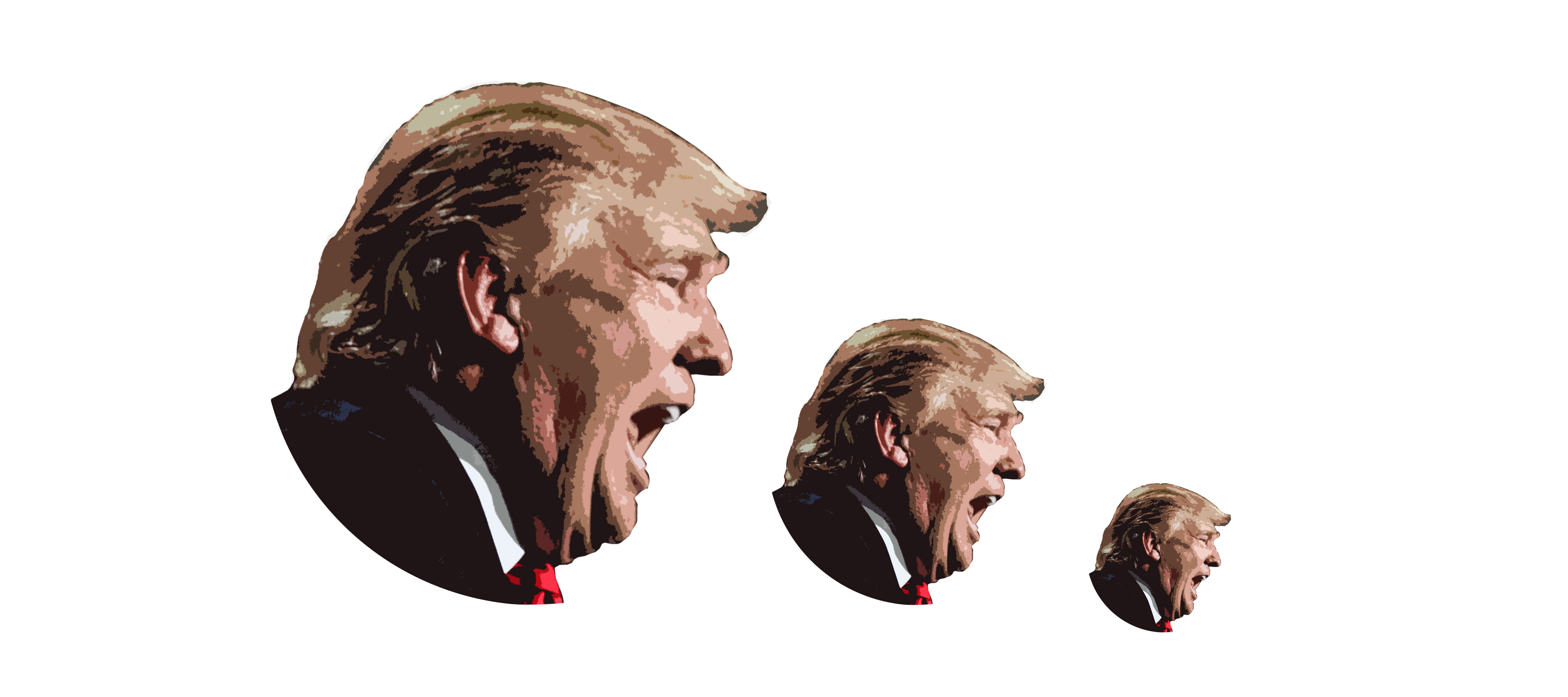

How Trump trumped trump

America's president, destroyer of words

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A few weeks ago, I had a conversation with my brother about trump. You know, the regular old word with a lowercase t, the one unrelated to America's president — or at least, the one that used to be.

Until relatively recently, trump pretty much still meant, as a verb, "to get the better of," particularly in a card game, or to have in one's possession the card that guaranteed the win, either literally or metaphorically. It's a word that most people didn't use all that often, but when they did, they didn't tend to think first and foremost about an orange-hued man named Donald.

Everything is different now. When I tweeted about this exchange with my brother, the responses varied from the empathetic ("It has gotten hard to play certain card games since November") to the optimistic ("Just be thankful his last name isn't Love, or Cake"). Yet not a single person said anything to defend the use of trump; trump, as we knew it, was over.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Along with everything else the election hath wrought, some of the less obvious casualties have been things I never thought I'd lose, like the ability to enjoy purely silly frivolity, or, say, use words without fearing their meanings have been co-opted by another force. But it shouldn't be surprising that our new president — whose entire mode of PR, even now, is to make us so fully aware of him in every context, every facet, every pore that we simply can't be unaware — has had such a rapid impact on our language. In October, Robinson Meyer wrote a piece for The Atlantic titled "Another victim of this election: The verb 'to trump.'" In it, he predicted that Trump's "campaign will doom a perfectly pleasant word, a happy verb with a 750-year history. That is, even after the election ends, speakers and writers of English might dump the verb to trump."

Since then, several buildings in New York City have removed the name from their facades. If the word splashed on a sign can't be trusted to convey what developers would like it to mean, how can anyone feel confident parlaying it casually across a dinner table? Certainly, contexts change and words do too, picking up new and revised meanings as they course across tongues and over time. But trump seems a special case. How did this shift happen so rapidly?

"It's not uncommon for us to become reluctant to say a perfectly good word," explains Katherine Connor Martin, head of U.S. Dictionaries at Oxford University Press. Martin recalls the example of "niggardly," a word that means "stingy." In 1999, a top aide of then-D.C. Mayor Anthony A. Williams resigned after coming under fire for using the word to describe how he'd manage a tight budget. (He was eventually rehired.) "Even though that word is not in any way related to the racial slur, it was regarded as offensive," Martin says. There are plenty of other words you'd probably avoid saying, because "why would you go down that road? ... There's a vegetable that can be called 'rape' or 'rabe' or 'rapini.' You'll probably go with 'rabe' or 'rapini.'"

And sometimes, the meaning of a word changes entirely. For instance, Martin notes, "We don't say 'bitch' very lightly for a dog, even though there's nothing wrong with it."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

When it comes to presidents, George W. Bush brought forth plenty of emotions, but he didn't cause us to clamp our hands to our mouths whenever we passed an innocent plant or called the gardener. What's with Trump trumping trump, then? Well, trump is a less common word to start, "less mapped in people's heads." It's also a less core concept; the use of "trump card" is largely figurative, and we have other ways to get across that same meaning. With Bush, perhaps the vitality of the word in our language, used to indicate a basic and identifiable object, meant that the person could also exist, unrelated, even, to the word in question (he's not the only one with a noun as a last name). But with Trump, the person and the word seem to have convened — even if it's a hugely ironic merger ("a dependable and exemplary person"?).

"There are these resonances between the playing-card association and Trump's desired brand, his concept of 'winning,'" Martin says, referring to the John Oliver bit in which the comedian argues we should use Trump's ancestral name and call him "Drumpf" instead of the word so many associate with power and money. "My instinct is that even though there might be a stronger passion now than with George W. Bush, it's fundamentally about the strength of the core meaning of the word, and the distance of the core meaning of the word from the concepts you associate with the person," she explains. "With trump, you have a less strong core concept and you have a closer relationship between the word and the person."

Of course, there are other meanings of trump. "Trumpet," for instance. The slang meaning from the 1900s, "the act of breaking wind audibly," which is still used in the U.K. In an obsolete meaning, "a thing of small value, a trifle" (very small fingers, maybe?). Or, "to deceive, cheat." There's even "to impose or thrust (something) upon a person," a meaning that's far too real for quite a lot of reasons.

Could trump change yet again? Yes, says Martin: "We can 'verb' anything, and people's names are frequently verbed" — including that of Captain Charles Boycott, who did exactly what you think. Lexicographically, a new trump would be a different word, etymologically distinct, "but it's not impossible that there would be a verb that would be associated with Donald Trump, meaning, say, 'to unexpectedly win an election.' For instance, he 'trumped the Senate race.' It could displace the other uses." Or, "it could be a 'bitch' scenario," Martin says. (I can't help laughing, maybe silly frivolities will survive after all.) "The only thing I can say with certainty is it's impossible to predict. It's just as possible the association will make us use it more instead of less."

Of course, if the essential purpose of any conversation is to get your point across without distraction, we're inherently partial to words that don't have multiple, incendiary other meanings and interpretations. So, for the moment, in my non-lexicographer view, the word is a goner. Until we turn it around and make it something else. Words, like politics, have a way of surprising you.

Jen Doll is the author of the memoir Save the Date: The Occasional Mortifications of a Serial Wedding Guest. She's also the managing editor for Mental Floss magazine and has written for The Atlantic, Esquire, Glamour, Marie Claire, The Hairpin, New York magazine, The New Republic, The New York Times Book Review The Village Voice, and other publications.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred