How does impeachment work?

With scandals swirling around the White House, the 'I-word' is already being mentioned in Congress

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

With scandals swirling around the White House, the 'I-word' is already being mentioned in Congress. Here’s everything you need to know:

Has any president been impeached?

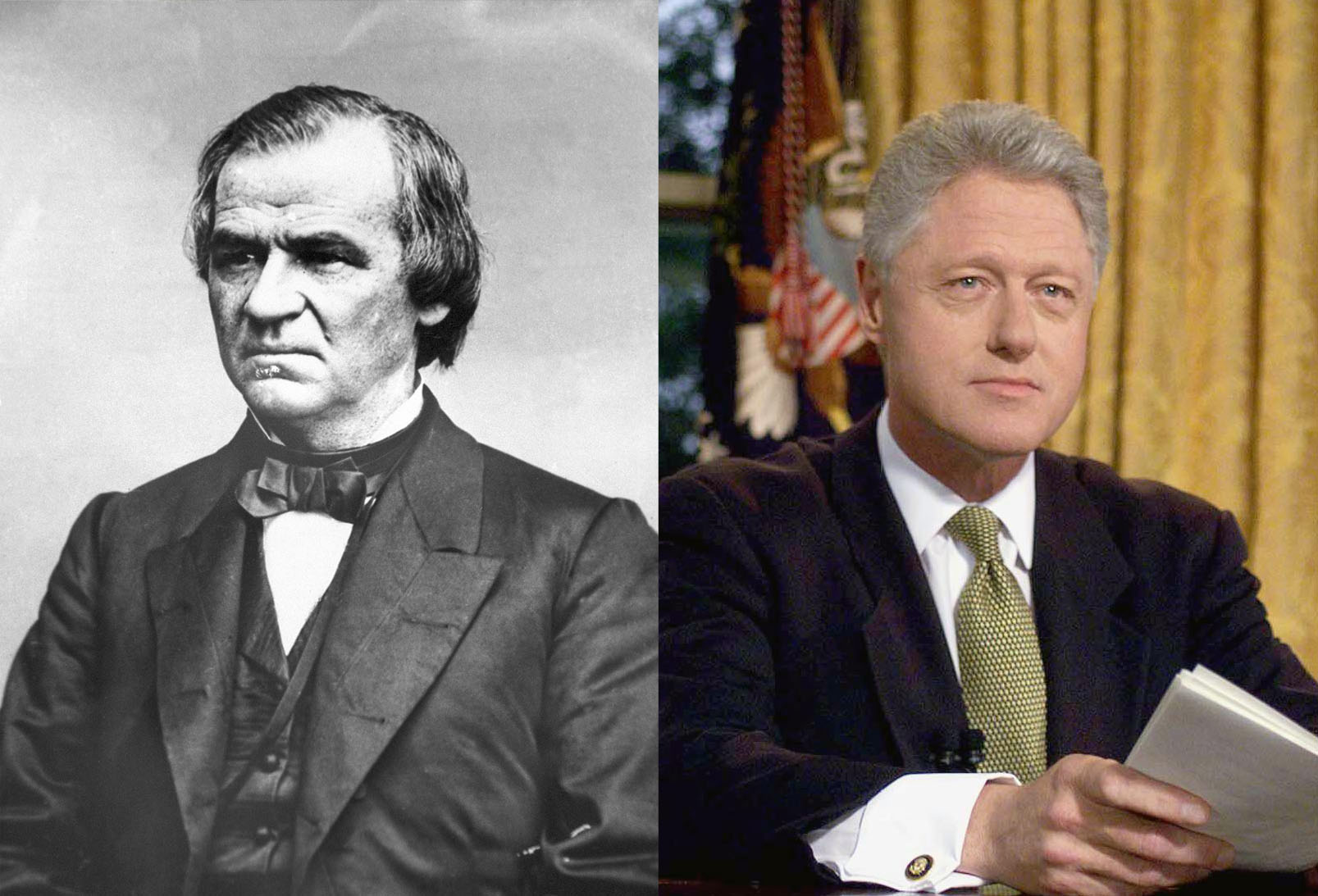

Only two presidents have ever been impeached by the House, and both were acquitted by the Senate. Andrew Johnson was targeted in 1868 because of a power struggle over policy in the post–Civil War South; Bill Clinton, in 1998, over his affair with White House intern Monica Lewinsky. Richard Nixon faced impeachment, but quit first. (See below.) Impeachment chatter is rife again following the appointment of a special counsel to investigate potential collusion between President Trump's campaign and Russia, and Trump's legal team has reportedly begun researching how to defend him if he's impeached. The odds of Trump being impeached before the end of his first term have risen to 60 percent, according to betting house Paddy Power, and at least 26 Democrats and two Republicans have dropped the I-word. But the impeachment process is long, complicated, and heavily influenced by partisan considerations. If it happens, says Bill McCollum, a former Republican member of Congress who voted to impeach Clinton, "it's not going to happen overnight."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Where did impeachment originate?

The process dates back to 14th-century England, where it was used to prosecute lords and royal advisers who were beyond the reach of the courts. The framers of the U.S. Constitution — mindful of the possibility of tyranny — borrowed that concept for our founding document as a peaceful way of removing rogue presidents, as well as vice presidents, Cabinet secretaries, federal judges, and Supreme Court justices. There was vigorous debate over whether to give the power to impeach to the Supreme Court, but in the end, the Constitution gave the House of Representatives the "sole Power of Impeachment," and the Senate "sole Power to try all Impeachments" — that is, to decide whether to convict or acquit.

What are impeachable offenses?

"Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors," according to the Constitution. But the definition of "high crimes and misdemeanors" remains highly contentious. Some constitutional scholars believe the term should apply only to a violation of written law; others argue it applies to any abuse of power or behavior that demeans the presidency. In practice, the interpretation is almost entirely political. Clinton was impeached for perjury and obstruction of justice because he'd lied under oath in testimony before a grand jury and in a deposition about whether he'd had an affair with Lewinsky. During impeachment proceedings, press reports revealed that several Republican leaders were guilty of their own adulteries, but they argued — unsuccessfully — that it was the lying, not the affair, that most mattered. In reality, quipped then–House Minority Leader Gerald Ford in 1970, "an impeachable offense is whatever a majority of the House of Representatives considers it to be at a given moment in history."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

How does the process work?

First, the House must vote by a simple majority for impeachment proceedings to begin. Any member of the House can introduce a resolution to do so, as can a committee, a petition, a special prosecutor, or the president. If a simple majority approves one or more articles of impeachment, the president has officially been impeached — a process similar to indictment. It is then up to the Senate to hold a trial.

How does the trial proceed?

The House designates certain representatives, known as "managers," to serve as prosecutors and argue the case for conviction. The president selects lawyers to serve as a defense team. The senators serve as the jury, presided over by the chief justice of the Supreme Court — though senators also get to determine certain procedural rules, such as whether to hear live-witness testimony. "Impeachment is a creature unto itself," says former Rep. Bob Barr, one of the House managers during Clinton's trial. "The jury in a criminal case doesn't set the rules for a case and can't decide what evidence they want to see and what they don't." There is also no defined standard of proof; the bar for conviction is whatever each senator wants it to be. If more than two-thirds of senators find him guilty, the president is removed from office — and the vice president takes his place.

Could Trump be impeached?

The ongoing investigation by special counsel Robert Mueller certainly raises that possibility. Rep. Al Green (D-Texas) says he has already begun drafting his own articles of impeachment, arguing that Trump is guilty of obstruction of justice for allegedly pressuring then–FBI Director James Comey to drop his investigation into possible collusion between Trump's team and the Kremlin, and then firing Comey in hopes of ending that probe. Clinton and Nixon were both cornered over obstruction of justice; but unlike Trump, they faced a hostile Congress controlled by the opposition party. For Republicans to turn against their own president and provide the votes to impeach him, Trump's approval ratings would have to tank to the point where he represented a liability for the entire party. "Ninety-nine percent of the game," says former Justice Department official Bruce Fein, "is how popular is the president."

Nixon's almost-impeachment

Richard M. Nixon was implicated in the biggest political scandal of the 20th century: Watergate. The evidence against him was so damning that he would almost certainly have been impeached and convicted, but he managed to avoid that indignity by resigning. The House Judiciary Committee in July 1974 had already approved three articles of impeachment against "Tricky Dick" for obstruction of justice, abuse of power, and contempt of Congress involving the break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in 1972. Six days later, a "smoking gun" tape emerged proving Nixon had authorized the Watergate cover-up from the beginning. When Republican leaders told him he'd lost most of his support in the House and Senate, Nixon decided to resign. "There is no longer a need for the process to be prolonged," he said in a dramatic speech. A month later, he was pardoned by his former vice president and successor, Gerald Ford, for any and all crimes he may have committed. Nixon, said Ford, had "suffered enough."

-

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’Feature An office doormat is stranded alone with her awful boss and a frazzled therapist turns amateur murder investigator

-

Movies to watch in February

Movies to watch in Februarythe week recommends Time travelers, multiverse hoppers and an Iraqi parable highlight this month’s offerings during the depths of winter

-

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance iceberg

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance icebergIN THE SPOTLIGHT Federal troops are increasingly turning to high-tech tracking tools that push the boundaries of personal privacy

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred