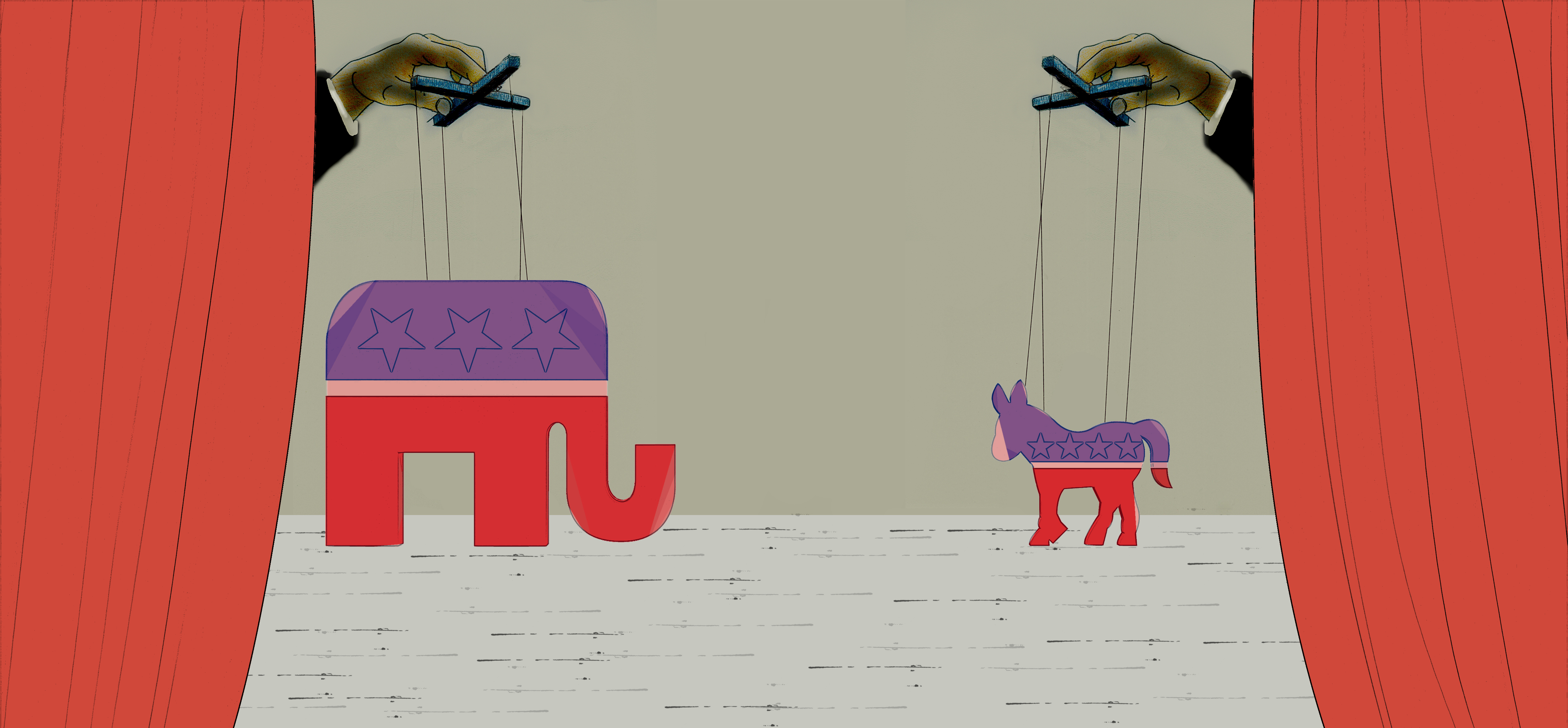

Virginia was a huge victory for Democrats. But it also shows how elections are rigged in Republicans' favor.

Here's how Republicans win — even when they lose

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Tuesday's election in Virginia was a stunning victory for Democrats. Their governor candidate, Ralph Northam, won by 9 percentage points, after polls showed his lead shrinking to 3 or so in the race's final days. They also won the other two statewide races, for lieutenant governor and attorney general. And they cut deeply into the Republicans' advantage in the House of Delegates, winning three open seats and taking out at least 13 incumbents. With recounts in a number of races underway, it's entirely possible they could seize control of the chamber for the first time in two decades.

That looks like a triumph, and it is. But it also demonstrates in one state just how much the game of elections is rigged in Republicans' favor.

Why is that? Consider the mountain Democrats had to climb in order to even have a chance at controlling the state legislature. Virginia is a swing state, but one that has turned decisively blue, particularly since the more diverse urban and suburban areas of the state (like the Washington suburbs in the north) have been growing much more rapidly than the rural areas of the state where Republicans dominate. The last three Democratic presidential candidates won Virginia, and both the state's senators are Democrats as well. Yet before Tuesday, not only did Republicans enjoy a narrow 21-19 advantage in the state senate, they controlled two-thirds of the seats in the House of Delegates, holding the chamber by a 66-34 margin.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Democrats might manage to take control of the House of Delegates once the counting and recounting is done. But when you add up all the votes cast, you find that Democratic candidates won 54.7 percent of the two-party vote, while Republican candidates won only 45.3 percent. Yet Republicans may well retain control despite having lost the popular vote by such a significant margin.

That's an affront to majority rule, yet it's repeated in state after state and at the federal level — again and again to the benefit of Republicans. It has partly to do with the fact that Republican voters are spread around more efficiently, while Democrats are often concentrated in cities, in effect "wasting" votes (if you win a race 95-5, you've used up a lot of votes that could have been more advantageously deployed elsewhere). But it's also because Republicans successfully gerrymander districts to maximize their advantage. Because Republicans had a great election in 2010, they were in control in many places for the redistricting that takes place every decade once the Census is complete, and they didn't let the opportunity to redraw the lines pass by. While there are a few states where Democrats have been as ruthless at gerrymandering as Republicans, it's something Republicans are particularly aggressive about.

That's just one of the advantages the GOP enjoys, some of which are built into the system. The United States Senate is constructed on a foundation of inequality, giving outsize power to small, rural states at the expense of states with large metropolitan areas. Wyoming's 585,000 souls get the same two votes in the Senate as California's 39 million — or 67 times as much voting power per person. It's likely to get even worse in the future as the most populous states continue to grow faster than rural states.

The Republican small-state advantage then translates into a boost in the Electoral College, since each state gets as many electoral votes as they have members in the Senate and the House. That's why in two of the last five presidential elections, the Democrat got more votes but the Republican wound up in the Oval Office.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

It's entirely possible that in 2018, we'll see a situation in the House of Representatives much like what's happening in Virginia now, in which Democrats would win a majority of votes for Congress but still find themselves in the minority. It has happened before: In 2012, Democrats won more votes for House seats nationally than Republicans, but the GOP still held on to a comfortable 33-seat advantage. Most analysts assume that for Democrats to take back the House, they'd need to not just outpoll Republicans but win by a significant margin.

In other words, Republicans win when they win, and sometimes even when they lose. Democrats, on the other hand, often have to put together a landslide to win.

And that's not even to mention the aggressive campaign of vote suppression Republicans have undertaken, passing laws to make voting more difficult and cumbersome in the hopes that populations more likely to vote for Democrats, particularly African-Americans, will be discouraged from voting (in one recent case about a North Carolina vote suppression law, the judges who struck it down wrote that the law's provisions "target African Americans with almost surgical precision"). They've pushed vote suppression as far as they can, and there's a good chance that the conservative-dominated Supreme Court will let them get away with it.

The big picture is that Republicans enter every election with some built-in advantages, and then when they get power, they alter the system to exaggerate those advantages and tilt the playing field even more in their direction. Democrats can overcome it, just as someone wearing ankle weights might be able to win a race against opponents not so encumbered. But that doesn't mean it was fair.

Paul Waldman is a senior writer with The American Prospect magazine and a blogger for The Washington Post. His writing has appeared in dozens of newspapers, magazines, and web sites, and he is the author or co-author of four books on media and politics.

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred