America's outrage over Russian election meddling is a blatant double standard

If Putin's mischief-making constituted an act of war, then the U.S. has committed acts of war against an astonishingly long list of countries

The extent to which the presidential campaign of Donald Trump was aware of (and perhaps even colluded with) the Russian government to interfere with the 2016 election remains uncertain. But that the Russian government did interfere with the 2016 election is not.

That became clearer than ever last Friday, when the Justice Department announced the indictment of 13 Russian nationals and three companies, charging them with stealing the identities of American citizens, posing as activists, and working in a multitude of ways to manipulate the outcome of the vote.

But what exactly was the government of Russian President Vladimir Putin attempting to achieve with its meddling? And what is the proper American response?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

On these questions, pundits writing from the supposedly sensible ideological center of American politics appear to agree: Putin wanted to elect Trump, and his (shockingly successful) effort may well have constituted an act of war. Some, like foreign policy analyst Max Boot and New York Times columnist Tom Friedman, even go so far as to imply that President Trump is a traitor for failing to retaliate — a shirking of responsibility equivalent in its gravity to an imagined George W. Bush shrugging his shoulders in indifference following the 9/11 attack.

Such claims may come from the center, but they are anything but sensible.

Of course we don't want Russia meddling in our elections. And yes, we absolutely should be working to protect ourselves against such interference in the future. But if Putin's mischief-making constituted an act of war against the United States, then the U.S. has committed acts of war against an astonishingly long list of countries since the end of World War II. One study estimates that we interfered with no fewer than 81 elections in 45 nations from 1946 to 2000. Such efforts have been so brazen and uncontroversial that former CIA Director James Woolsey recently felt comfortable laughing about them with Laura Ingraham on Fox News.

This doesn't mean that we should respond to Putin's program of manipulation with indifference. Far from it. But it does mean that a response of self-righteous indignation is risible. To treat such meddling as an act of war on the part of Russia is either to invoke a blatant double standard that permits the U.S. to do things we stridently denounce in others — or it's to admit that our own actions have been far more pernicious than we like to think. We definitely need to protect the integrity of our elections, but we should do so without placing ourselves unconvincingly on the moral high ground.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The second and more serious problem with the "act of war" line is that it grows out of a misperception of what Russia was really trying to accomplish in its meddling. Those who stake out the most strident position on Russian electoral interference often emphasize that Putin wanted Trump to prevail — and that he succeeded, ending up with a Manchurian Candidate in the Oval Office.

Between Clinton and Trump, Putin undoubtedly preferred Trump — among other reasons because he had every reason to expect that a Trump administration would be less geopolitically confrontational than a Clinton one. Yet Putin's aims went far beyond attempting to manipulate the precise outcome of the vote in one way or the other. We know this because of the range of positions that the indicted individuals and companies endorsed in their online interventions. They defended Trump, yes, but they also attacked him, and attacked Clinton, while both championing and denouncing Black Lives Matter, and defending Bernie Sanders and Jill Stein.

The goal wasn't so much to elect one candidate over another. It was to intensify pre-existing polarization in American political culture, thereby provoking chaos as well as (in the words of journalist Julian Sanchez) sowing "doubt about the integrity and fairness of American elections." As I argued in a column nearly a year ago, Putin's calling card isn't the standard totalitarian (communist or fascist) approach of pushing one propagandistic line ("Elect Trump!"). Putin's approach to electoral manipulation is far more postmodern: the effort to inspire confusion, doubt, suspicion, and despair in the electorate about the possibility of ever finding a truth that everyone can affirm.

In an illuminating podcast I quoted in that old column, author Anne Applebaum explained how Putin's government deployed this technique after a mysterious explosion brought down a passenger jet over Ukraine in July 2014. Instead of pushing a single false account of what destroyed the plane, Russia attempted to "pollute the information space" by spreading a huge number of contradictory accounts of what might have happened, some of them plausible, others of them completely fanciful.

Tell a multitude of lies — and stir the pot of ideological disagreement and divisiveness in the country — and eventually people won't know what to believe. And once people have given up trying to tell truth from falsehood, or "my tribe's truth" from truth in itself, a petty dictator can get away with pretty much anything he wants.

That sounds downright dangerous — and it certainly is. But it would be ridiculous to blame Putin for it. Russia undoubtedly contributed (and still contributes) in some small way to the trend, but in the run-up to the election we were doing a remarkably good job of trolling ourselves all on our own. And it's gotten far worse since then — as we see all too clearly every single day on Twitter, and in the highly polarized response to the Russian investigation itself.

Putin pushed us a bit further in the direction we were already headed. That's bad, but not nearly as bad as some would have us believe — and nowhere near as troubling as taking an honest look in the mirror.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

A running list of US interventions in Latin America and the Caribbean after World War II

A running list of US interventions in Latin America and the Caribbean after World War IIin depth Nicolás Maduro isn’t the first regional leader to be toppled directly or indirectly by the US

-

How to rekindle a reading habit

How to rekindle a reading habitThe Week Recommends Fall in love with reading again, or start a brand new relationship with it

-

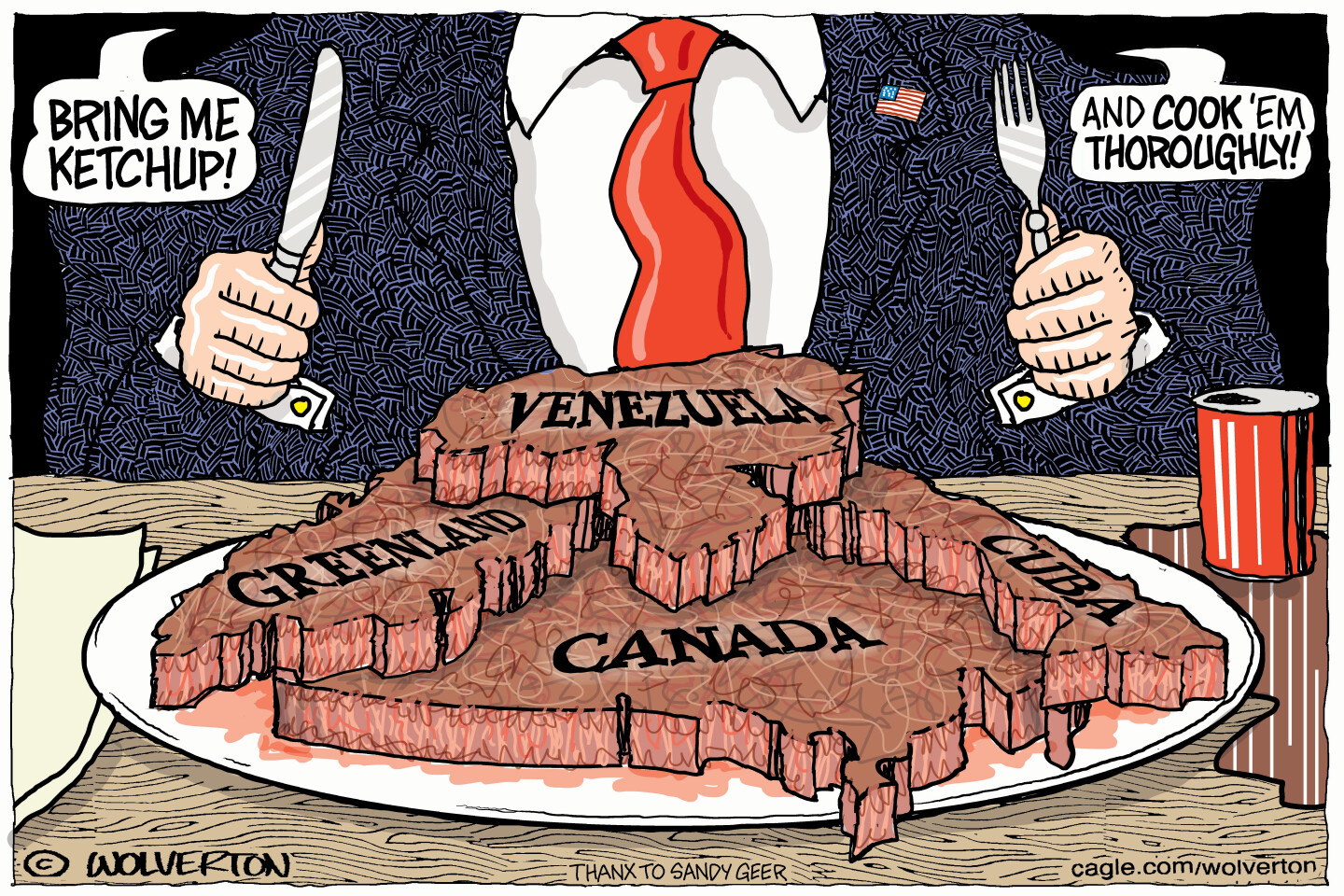

Political cartoons for January 8

Political cartoons for January 8Cartoons Thursday’s political cartoons include a well-done steak, a silenced protester, and more

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred