Why aren't wages growing faster?

Perhaps the economy still isn't as hot as you think

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

At first blush, America got a doozy of a jobs report last week. Employment jumped by 313,000, its biggest single-month gain since mid-2016. But there also was some attendant weirdness: The unemployment rate didn't budge, and, worse, wage growth actually slowed down.

That dip in wages, in particular, reveals a lot about America's economy.

You might remember last month when it was reported that wages had grown 2.9 percent between January 2017 and January 2018. That was higher than expected. Financial markets became convinced that inflation was right around the corner, and the Federal Reserve would have to raise interest rates faster than anticipated. The result was a good-news-is-bad-news panic that sent the stock market into a series of spectacular plunges.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

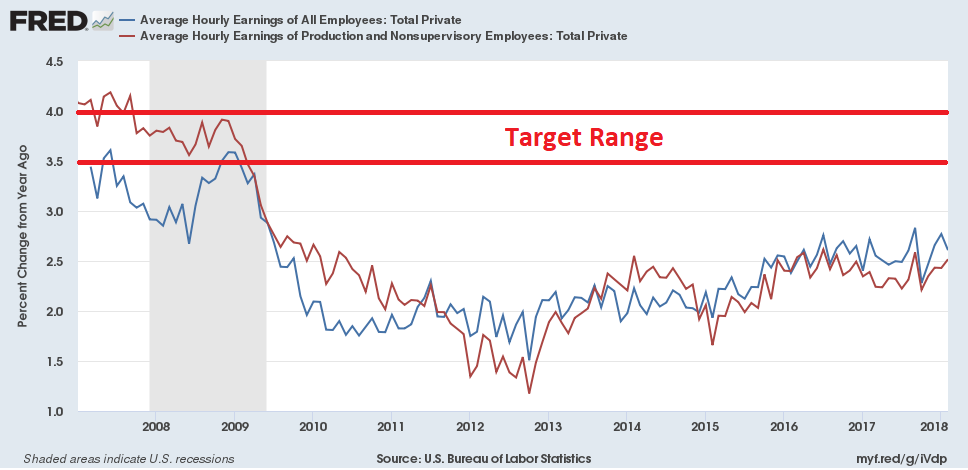

At the time, I argued this was probably a blip: Other economic fundamentals didn't justify inflation worries. Sure enough, January's change was later revised down, and February's year-over-year growth fell to 2.6 percent. We're right back on the lackluster trend that's characterized the entire recovery from the Great Recession, under both Presidents Obama and Trump. And we're still well below the 3.5-to-4 percent wage growth that's usually associated with full employment or something close to it.

That in and of itself is weird.

Unemployment is at 4.1 percent, which is already lower than it was in 2007, and almost as low as it was in 2000 — the last two times we achieved 4 percent wage growth. Remember, labor scarcity is what increases pay. As unemployment falls, there are fewer workers just waiting around for jobs, so companies have to raise their offers to poach already employed workers. That, in turn, can lead to higher prices for things and thus inflation. With unemployment where it is, wage growth shouldn't be this low.

It gets weirder.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Let's return to the unemployment rate for a moment. It's been at 4.1 percent for several months now, and February saw little change. How do you add 313,000 new jobs to the economy without the unemployment rate so much as twitching?

Part of the answer is that new workers are constantly joining the economy as young people come of age and immigrants arrive. That will continue so long as the population keeps growing.

But this is a pretty extreme discrepancy to be explained by that alone. The answer is likely elsewhere in last week's jobs report: Labor force participation jumped from 62.7 percent to 63 percent. That's an increase of 806,000 people.

The unemployment rate is a percentage, but a percentage of what? It would be silly to count stay-at-home parents or retirees as “unemployed.” The answer is it's a percentage of the labor force — everyone who either has a job, or has looked for one in the last month. The assumption is that if people are looking for work more sporadically than that, they probably have good reason to be out of the workforce, and shouldn't be counted as “unemployed” by government statistics.

But that assumption could be wrong. Indeed, the leading theory for why wage growth remains so sluggish is that it is wrong.

If the economy gets hit by a big enough crisis that cripples the job market for long enough, people could get so discouraged from looking for work, they just give up.

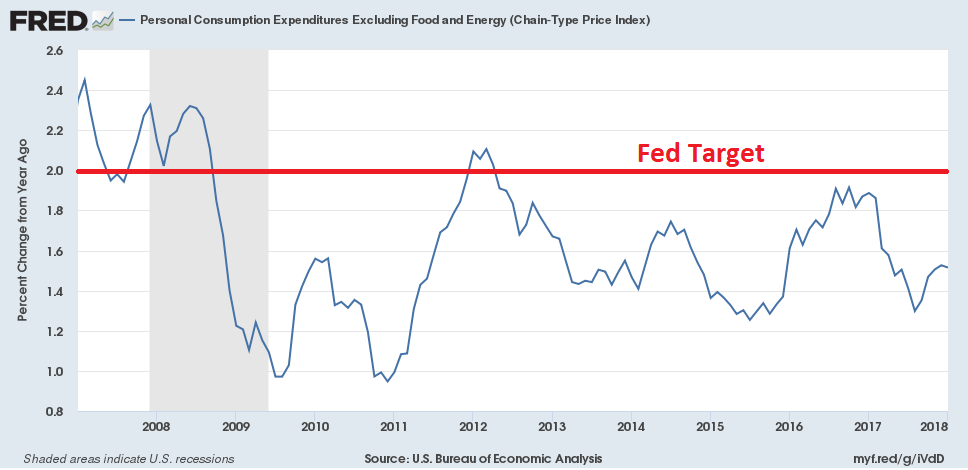

After the Great Recession, labor force participation collapsed, from 66 percent of all American adults to the current 63 percent. Retirements and the growing elderly share of the population cannot explain this drop by itself. There's also an economic rule of thumb called the Phillips Curve: tell an economist where unemployment is, and the Phillips Curve then tells them where inflation should be. But since the Great Recession, that relationship has broken down. Despite the low unemployment rate, inflation refuses to rise to the Federal Reserve's 2 percent target.

Now we have February's job report, which added 313,000 jobs without lowering the unemployment rate. But labor force participation did increase. In other words, those 313,000 new jobs weren't just filled by young people, or people drawn from the officially unemployed. They were drawn from people who were out of the labor force entirely.

This can explain the wage mystery. If many people still out of the labor force are actually potential workers — and there may be many millions of them — then labor is not as scarce as we think. That means we're also not as close to maxing out employment as we think. In which case sluggish wage growth makes perfect sense.

Alternatively, we can ignore the labor force entirely, and just concentrate on all Americans in their prime working years (ages 25 to 54). The percentage of that population with a job only recently grew above its lowest point in the 2001 recession. In fact, if you rerun the Phillips Curve but link inflation to the prime age employment ratio rather than to unemployment, the discrepancy goes away.

The good news is we're headed in the right direction. We keep adding jobs. Wage growth has grown since it bottomed out after 2008. The prime age employment ratio is heading up. The next thing to look for will be a sustained rise in labor force participation.

The economy is healing. It's just that its wounds were deeper than we thought.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

Democrats push for ICE accountability

Democrats push for ICE accountabilityFeature U.S. citizens shot and violently detained by immigration agents testify at Capitol Hill hearing

-

The price of sporting glory

The price of sporting gloryFeature The Milan-Cortina Winter Olympics kicked off this week. Will Italy regret playing host?

-

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?Feature Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard is Trump's de facto ‘voter fraud’ czar

-

The pros and cons of noncompete agreements

The pros and cons of noncompete agreementsThe Explainer The FTC wants to ban companies from binding their employees with noncompete agreements. Who would this benefit, and who would it hurt?

-

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contraction

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contractionThe Explainer The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

-

The death of cities was greatly exaggerated

The death of cities was greatly exaggeratedThe Explainer Why the pandemic predictions about urban flight were wrong

-

The housing crisis is here

The housing crisis is hereThe Explainer As the pandemic takes its toll, renters face eviction even as buyers are bidding higher

-

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkers

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkersThe Explainer Show up for your colleagues by showing that you see them and their struggles

-

What the stock market knows

What the stock market knowsThe Explainer Publicly traded companies are going to wallop small businesses

-

Can the government save small businesses?

Can the government save small businesses?The Explainer Many are fighting for a fair share of the coronavirus rescue package

-

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shock

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shockThe Explainer This could be a huge problem for the entire economy