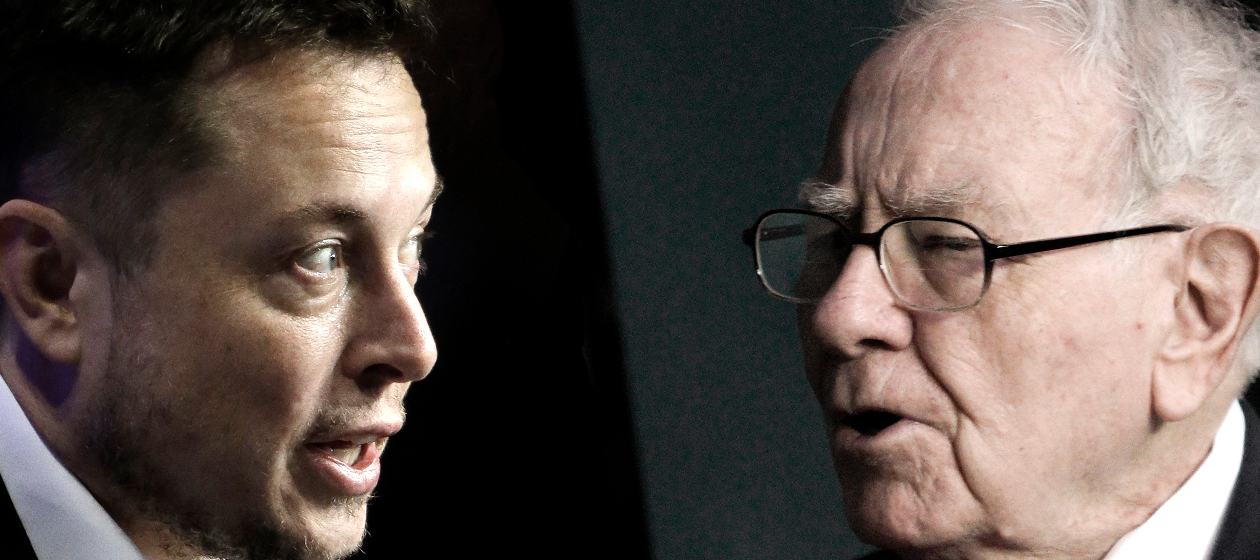

Elon Musk and Warren Buffett are fighting about moats and candy. This is serious.

No really. It is!

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Elon Musk and Warren Buffett are fighting over moats and candy. And strange as that may sound, there's a lesson about American innovation and investment hiding in the kerfuffle.

The tetchy back-and-forth began last week. Following Tesla's earnings report, Musk did his duty as CEO and took a conference call with analysts. He got remarkably cantankerous. Tesla's latest electric car model is giving the company headaches, and it's burning through cash very quickly. An annoyed Musk spent much of the call swatting down legitimate questions as "boneheaded" and "dry."

Then the subject of "moats" came up. This was a reference to an old bit of wisdom from Buffett, CEO of the mega-conglomerate Berkshire Hathaway and one of the grand old men of American investors. Moats, according to Buffett, are advantages that make it hard for a company to be overtaken by competitors: things like established distribution networks, recognizable brands, and market power.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"I think moats are lame," Musk said on the call. "They're like nice in a sort of quaint, vestigial way. But if your only defense against invading armies is a moat, you will not last long. What matters is the pace of innovation. That is the fundamental determinant of competitiveness."

Buffett was none too pleased.

"There are some pretty good moats around," Buffett shot back on Saturday. "Elon may turn things upside down in some areas, [but] I don’t think he’d want to take us on in candy." Buffett meant See's Candies, which Berkshire purchased in 1972, and whose sales have grown ten-fold since. It has quite a moat in the sweets business.

Not to be outdone, Musk tweeted that he's "starting a candy company & it’s going to be amazing." He added: "I am super super serious."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Granted, this whole thing is kind of funny. And Musk's last potshot in particular seems tongue in cheek. But there are also some (super super) serious threads worth untangling here.

For many investors, Buffet's pro-moat advice seems good. Reliable moats mean reliable profits, and those mean reliable returns. It's certainly alluring to think you could invest in the next successful conquest of an existing American businesses. But you're probably better off giving up the dream of an enormous payday, and instead settling for a stream of reliable payouts.

But look at it from Musk's point of view. The United States suffers from a paucity of risk-taking and innovation. The economy is increasingly dominated by a smaller number of massive, older firms. New competitors are often gobbled up by established players before they can get big. A bit more swashbuckling willingness to storm the moats might seem like just what the economy needs.

Sadly, neither of these strategies will do all that much to fix our economy and really help lower- and middle-class Americans.

While 54 percent of Americans invest in the market in one way or another, all too many millions more are left out. And even of those with investments, many have relatively paltry holdings. Moats or no moats, these Americans are left outside the castle walls.

After all, America's trend toward bigness and concentration has continued right through the moat-hopping tech revolution that Musk represents. Even when they successfully overturn the old order, Silicon Valley giants like Google and Facebook do not level the playing field; they simply become the new monopolies.

Faced with a drought of productivity, we easily fall into a "great man theory" of innovation. We try to reinvigorate the American economy by unshackling its capitalist geniuses. But we've been deregulating and tax-cutting our way to an unbound entrepreneurial class for decades now. The results for growth, wages, and livelihoods have been underwhelming, to put it mildly.

Wall Street's relationship to the rest of the economy is basically parasitical. If they want, investors can just sit back and bleed the rest of us dry. No wonder moats look attractive to some of them.

Ultimately, it's probably better when risks are taken by people who temperamentally avoid them: When we use policy structures to force old-fashioned business leaders to innovate — rather than leave risk-taking to the people who get an ego-driven thrill from it.

"Saying you like 'moats' is just a nice way of saying you like oligopolies," Musk huffed at one point in the dispute. That's certainly true. But that doesn't mean the answer to oligopolies is more people like Elon Musk.

In its heyday, American productivity was not the result of a few capitalist titans. It was a collective project that all of society shared in. It worked because we'd put in place rules that made it work. Then we let ourselves get talked into ditching the rules.

The problem with Buffett and Musk's spat is that, no matter which side you support, most Americans lose. Maybe the escape from that trap lies in a return to the old ways.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The pros and cons of noncompete agreements

The pros and cons of noncompete agreementsThe Explainer The FTC wants to ban companies from binding their employees with noncompete agreements. Who would this benefit, and who would it hurt?

-

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contraction

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contractionThe Explainer The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

-

The death of cities was greatly exaggerated

The death of cities was greatly exaggeratedThe Explainer Why the pandemic predictions about urban flight were wrong

-

The housing crisis is here

The housing crisis is hereThe Explainer As the pandemic takes its toll, renters face eviction even as buyers are bidding higher

-

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkers

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkersThe Explainer Show up for your colleagues by showing that you see them and their struggles

-

What the stock market knows

What the stock market knowsThe Explainer Publicly traded companies are going to wallop small businesses

-

Can the government save small businesses?

Can the government save small businesses?The Explainer Many are fighting for a fair share of the coronavirus rescue package

-

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shock

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shockThe Explainer This could be a huge problem for the entire economy