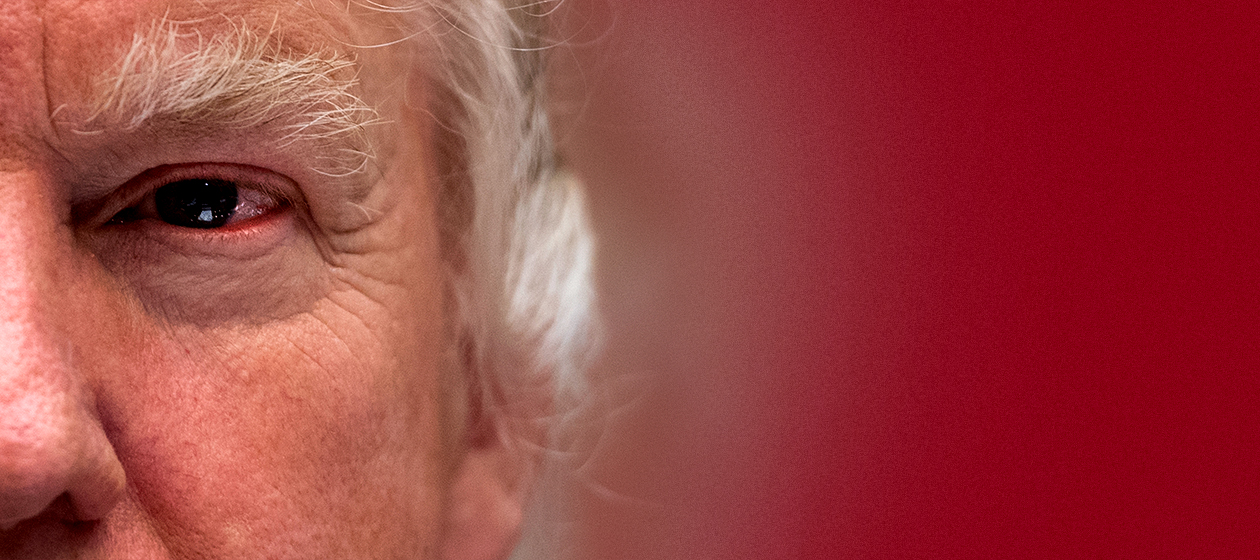

The art of the threat

In conflicts at home and abroad, Trump's strategy is always the same

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

This is the editor’s letter in the current issue of The Week magazine.

Niccolò Machiavelli, that jaundiced student of human nature, pointed out in 1517 that sometimes "it is a very wise thing to simulate madness." I suspect President Trump has not read the Discourses on Livy, but he instinctively practices what Machiavelli preached. Richard Nixon called this approach "The Madman Theory" of foreign policy: Make your adversaries think you're so rabid, so unhinged, that you're capable of anything, including launching the ICBMs. Our current president has used precisely that message in his dealings with North Korea and Iran, but he's taken the "madman" strategy to a new level. When allies and adversaries at home or abroad fail to bend to his will, Trump invariably goes nuclear. He's threatening to impose a 25 percent tariff on foreign cars and auto parts, and slap other massive penalties, on China, Europe, and the U.S.'s NAFTA partners; he's yanking children from parents to discourage asylum seekers who show up with children at the border; he keeps warning he'll put an end to the Russia investigation if investigators go "too far."

History may credit Trump for creating the Grand Unified Madman Theory: In all conflict and negotiations, act as if you don't care who gets hurt or what gets wrecked. Is it working? It's a bit early to say. We don't yet know whether Kim Jong Un wants a summit because he fears Trump — or believes a needy and impulsive president can be manipulated. China, Canada, and Mexico have yet to yield to Trump's theatrical trade demands. Special Counsel Robert Mueller is treading carefully, but doesn't seem intimidated. For the madman theory to succeed, the practitioner must only "simulate" madness, while cannily anticipating his adversaries' goals and moves and planning precisely how he wants it all to turn out. But what happens if the madman isn't capable of intricate planning and calculation? What if the madman act isn't merely an act?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

William Falk is editor-in-chief of The Week, and has held that role since the magazine's first issue in 2001. He has previously been a reporter, columnist, and editor at the Gannett Westchester Newspapers and at Newsday, where he was part of two reporting teams that won Pulitzer Prizes.

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred