There's still only one way to tackle climate change

Always be cutting emissions

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Promising news on the climate technology front: Harvard scientist David Keith and his colleagues have published a paper demonstrating a workable, fairly cheap way of removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Good stuff!

However, this is also an opportunity to review the obvious fact that the cheapest, easiest, and most responsible climate policy is to smash down emissions as fast as possible — even taking this new technology into account. As yet, no simple technology is going to save us from ourselves.

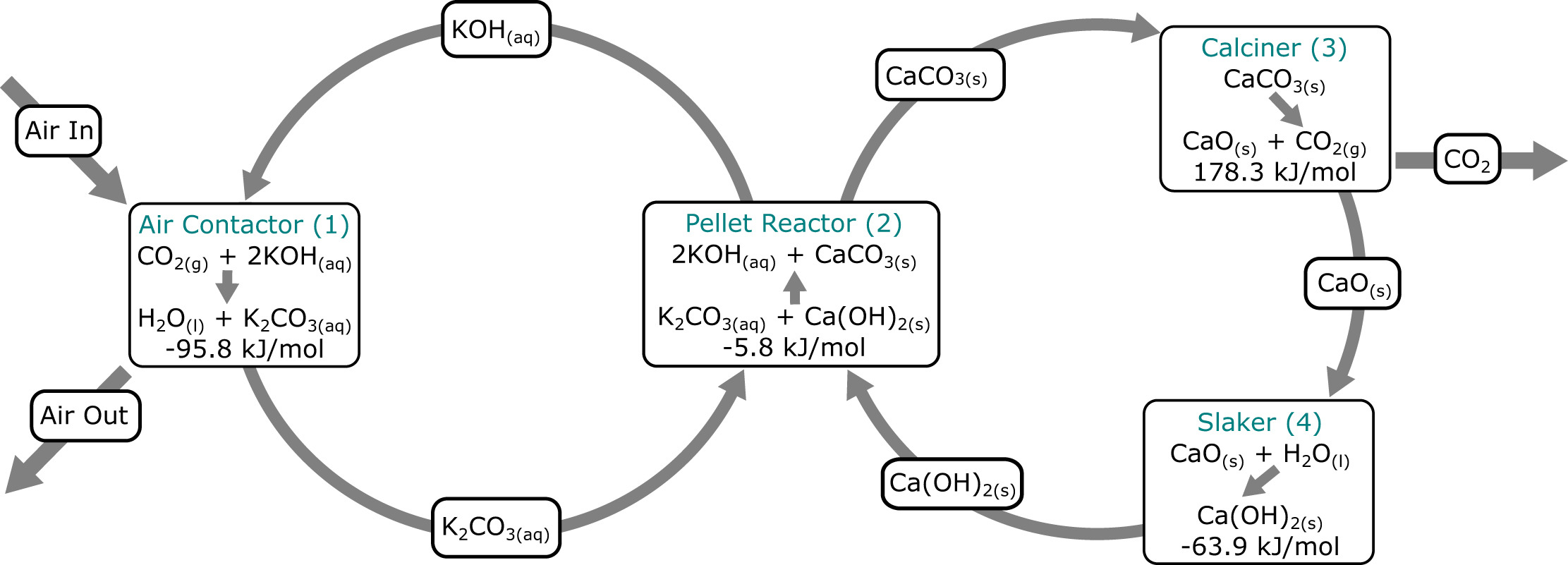

So how does Keith's tech work? In brief, researchers set up a cooling tower which sucks in air and uses some clever, efficient chemistry to separate out the carbon dioxide and turn it into carbon fuels. First, outside air is put through a sophisticated apparatus containing a potassium hydroxide solution (a strong base), which reacts with carbon dioxide (a weak acid) to produce potassium carbonate and water. Second, the potassium carbonate solution is reacted with calcium hydroxide pellets, which produces calcium carbonate plus the original potassium hydroxide, which can then be fed back into the first reaction.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Then the calcium carbonate is put through a high-temperature reaction to remove pure carbon dioxide, leaving calcium oxide left over. React that with some water, and hey presto, you've got calcium hydroxide again, which can be used in the second reaction above. It's two complete interlocking reaction loops, taking in air at one end and producing pure carbon dioxide at the other:

And once you have pure carbon dioxide, it's just one more bog-standard industrial reaction to make carbon fuels like octane.

Of course, that's a drastically simplified picture of what's going on. The researchers had to sweat and tinker for years to make the idea work — indeed, it's a good example of what it takes to start with an industrial process which checks out according to scientific theory, and actually produce a functioning prototype. There were enormous headaches and obstacles; they note that they have "now spent roughly 100 person-years on such apparently trivial items to develop a process proposed almost two decades ago by Klaus Lackner and collaborators."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But now they have a plant which has been functioning since 2015, and processing about one metric ton of carbon dioxide per day. They estimate their costs at industrial scale as between $103 and $255 per metric ton (obviously the final price will depend a great deal on unknowable details of scaling up the process). That's pretty good!

However, contrary to an Atlantic headline promising that "Climate change can be stopped by turning air into gasoline," this is not remotely a good way to stop climate change. For one thing, this is so far a one-metric ton demonstration plant, and global carbon dioxide emissions were 32.5 billion metric tons in 2017. Simply to process that single year's worth of emissions would cost, by their estimates, between $3.3 trillion and $8.3 trillion — and that doesn't even include the costs to build the gargantuan industrial complex necessary to take that much carbon dioxide out of the air. To actually stop climate change, we would have to remove vastly more than that — and then store it underground somewhere, which wasn't even part of the project.

Instead, the researchers initially propose using the fuel for transportation — in effect, removing carbon dioxide from the air and then putting it right back. While that is better than burning oil from the ground, it makes it even less useful for stopping climate change. (To be fair, in the article itself, Keith frankly admits this: "My view is we should stick to trying to cut emissions first. As a voter, my view is it’s cheaper not to emit a ton of [carbon dioxide] than it is to emit it and recapture it.")

Sensible, small-c conservative climate policy — if we were trying to save money, minimize risks to the United States, and preserve it in as close to its current form as possible — would require developed nations to cut their emissions by something like 10 percent per year. (Or more realistically, just cut as fast as we possibly could.) Technologies like Keith's can help on the margin, by making existing fuel systems less carbon intensive, and perhaps suck some carbon out of the air after some more innovations.

I fear it is a lot more likely that stuff like this will be used in a total panic in about 50 years, after we dawdle and whine, only to black in and find Miami miles out to sea. But it remains true that the smart move is to cut emissions now as fast as we can.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Are zoos ethical?

Are zoos ethical?The Explainer Examining the pros and cons of supporting these controversial institutions

-

Will COVID-19 wind up saving lives?

Will COVID-19 wind up saving lives?The Explainer By spurring vaccine development, the pandemic is one crisis that hasn’t gone to waste

-

Coronavirus vaccine guide: Everything you need to know so far

Coronavirus vaccine guide: Everything you need to know so farThe Explainer Effectiveness, doses, variants, and methods — explained

-

The climate refugees are here. They're Americans.

The climate refugees are here. They're Americans.The Explainer Wildfires are forcing people from their homes in droves. Where will they go now?

-

Coronavirus' looming psychological crisis

Coronavirus' looming psychological crisisThe Explainer On the coming epidemic of despair

-

The growing crisis in cosmology

The growing crisis in cosmologyThe Explainer Unexplained discrepancies are appearing in measurements of how rapidly the universe is expanding

-

What if the car of the future isn't a car at all?

What if the car of the future isn't a car at all?The Explainer The many problems with GM's Cruise autonomous vehicle announcement

-

The threat of killer asteroids

The threat of killer asteroidsThe Explainer Everything you need to know about asteroids hitting Earth and wiping out humanity