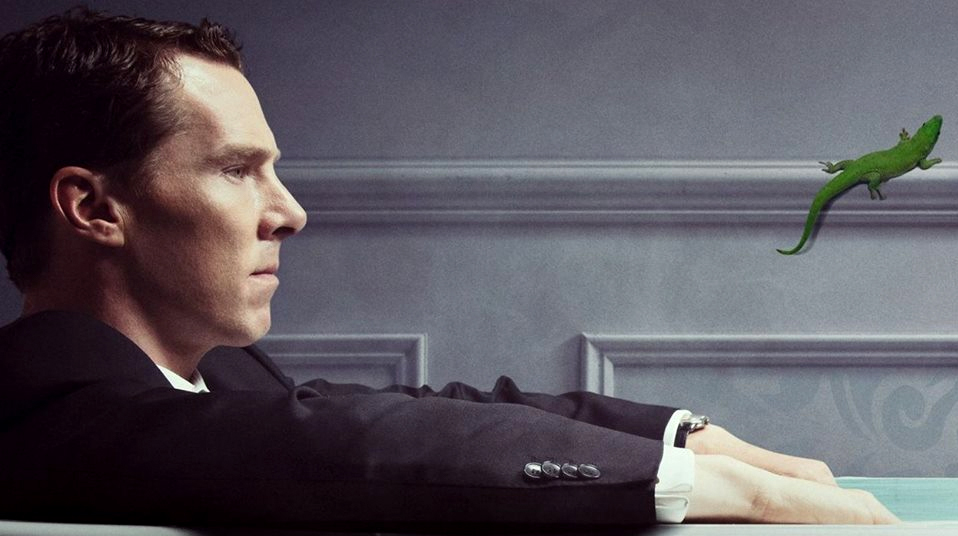

Patrick Melrose and the misery of wealth

Examining the glamour and poison of the Benedict Cumberbatch-led Showtime miniseries

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

How can the rich be unhappy?

It often seems to beggar belief. Material woes — the need to pay the rent and to feed oneself and one's children — seem so vast and crushing that it is hard for many people to imagine despair beyond them, up in the lofty heights. And yet in the well-appointed eyries of the rich a separate species of human misery can flower, one cut off from the masses, but no less absolute.

Patrick Melrose, a BBC miniseries whose finale aired over the weekend on Showtime, is a grim excavation of the lives of the idle rich. Based on a series of acerbic, confessional novels by Edward St. Aubyn, published over the span of two decades, the series captures slices of the titular character's complex, scarred life, one shaped in equal measure by wealth and by trauma. The five slim volumes have become five hours of electric and difficult television, peopled by heiresses and junkies and sometimes both in the same person. The show gives an intimate look at a life of inherited wealth — and all the ugliness and tumult that can be hidden within such a life.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The desire to look into the drawing rooms and bedrooms of the wealthy, and see firsthand the depravity and despair unfolding there, is an old cultural mania. From Tolstoy's tormented nobles to the unearned luxury of the "SoHo grifter"; from the novels of Dominick Dunne to The Real Housewives, we all thrill a bit at peeking in at a lifestyle that far outstrips any we could hope to attain through sweat or pluck. What is it we hope to see besides proof that our own faults are mirrored there? There is a certain ugliness to wealth-gawping; so often it is motivated as much by a desire to see the golden people fall as it is to attain their exalted heights. Is it a comfort, or a sadistic thrill, to know that even in the walled gardens of wealth, the twisted vines of human nature grow?

Patrick Melrose takes this idea of the miserable wealthy to an extreme, with the rape of Patrick at the age of 8 by his father David. Patrick never recovers, even as an adult against the backdrop of a sprawling estate in Provence, a magnificent party at a noblewoman's mansion, and glamorous hotels in New York. Benedict Cumberbatch, playing Patrick, uses his protean features to advantage in a role that demands he portray ironic detachment, heroin withdrawal, delirium tremens, profound sorrow, and sometimes — rarely — faint hints of surfaced joy.

We see Patrick in an array of moods, from mania to torpor, and although the show does not shy from the agonies of his heroin addiction or agoraphobia, it portrays the eternal return of his childhood trauma with restraint and grace. The visual shorthand of the series — a mahogany door shutting, a pair of brogans dropped beside a bed, a child's hands tightening on the basin of a sink — serve to gesture at horror more vividly than a direct gaze could. Patrick's lifelong grief and anger, which he seeks perpetually to drown in a flood of intoxicants, is enhanced by the uselessness of the social set that surrounds his father: vain intellectuals, witty dandies, hangers-on, aspirants to the luxurious boredom of the Melroses' lives. ("What one aims for is ennui," David Melrose says to his guests at a dinner party.)

In America, class is rarely conveyed by title. Instead, it manifests in teeth and hair and clothing and dwelling and ease, in influence and invitations. Class privilege coalesces into dynasties without anything so crude as a barony or a lordship to limit it. Celebrity often serves as a proxy for class: give or take a few centuries, and MTV's Cribs and BBC documentaries about castles have much in common. At the core of class privilege is idleness: the ability, among the children of the wealthy, to do nothing at all to earn their bread. The old American dream is about working hard to make it, but its ultimate culmination is in idleness, and the idleness of one's children.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

On reality television and in the pages of gossip magazines, that idleness is dissected, both in its material trappings (for sale, if you can afford it) and its most banal minutiae. But it's when that idleness curdles into something more rotten that we find ourselves breathless with fascination, when public attention accelerates into feverish obsession. So we gleefully digest the public breakdowns, complicated pregnancies, and torturous divorces of celebrities; the Bronfman heiresses' alleged embroilment in a sex cult; Anna Delvey punishing rich kids for their endless guile. We will buy custom-branded makeup lines and perfumes and T-shirts, but we will devour despair and demise just as gladly, and on primetime, too.

In a sense, Patrick Melrose is a rebuke to the culture of fascination with the wealthy, and the barely concealed schadenfreude of the public panting for their pain. Its minute observations of the upper classes — a scathing portrait of Princess Margaret at a party stands out — cater to that craving, but it is sated at a price. The series is not a paparazzo snapshot of heirs and heiresses behaving badly; it is a minute and tragic portrait, in living color, of a life rotted from within. The series draws you in close to the lighted window of the palace, but what you see through the curtains is an ugliness impossible to forget.

Talia Lavin is on the editorial staff at The New Yorker. She is the author of the weekly Harpy column at the Village Voice, and hte bi-monthly Apikoress column at the Jewish Daily Forward. She loves dogs, cats, and men, but owns none of the above.

-

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960s

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960sThe standout shows of this decade take viewers from outer space to the Wild West

-

Microdramas are booming

Microdramas are boomingUnder the radar Scroll to watch a whole movie

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'The latest biography on the elusive tech mogul is causing a stir among critics

-

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!The Explainer Please allow us to reintroduce ourselves

-

The Oscars finale was a heartless disaster

The Oscars finale was a heartless disasterThe Explainer A calculated attempt at emotional manipulation goes very wrong

-

Most awkward awards show ever?

Most awkward awards show ever?The Explainer The best, worst, and most shocking moments from a chaotic Golden Globes

-

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. deal

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. dealThe Explainer Could what's terrible for theaters be good for creators?

-

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'The Explainer Move over, Sam Elliott and Morgan Freeman

-

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020feature So long, Oscar. Hello, Booker.

-

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortality

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortalityThe Explainer This film isn't about the pandemic. But it can help viewers confront their fears about death.