How Trump exploded America's absurd moralism about foreign affairs

This may well be the president's greatest accomplishment

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The Singapore summit between President Trump and North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un appears to have mostly been a farce in which the American president (due to a mixture of ignorance and misplaced bravado) mistook a mutual restatement of vague goals regarding denuclearization of the Korean peninsula for some kind of diplomatic breakthrough. Because of that misunderstanding, the future of relations between the United States and North Korea remains fraught and highly risky.

Yet there is one respect in which the meeting was unambiguously positive: the fact that it happened at all.

Americans love to think well of themselves, especially when it comes to questions of moral purity. We imagine ourselves on the side of the angels, an exceptional nation that stands for human rights and democracy and against tyranny in all of its forms. Because of these assumptions, we like to divide the nations of the world into two categories: those belonging to the "free world" (of which the U.S. is the undisputed leader) and everyone else, ranging from the merely corrupt to the actively malevolent.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

For the nations we place in the latter, most sinister category, the only supposedly acceptable outcome is isolation, quarantine, reprimand, and denunciation. The message is: We're too good for you; you're too foul for us. We won't even talk to you. Or if we do talk to you, it will be in the form of chastisement and hectoring demands. And we certainly won't trade with you. More likely we'll impose economic sanctions, ensuring your people suffer and remain poor, because the internal workings of your country are our business, and the way we'll force a change is to goad your people into rising up and overthrowing your government, and maybe even by helping them to do this through various covert means.

These moralistic assumptions frame discussion and analysis whenever an American president dares to gesture toward engaging in normal diplomatic relations with the leadership of non-democratic countries. Barack Obama faced it for talking with the governments of Iran and Cuba, and so did Ronald Reagan in his efforts to reach arms-control agreements with the Soviet Union. Such acts of engagement are invariably ridiculed as telegraphing weakness or, worse, a capitulation to evil.

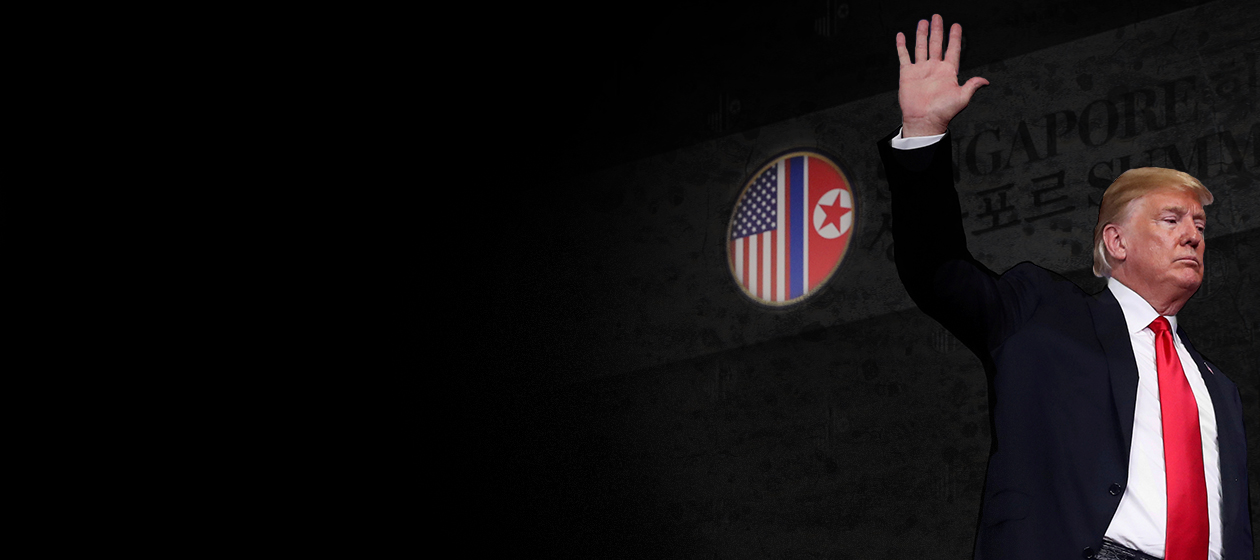

We saw this reaction throughout coverage of the Trump-Kim summit.

Just look at how the American and North Korea flags have been placed next to each other, as if Pyongyang and Washington are equally worthy of respect. Appalling!

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What? Trump has spoken admiringly of his North Korean counterpart? You mean he didn't call the regime a totalitarian tyranny or describe the country as a concentration camp to Kim's face? What a fool!

An appalling fool he may be, but Trump's instinctive lack of moralism — his tendency to think in tribal terms rather than abstract, universal principles that just so happen to be instantiated in the United States, which has been empowered by providence to bring our form of government to every corner of the globe — makes him uniquely well-suited to cut through the pious nonsense.

The United States has many admirable qualities, but it does not belong in a distinct moral category from the other nations of the world, just as no one has appointed it judge, jury, and executioner of international justice, or authorized it to separate the righteous nations from the wicked.

That relative absence of moralism also helps Trump to avoid the hypocrisy to which America is especially prone. You know, the hypocrisy of lecturing other countries about their moral failings when we cultivate friendly and mutually advantageous ties with the theocratic totalitarians of Saudi Arabia, who are currently pummeling the poorest country in the Middle East (Yemen) with our blessings and logistical support. Never mind our own history of morally dubious actions at home and abroad, including the only battlefield use of atomic weapons in world history (against a civilian population no less), the dropping of incendiary bombs on city centers in Germany and Japan, the carpet bombing of Korea and Vietnam, and the hundreds of thousands of Iraqis killed in violence unleashed by our invasion of the country. Even the relatively antiseptic drone warfare of the past decade has killed thousands of civilians in a long list of countries.

The point isn't to suggest that the United States is exceptionally evil. It's to suggest quite the opposite — that the United States isn't particularly exceptional at all. We're a well-meaning and extremely powerful nation that's prone to the same faults as any other, including arrogance, hubris, foolishness, and callousness.

In this respect, and perhaps in this respect alone, Trump is likely to have a salutary influence. He will talk with anyone, provided his interlocutor displays adequate respect. The emphasis on respect can certainly lead to horribly stupid and counterproductive tension with allies when Trump feels they have personally slighted him, as appears to have happened at the G-7 meeting last weekend in Quebec. But the president's willingness to engage across moral divides may well teach Americans the valuable lesson that nothing is lost, and quite a lot can be gained, by talking, negotiating, and learning to live with anyone.

If Trump manages, despite himself, to lead the country to let go of some of its heavy-handed moralism, then he will have redeemed at least a little bit of the farce.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.