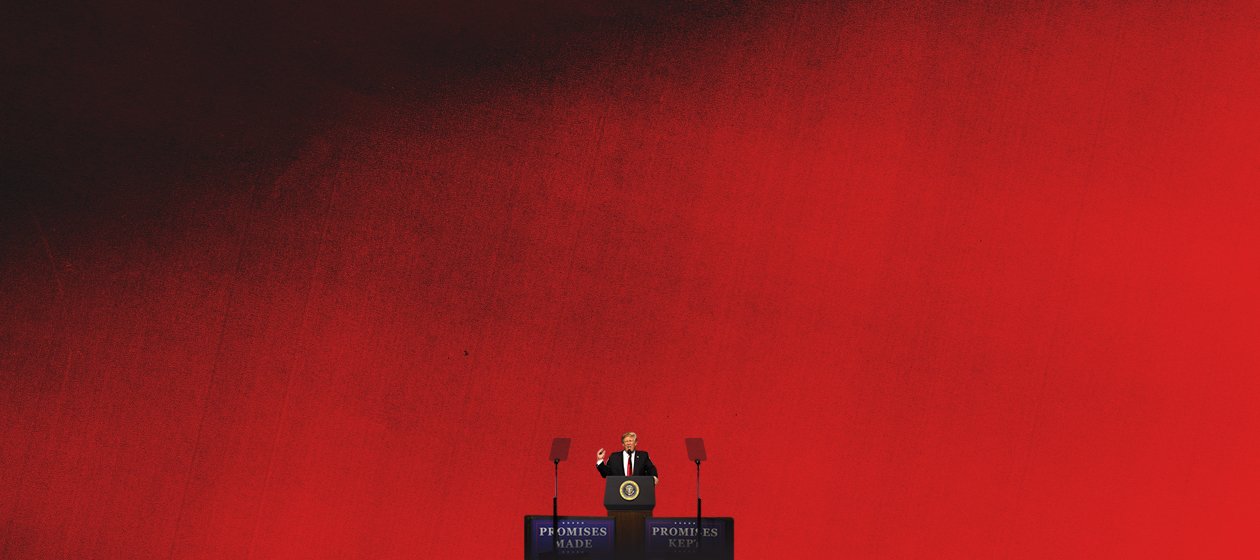

The GOP's minority rule

Can a country remain a liberal democracy while abandoning majority rule? We're on the verge of finding out.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Can a country remain a liberal democracy while abandoning majority rule?

The Republican Party in the 21st century appears exceedingly eager to explore the question — and far too indifferent to the answer.

The norms and institutions of our form of government are designed to accomplish many things, but one of the most essential is the translation of public opinion into policy. Our government is supposed to represent the interests and preferences of the people. When a government fails to do this — when it seems to act apart from or at odds with public opinion — it can justly be said to have failed in one of its core functions and so undermined its own legitimacy.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

One way that ostensibly democratic governments seek to represent public opinion is through the principle of majority rule (or plurality rule, when no majority is present). The animating idea behind the principle is that, because "the people" have contrary and clashing interests and preferences, whichever cluster of interests and preferences are held by the greatest number of individuals should receive the lion's share of the political power at any given time.

To this principle, the American system of government adds various counter-majoritarian veto points. These are ways for minority factions to stymie the will of the majority or plurality, ensuring (in theory) that bold action favored by a large portion of the population but strongly opposed by a smaller portion of the population will be slowed down, forced to moderate, or halted altogether.

What we have seen in recent years is something else entirely. George W. Bush lost the 2000 presidential election by roughly half a million votes and yet won the presidency with the help of two counter-majoritarian institutions — the Electoral College and the Supreme Court. President Trump lost the popular vote by 3 million votes and yet won the presidency, this time because of the Electoral College alone. In 2012, Democrats in House races received nearly 1.5 million more votes than Republicans, yet due in large part to gerrymandered congressional districts, the Republicans won a majority of the seats by a margin of 234-201. Some models predict that in the upcoming midterm elections this November, Democrats could outpoll Republicans by 4, 5, 6, or even 7 percent while still failing to win a majority in the House.

Add it all up and we're left with something perilously close to minority rule. This is pure civic poison.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

It would be one thing if Republicans were aware of the problem and governed accordingly — with humility, seeking compromise and conciliation with the popular majority that opposes their agenda. But that isn't at all the Republican response. On the contrary, on immigration, trade, relations with Russia, tax policy, health care, and a host of other issues, the Trump administration has pursued policies opposed by a plurality or even a majority of the country.

When liberals object, the response from conservatives is usually some version of "whataboutism" — the reflexive pointing to ostensibly similar behavior on the part of Democrats: "What about when the left was in power, like it was from the New Deal until the 1980s? Through those decades the Democrats routinely enjoyed House majorities that far surpassed their share of the popular vote!"

That's true. In 1940, for example, Democrats in House races won 51.4 percent of the vote and yet ended up with 61 percent of the seats. Likewise, in 1964, Democrats won the popular vote in the House with 57.1 percent while ending up with a supermajority of 67.8 percent in the chamber. That was the Democrats using gerrymandering to enhance their political power, just as Republicans are doing today.

But there's one small but crucially important difference: Through those years of Democratic control, the majority party used gerrymandering to amplify its support among a majority of the country's voters. Today, by contrast, the Republican majority uses gerrymandering to thwart the wishes of a majority of the country's voters.

In our first-past-the-post, winner-take-all electoral system, some amplification is unavoidable. In a two-person race, the candidate who finishes with 50 percent-plus-1 earns 100 percent of the power of the office. When there are more than two candidates, the winner walks away with just as much power even when he or she wins considerably less than a majority. (Bill Clinton became commander in chief after winning just a 43 percent plurality of the vote in 1992, when independent Ross Perot won nearly 19 percent in the strongest third-place finish in modern history.)

The kind of gerrymandering that produced the results in the 1940 and 1964 House races merely enhances this tendency. It's not a great feature of the system, since it distorts the popular will, convincing the party in the majority that its support is stronger than it really is. But at least it doesn't contravene the popular will.

The same cannot be said of what happened in the 1942 midterm election, when Republicans managed to outpoll Democrats in House races by more than a million votes while falling short of winning a majority of seats 222-209. That was the last time prior to 2012 that congressional gerrymandering had the effect of thwarting public opinion.

What the country is facing in 2018 is something far more troubling. The Republican president attained his office despite losing the popular vote by millions. He has pursued an agenda sharply at odds with the preferences of those who voted for his opponent. He has governed erratically and remains deeply unpopular among both Democrats and independents. Due to the norm-shredding, thuggish tactics of the Republican majority leader in the Senate, the president is making his second lifetime appointment to the counter-majoritarian Supreme Court, which may well entrench Republican power in the nation's highest court for decades to come while endangering landmark decisions supported by a majority of the country.

And on top of all of that, a combination of extreme gerrymandering at the state level and the clustering of Democrats in high-density congressional districts threatens to diminish the electoral impact of a building wave of anti-Republican sentiment.

If Democrats fall short of taking majority control of the House while winning a majority of the ballots cast in November, it will be the surest sign yet that the United States is evolving into a country with a political system marked by minority rule.

How will the majority respond to a situation in which its will is systematically thwarted? Will activists, journalists, and celebrities throw impotent tantrums on Twitter while most Americans shrug their shoulders in indifference, resigning themselves to political powerlessness? Or will millions of the disempowered take to the streets in angry protests against a system that refuses to respond to and represent the views of the majority?

There's no way to know for sure. But about one thing we can be certain: If people demand an end to their own disenfranchisement, they will be fully justified.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.