How Americans grade the economy on a curve

This is what consumer sentiment really tells us

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Just how well is the U.S. economy doing?

This is actually a point of some contention in wonk world. Unemployment is remarkably low, GDP growth is strong, and the stock market is booming. On the other hand, wage growth is anemic, labor force participation is still depressed, and household finances remain precarious.

One way to cut through the murk might be to ask Americans themselves for their opinion.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

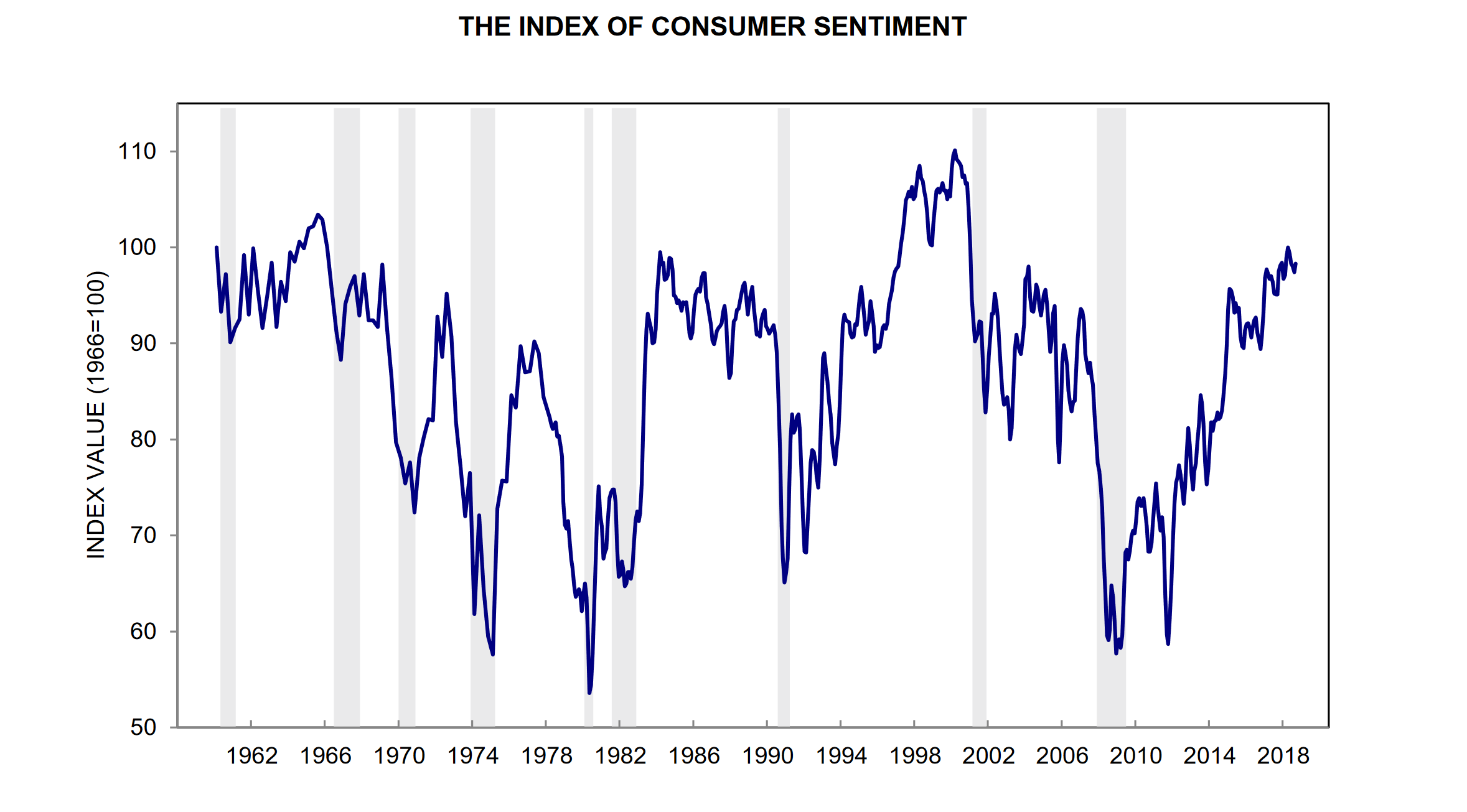

Pew, Gallup, and other outfits all do regular surveys asking people how they think the economy is doing. And these days, results from these questionnaires suggest the economy is doing quite well. According to the University of Michigan's survey of consumer sentiment — arguably the gold standard of these efforts — things are as good as they were in the early 1960s.

That seems to settle the question: We're back to the boom years of the mid-century!

But what if Americans grade the economy on a curve?

Taking the above graph as evidence the American economy is back to full health requires an implied assumption: That if you asked an American in 1962 and an American in 2018 to describe a "good" economy, they'd both describe the same thing. In wonk-speak, you're assuming their baseline for judging the economy has remained unchanged over time.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But that's actually a pretty silly assumption to make. Richard Curtin, the University of Michigan economist who runs the surveys, points out in his own research that respondents are only human. If you ask them whether the economy is good or bad, they must, even if only unconsciously, first answer the question "compared to what?" Most people today don't even have direct memories of the 1960s. Many more people were around for the late '90s boom, but even that is now filtered through the haze of time. What most people understandably end up instinctively doing is comparing the current economy to more recent experience.

"You look at 3 percent growth in the mid-'60s, and people would say, hey, this is getting troublesome," Curtin told The Week. "But over the past 10 years, how does 3 percent or 4 percent GDP growth look? It looks pretty good!"

If you dig a little into the Michigan survey data, the problem becomes visible quite quickly.

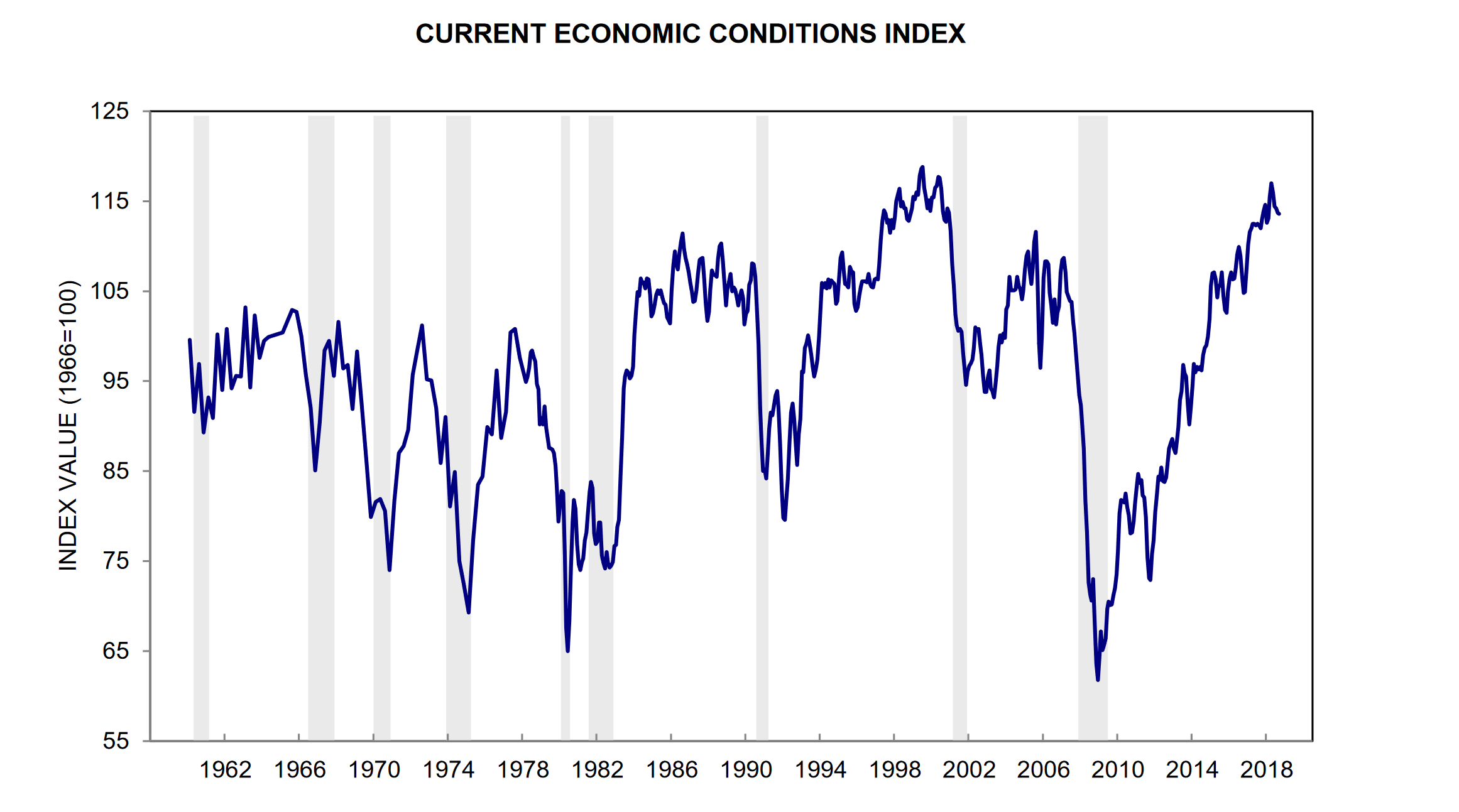

The survey actually has multiple subcomponents. One asks people about current economic conditions — how they're doing right now. The other asks about their expectations — how they think they'll be doing in the near future. And if you think the results from the overall consumer sentiment index are remarkable, you should see how Americans assess current economic conditions specifically.

Not only are current economic conditions assessed as roughly the best ever in the survey's history, but conditions have been steadily improving the whole time. This is a bizarre result, frankly. In the 1960s "personal income was going up by 5 or 6 percent — real personal income," Curtin told The Week. Over the last year, real income growth has been close to zero, and has been stagnant for most Americans for decades. You can make a plausible argument that Americans as a whole are as economically well off today as they were in 2006 or 2007. But it's a stretch to argue things are as good as in 2000, nevermind the 1960s.

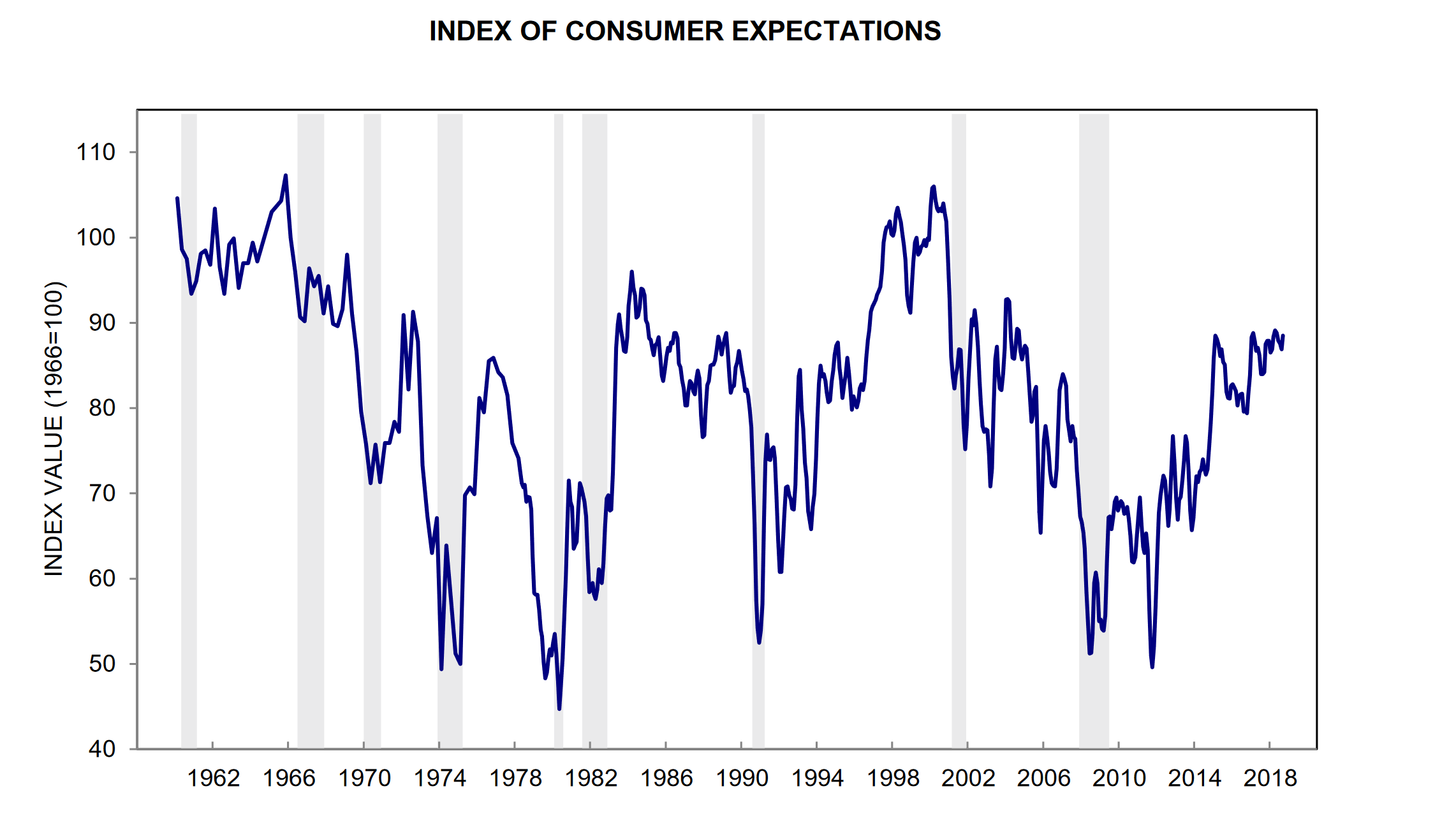

If you look at the survey of expectations, i.e. what people think will happen in the future, the mystery deepens.

On its own, this graph is a lot more reasonable: Americans' optimism about the future is lower today than in the mid-century or at the end of the Clinton boom. Instead, it's about where it was in the mid-1980s, during the recovery from another particularly brutal crash.

But how can Americans be reporting the best economic conditions, perhaps ever, while also reporting middling expectations for the future?

The answer, Curtin suggested to The Week, is that people surveyed respond to changing conditions over time by instinctively adjusting their benchmark for a "good" economy. If you have a big shock like a recession, people will obviously realize they're in unusually bad times. But if there's been a long slow decline in economic conditions — and there has been — people's standards get beaten down as well. An economy they would've once ranked as mediocre or even bad starts getting ranked as decent or good.

"When you ask how are we doing today, well, we're doing much better than a few years ago," Curtin said. "That's what they're telling us."

In fact, Curtin has done some statistical tests of the survey data, and concluded that people tend to use the last decade as their benchmark. "I took the index components and took averages of GDP growth, income growth, etc, and I looked at different windows for those averages," he explained. "The 10-year average of GDP growth fit the changes in how consumers were judging the economy best." Ten years ago we were in the depths of the Great Recession. So yes, today's economy looks amazing by comparison.

Certainly, none of this means Michigan's consumer survey or any of the other surveys are bad information or "fake news." It simply means you can't take them as a purely objective barometer over time, either. There's a crowd psychology at work we need to be aware of — people's aspirations, and what life has taught them they can (and can't) dare to hope for.

And when people get beaten down long enough, they can lose track of what was once possible.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The pros and cons of noncompete agreements

The pros and cons of noncompete agreementsThe Explainer The FTC wants to ban companies from binding their employees with noncompete agreements. Who would this benefit, and who would it hurt?

-

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contraction

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contractionThe Explainer The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

-

The death of cities was greatly exaggerated

The death of cities was greatly exaggeratedThe Explainer Why the pandemic predictions about urban flight were wrong

-

The housing crisis is here

The housing crisis is hereThe Explainer As the pandemic takes its toll, renters face eviction even as buyers are bidding higher

-

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkers

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkersThe Explainer Show up for your colleagues by showing that you see them and their struggles

-

What the stock market knows

What the stock market knowsThe Explainer Publicly traded companies are going to wallop small businesses

-

Can the government save small businesses?

Can the government save small businesses?The Explainer Many are fighting for a fair share of the coronavirus rescue package

-

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shock

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shockThe Explainer This could be a huge problem for the entire economy