Why Democrats win purple states

Part of the reason is that these Democrats sound like throwbacks

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When Bernie Sanders surprised no one by failing to secure the Democratic presidential nomination in 2016, for some of us the writing was on the wall. Not only was Donald Trump going to beat Hillary Clinton — he was almost certainly going to win most of the so-called "purple" states — Ohio, Florida, Pennsylvania, and even Michigan, where the most reliable predictor for November is the United Automobile Workers' endorsement in the Democratic primary. The union sat out the race in 2016, and Sanders beat Clinton. While exact figures are not available, it is certain that a huge number of those who voted for Sanders in the primary must have swung in November to Trump.

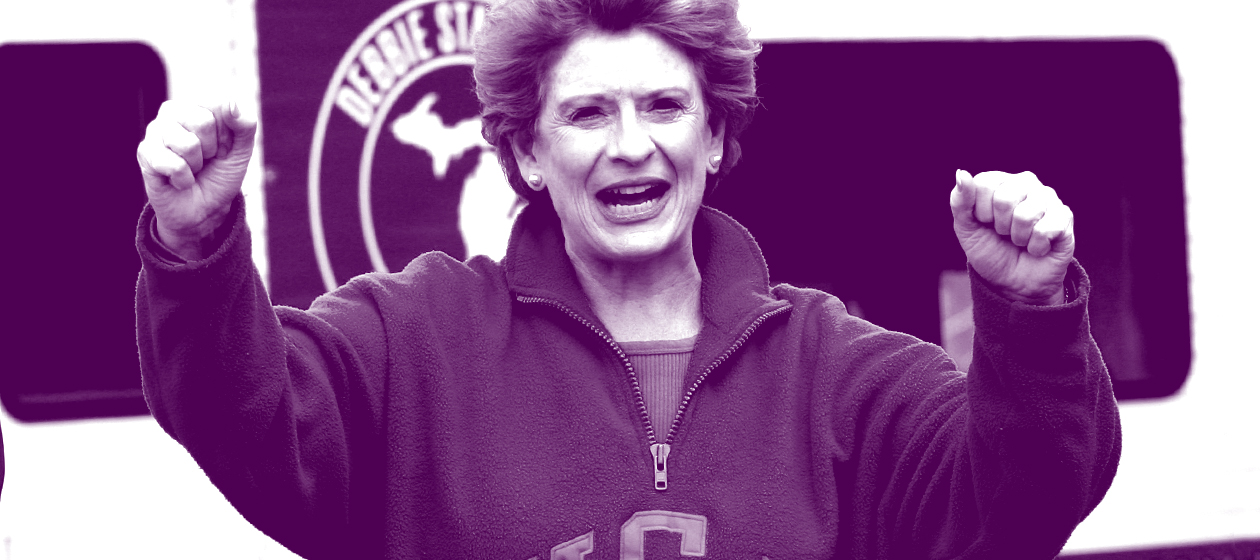

No one, however, least of all Republicans, has expected Trump's victory to translate into other significant national-level gains for the GOP in Michigan, a state that has not elected a Republican senator to two terms in the post-war era. John James, a distinguished veteran of the Iraq War and businessman, captured the GOP Senate nomination with ease, thanks in part to an endorsement by Trump. But Republican primary voters are not representative of the Michigan electorate. James is polling behind the incumbent Democratic Sen. Debbie Stabenow by an 18-point margin. Forty percent of voters in Michigan (where I live) have never even heard of him.

Why do Democrats win statewide office in Michigan? Part of the reason is that Michigan Democrats sound like throwbacks. In her television spots, Gretchen Whitmer, the former state Senate minority leader who is now running for governor, talks about getting tough on crime. In a recent ad, Stabenow appears on camera with a group of farmers, including one self-identified Republican. These men do not seem especially concerned with her views on Planned Parenthood or the provision of restroom services to gender nonconforming individuals. Instead they praise Stabenow for her championing of their interests in Washington, where she was the chairman of the Senate Agriculture Committee from 2011 until 2015. Her environmental record — including her opposition to mandatory GMO labeling — is appalling to national progressive outfits. But she wins.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

While it is true that in Michigan bread-and-butter issues — jobs, the condition of roads, the quality of schools — dominate political discourse, there are social issues that divide voters. The most significant of these is not abortion (which is not widely available outside of urban areas) or same-sex marriage (which was outlawed in 2004 after a statewide ballot initiative, before being legalized nationwide by the Supreme Court in 2015), but race.

This has been true for more than half a century. In 1960, Genesee and Wayne had the highest GDP per capita of any counties in the United States — indeed, the highest in the world. But this prosperity was only possible because it deliberately excluded the large African-American populations of Flint and Detroit. The myth of a golden age of prosperity for factory workers and skilled tradesmen to which both Trump and Sanders alluded is the most powerful rhetorical force in Michigan politics.

Meanwhile the racial disparity that characterized the state at its zenith has continued well into its decline. Four years after it was discovered that the water supply in the majority African-American city was toxic, the Flint water crisis is nowhere close to being solved, put out of mind as quickly by other Michiganders as it was by the rest of the country. Republicans earlier this year attempted to create work requirements for Medicaid that would only apply to residents of Detroit and Flint and the surrounding areas. The drawing of legislative districts has always been a nakedly racial question, and an easy one for the Republicans who control the state House and Senate to solve given the concentration of the state's black population within a handful of urban counties.

This is not to suggest that only Republicans have contributed to Michigan's racial polarization. In 2018 one of the most discussed issues in Michigan is the price of car insurance. Michiganders pay more to insure their vehicles than residents of any other state thanks to ludicrous "no-fault" provisions in state law. Attempts at reform led by Republican legislators have been defeated on numerous occasions by Democrats. One consequence of this is that in Detroit nearly half of drivers risk heavy fines and even the loss of their licenses by driving without insurance.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In 1972, George Wallace won Michigan Democratic presidential primary handily. (I know several people who can claim to have voted both for the man who infamously stood in the doorway and for our first black president.) From the beginning of the post-NAFTA era until very recently, open calls for the restriction of immigration have been a mainstay of union politics.

Here it is interesting to recall the fate of Spencer Abraham, a co-founder of the Federalist Society and Michigan's last Republican senator. Abraham lost his seat to Stabenow in no small part thanks to a campaign by the Federation for American Immigration Reform. "Why is Sen. Spencer Abraham trying to make it easier for terrorists like Osama bin Laden to export their war of terror to any city street in America?" the group asked in newspaper advertisements and television commercials. This was ostensibly a reference to Abraham's moderate views on immigration, but it was also an obvious dog-whistling allusion to the fact that he was at the time the only person of Arab descent serving in the Senate. At the time his opponent refused to denounce or even acknowledge the existence of the ads. These are the conditions, now forgotten, under which Stabenow's now ironclad majority came into existence.

As with many of the most serious problems in American life, there is no obvious solution to the racial divisions in Michigan politics. They are a fact of geography as much as anything else. But it is interesting, if nothing else, for political observers to look at this state, where a black Republican is about to lose a Senate race in a landslide to a white woman whom the left sneers at as a "Monsanto mouthpiece," and whose next governor will be chosen largely on the basis of his or her ability to talk tough about crime and the drug war, when they make generalizations about the state of our politics.

Matthew Walther is a national correspondent at The Week. His work has also appeared in First Things, The Spectator of London, The Catholic Herald, National Review, and other publications. He is currently writing a biography of the Rev. Montague Summers. He is also a Robert Novak Journalism Fellow.

-

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first time

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first timethe explainer Tackle this financial milestone with confidence

-

The biggest box office flops of the 21st century

The biggest box office flops of the 21st centuryin depth Unnecessary remakes and turgid, expensive CGI-fests highlight this list of these most notorious box-office losers

-

What are the best investments for beginners?

What are the best investments for beginners?The Explainer Stocks and ETFs and bonds, oh my

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred