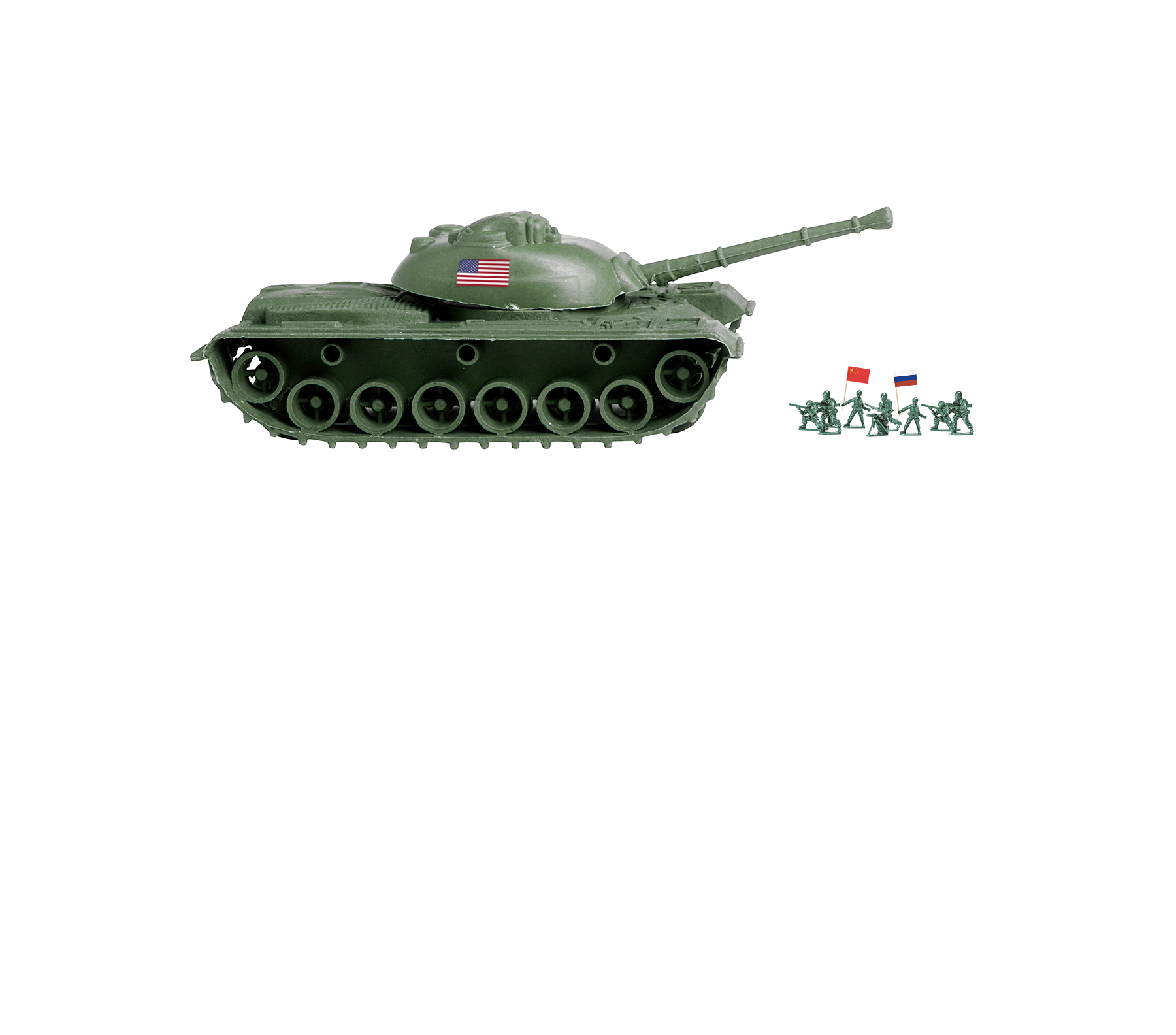

The paranoid delusions behind American foreign policy

Our military dwarfs everyone else's. So what is America so scared of?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Imagine a wealthy man who has an unhealthy obsession with ensuring he'll be safe everywhere he goes. Maybe he learns a range of martial arts and trains himself in the use of firearms that he stockpiles in his home and his car. Then he purchases the most advanced form of body armor he can find. Soon he's spending many times more than any of his neighbors on his own security — yet he nonetheless concludes that he's in mortal danger and must spend far more just to mollify his fears.

The United States is this paranoid, anxiety-addled man.

That's my conclusion from reading a report released on Wednesday by the bipartisan National Defense Strategy Commission. The purpose of the commission, whose members were chosen by Congress, was to evaluate the Trump administration's 2018 National Defense Strategy, which portrayed a world of renewed great power competition between the U.S., China, and Russia. Is the American military up to the task? That's the question the commission's members, former top Republican and Democratic officials, sought to answer. Their conclusion: The U.S. is in serious trouble globally, with threats confronting it around the world and Congress allocating insufficient resources in response to the danger. If that doesn't change — if we don’t significantly increase our spending on defense — the U.S. could well find itself fighting a war with China or Russia that it would lose.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

That sounds scary. But it's not nearly as frightening as the thought that leading members of both parties think about international relations and American foreign policy in such delusionally fearful terms.

Deep in the Washington Post story about the commission's report comes a statistic that exposes the pathological unreasonableness of the entire exercise. The "$716 billion American defense budget this year," the Post informs us, "is four times the size of China’s and more than 10 times that of Russia." (The Post might have added, for greater context, that the U.S. also spends more on defense than the next seven most powerful countries in the world combined.)

This is supposedly cause for alarm about our vulnerability?

There is only one way to reach such a conclusion — and that is to view the world through a set of seriously twisted assumptions.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In this case, the most twisted assumption of all is that the U.S. can only consider itself safe and its interests protected if it maintains clear and unambiguous military primacy around the world. We need to be not only the most powerful country on the planet, but the most powerful country on the planet by far — able to fight and decisively win a war with a major rival anywhere in the world while also fending off one or more smaller rivals in other parts of the world at the same time. And we need to maintain this global primacy indefinitely, even as China (and India and Brazil and Russia) grow in economic and military strength and ambition.

The logic of this position is obvious: The U.S. needs to spend ever-more on defense in order to stay multiple steps ahead of rising rivals. The alternative to doing so — allowing those rivals to rise to positions of regional power — is to risk much worse and more costly military conflicts down the road. Better for the U.S. to bestride the world like an unchallengeable colossus, and pay the ever-mounting costs of doing so, than permit anything resembling a multi-polar world to develop.

This vision of American military primacy was first proposed during the early 1940s, as an alternative to the isolationism that dominated American political debate through the 1930s. It made a sort of sense in the aftermath of World War II, when a victorious U.S. was the only country in the world possessing atomic weapons and every rival power lay in ruins, with several of them burying and mourning several hundred thousand and even millions of dead soldiers and civilians.

For much of the Cold War, it shaped American thinking about international affairs — making it seem reasonable to wage wars in the name of self-interest on the other side of the globe. But it was also held at bay by the superpower rivalry itself, which kept either side of the conflict from conceiving of its reach in truly global terms. Each superpower had its satellites and sphere of influence that pushed back against and served as a check on the other's ambitions.

This ceased to be true with the collapse of the Soviet Union. Suddenly the U.S. was the only power standing. It was the "unipolar moment" — one that could and should be extended indefinitely. Now America defined its interests in breathtakingly broad terms. Our military didn't just need to defend our borders (which, with Canada and Mexico as neighbors, was simple, easy, and cheap). It needed to "spread democracy," not just as a check on a rival geopolitical system (as was the case from the mid-1940s to the late '80s) but in absolute terms: the more democracy, and the more markets, the better. Everywhere. Just as any sign of resistance to democracy and markets anywhere in the world looked like a threat. Other countries could rise economically, but only if they refrained from challenging the military, political, and economic primacy of the United States.

Now the U.S. was not only the world's policeman. It increasingly saw itself as international justice's judge, jury, and executioner and the self-appointed guarantor of world order. Just as a government rightly views challenges by private citizens to its monopoly on violence as a threat to its power and legitimacy, so the U.S. now treated any form of resistance to the "liberal international order" as a direct threat to its rule. America had becoming incredibly powerful — the most powerful nation in the history of the world — but our very inability to control every corner of that world served as evidence that we needed to become more powerful still.

That's the logic of the report released on Wednesday. It defines American interests so broadly that what happens in Russia's or China's near abroad appears to matter as much as what happens in Ottawa, Havana, or Mexico City. Overlearning the lessons of the 1930s eight decades later, the report sees the rise of any regional power — even one we outstrip in defense spending by a factor of four — as an enemy we will inevitably end up having to fight and defeat on the battlefield (while also fighting and defeating other enemies at the same time). No wonder the analysis always yields the conclusion that we're better off spending even more now as a kind of insurance against this always-worse imagined outcome.

It's an axiom of moral reasoning that one cannot be obligated to do something that cannot be done. The United States does not and never will possess the might to bend the people and powers of the world to our will. Hence we should not expend our blood and treasure attempting to do precisely that. The U.S. has interests, and it should defend them, with force when necessary. But those interests ought not to be defined so broadly that they extend to every corner of the globe, colliding with the far more powerful interests of those who actually live in those corners.

Either America will learn to act with realism and restraint on the world stage or it will further hasten its own decline in a foolish and futile effort to resist doing so.

There is no third alternative.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffs

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffsSpeed Read Six Republicans joined with Democrats to repeal the president’s tariffs

-

Bondi, Democrats clash over Epstein in hearing

Bondi, Democrats clash over Epstein in hearingSpeed Read Attorney General Pam Bondi ignored survivors of convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein and demanded that Democrats apologize to Trump

-

Are Big Tech firms the new tobacco companies?

Are Big Tech firms the new tobacco companies?Today’s Big Question Trial will determine if Meta, YouTube designed addictive products

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire

-

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by Russia

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by RussiaSpeed Read The ship was one of two vessels seized by the US military