When do stock market plunges really hurt the economy?

Here's when it's time to worry

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

America got a bear market for Christmas.

December was the worst month for the stock markets since the 2008 financial crisis. Christmas Eve 2018 was the worst single Christmas Eve the markets have ever seen. And while there was some recovery midweek, both the Dow Jones and the S&P have more than wiped out their gains for 2018, and are well on their way to wiping out their gains for 2017 too.

So how big of deal is it? Everyone instinctively treats a market plunge like this one as ominous news. But at the same time, there's no evidence of a downturn in fundamentals like hiring, quits, or wages. As many repeat ad nauseam, the stock market isn't the real economy.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

So let's get specific: When and how can a bear market hurt the real economy?

At bottom, the real economy's performance is all about aggregate demand. The more aggregate demand there is, the more jobs there are, and the higher and faster wages rise. Conversely, if a lot of aggregate demand suddenly goes away, jobs and wages disappear and you get a recession.

Generally speaking, what goes on in the stock market doesn't affect aggregate demand one way or the other. Investors mostly buy stocks and other instruments from each other; the money just gets traded back and forth within the financial markets, rather than actually going into new jobs or investments. When stock prices go up, it's investors, not companies, that make money. When stock prices go down, it's the investors, not the companies, that lose money.

The big exception here is initial public offerings (or IPOs). That's when companies create new stock and offer it for sale on the markets — that money does go into new investments, and thus new aggregate demand. Occasionally, enthusiasm in the stock market can get so out of control it drives a bunch of new IPOs. Then, when the bubble pops, all the aggregate demand generated by those new IPOs goes away.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The tech bubble is a good example of this.

In the late 1990s, just before the bubble burst, the number of new IPOs and the volume of money they raised shot way up. When the bull market changed into a bear market, all those new companies went up in smoke.

You can also see the tech bubble in private investment as an overall share of the economy. In the run-up to the 2001 recession, that percentage was almost as high as it had ever been.

Investment is one form of aggregate demand. So that was a sign that the stock market's behavior was bleeding into the real economy.

Another form of aggregate demand is consumer spending. A thing that can happen with an asset price bubble is that people feel wealthier, so they spend more. When the bubble pops, all that wealth goes away, and people spend less.

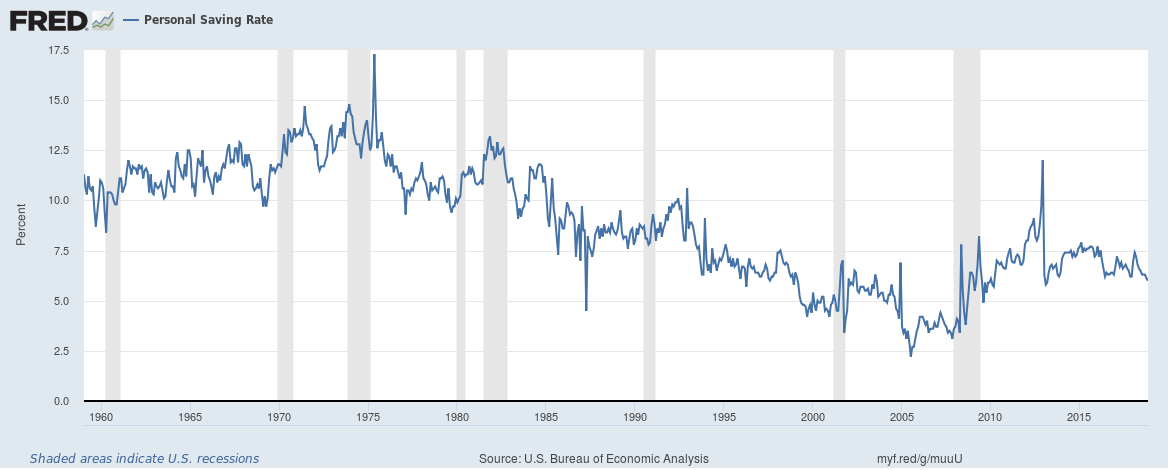

That arguably happened with the housing bubble in the 2000s. As housing prices went through the roof, people spent more — and the personal savings rate fell to its lowest level in decades. When 2008 arrived and those prices collapsed, lots of families fell into bankruptcy, which of course meant their spending collapsed. But even households that didn't suffer foreclosure still pulled back on their spending and saved more.

Of course, that rise in housing prices also encouraged an avalanche of bad mortgages. When all that debt went belly up, banks collapsed and the credit markets seized up, which ground business investment to a halt. Economists debate which of these two effects — the collapse in wealth or the collapse in credit markets — hurt aggregate demand more in the Great Recession. But both clearly mattered.

To sum up: Bear markets hurt the real economy when they move aggregate demand. They don't usually do that — we've had plenty of bear markets over the years. But sometimes there are big exceptions like 2001 or 2008.

The way to spot the exceptions is to look at all that data I just ran through.

For instance, as you can see from that initial graph, IPOs fell considerably after the 2001 tech bubble and have remained low since. The latest numbers for 2017 and 2018 don't suggest much of a change. As the second graph above shows, private investment as a share of GDP isn't especially high right now. In fact, it's about where it was at the bottom of the 2001 recession. It also hasn't precipitously fallen. The stock market doesn't appear to be moving aggregate demand this way either.

Finally, the personal savings rate has a slight downward trend to it, but it's been basically flat since 2013. It's still low by historical standards, but it isn't as bad as the 2000s. Stock market turmoil doesn't seem to be changing households' spending habits much, either.

Granted, there are looming threats on the horizon. The student debt load likely isn't big enough to tank the economy, but it can certainly crimp a lot of Americans' spending. The bigger threat is probably corporate debt, which could wreck investment if it causes a wave of business bankruptcies in the coming years.

As for the current bear market, it's certainly a problem for Wall Street investors — and for anyone with a stock portfolio. But it's not a threat to jobs or paychecks writ large.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.