A history of the southern border

Fences are a relatively new addition to the U.S.'s 1,954-mile boundary with Mexico

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Fences are a relatively new addition to the U.S.'s 1,954-mile boundary with Mexico. Here's everything you need to know:

How was the border established?

After the U.S. victory in the Mexican-American War in 1848, Mexico was forced to sign over 525,000 square miles of territory, including what is now California, Nevada, and Utah, as well as parts of Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Wyoming. Five years later, the U.S. purchased another 29,000-square-mile strip of land containing southern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico, more or less creating the present-day border. The sparsely populated region was barely policed, and Mexicans and Americans freely crossed back and forth. In border towns like Nogales, Ariz., saloons straddling the border sold Mexican cigars on the Mexican side and American liquor on the U.S. side to avoid customs duties. Illegal immigration wasn't considered a problem, because for most of the 19th century, the U.S. had virtually open borders. Would-be immigrants "didn't need a passport," said Mae Ngai, a historian at Columbia University. "You didn't need a visa."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

When did that change?

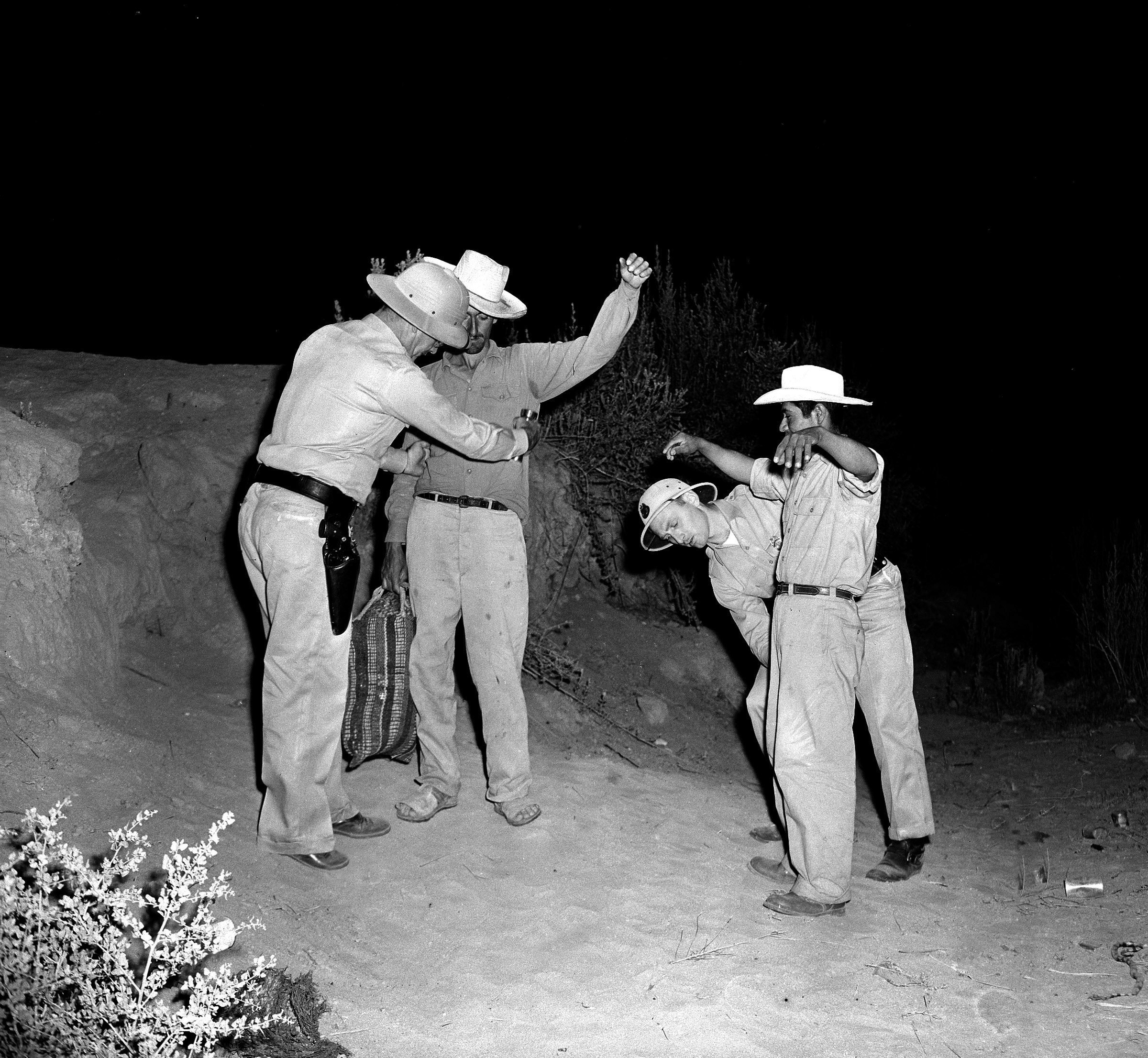

Congress passed the first major immigration restrictions in 1882, barring Chinese laborers from entering the U.S. Knowing they'd be turned back at official ports of entry, Chinese migrants began slipping over the southwestern border, sometimes learning a few words of Spanish so they could pass as Mexican. Congress created the Border Patrol in 1924 primarily to crack down on Chinese immigration and to stem the flow of illegal alcohol under Prohibition. Most of the illicit booze came through Canada, so the majority of early border agents were sent north. The southern border was lightly patrolled by a few hundred officers on horseback. Aside from a handful of private fences built during the Mexican Revolution of the 1910s, the boundary remained largely unfortified.

Why did security increase?

Because of a surge in Mexican immigration. During World War II, a temporary guest worker program was created to send Mexican laborers to manpower-starved American farms, and over the next 22 years some five million braceros would work in the U.S. That program ended in 1964, but the demand for cheap Mexican laborers did not. And when the Mexican economy slumped in the 1970s and early '80s, millions headed north without papers. By 1986, an estimated 3.2 million undocumented immigrants were living in the U.S., up from 540,000 in 1969. The War on Drugs, launched by President Richard Nixon in 1971, also focused attention on the southern border, which would become the main conduit for cocaine and marijuana.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What did the government do?

President Jimmy Carter's administration proposed the construction of a fence along the most heavily trafficked parts of the border in 1979, but scrapped the idea following a backlash at home and in Mexico. "You don't build a 9-foot fence along the border between two friendly nations," Carter's Republican rival, Ronald Reagan, said during the 1980 election. Still, Reagan would tighten border security as president. But rather than build physical barriers, he supported the passage of the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act, which boosted the Border Patrol's staff by 50 percent — to 5,000 personnel — and equipped agents with night-vision goggles, new helicopters, and high-tech surveillance systems. The law also provided amnesty and legal status to some 2.7 million undocumented immigrants.

When did the fences go up?

The first major physical barriers were constructed in the 1990s under Presidents George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton. They included a 14-mile-long fence separating San Diego and Tijuana, built using steel helicopter landing pads left over from the Vietnam War. The building spree intensified after the 9/11 attacks sparked fears of terrorists crossing the border: The Secure Fence Act, signed by President George W. Bush in 2006, added 548 miles of fencing at a cost of $2.3 billion. Another 137 additional miles of fencing were erected under President Barack Obama. Today, just over 700 miles of the border is fenced off.

Did the strategy work?

To a large degree. The fences have no doubt made it harder to cross the border, especially in populated areas. They're one reason 310,000 migrants were apprehended at the southern border in 2017, down from a peak of 1.6 million in 2000. Another major reason is that the number of Mexicans crossing illegally has declined as their country's economy has improved. But migration from gang violence–stricken Central America has tripled since 2007; such is the desperation of these people that fences have not deterred them, and most are now not evading border agents but legally applying for asylum. For that reason, many border experts doubt that more fencing will achieve President Trump's aim of deterring the most recent wave of undocumented immigrants. In addition, fencing does not address the reality that a majority of undocumented immigrants enter the U.S. legally and overstay their visas: There were an estimated 700,000 overstays in 2017. Border barriers will also do little to combat the illegal drug trade, because most narcotics are smuggled through legal checkpoints. Yet the wall remains a potent symbol. The border "is not just a line on a map," says Princeton University sociologist Douglas Massey. "In the American imagination, it has become a symbolic boundary between the U.S. and a threatening world."

The original border fence

The first federally funded border fence went up in 1911. But it wasn't built to keep people out. Instead, it was meant to stop tick-infested cattle from wandering into the U.S. The tick-borne disease "Texas fever" decimated herds on both sides of the southern border at the start of the century, driving up beef prices. While the disease was nearly eradicated in the U.S., it remained prevalent in Mexico. The Saturday Evening Post described the fence as "the finest barbed-wire boundary line in the history of the world," but it was only somewhat effective. The border region has since seen repeated outbreaks of Texas fever, including as recently as 2017. The U.S. Department of Agriculture still employs mounted "tick riders" to patrol the border for wandering cattle crossing over from Mexico. "As long as there's cattle across the river, or horses," said USDA inspector Jorge Solis, "we'll continue to have this problem."