Why Democrats need to talk about the national interest

Trump should not be allowed to claim the practical high ground simply because he has claimed the moral low ground

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It looks like the Democrats might have a foreign policy debate after all. Bernie Sanders radically shook up the party's domestic agenda with his 2016 run, to the point where large parts of his program have become mainstream. Now that he's entered the race for 2020, he is poised to challenge the conventional Democratic agenda on foreign policy as well — with potentially far-reaching consequences.

This is a very good thing indeed. Neither the Democratic Party nor the country have been well served historically by the Democrats presenting themselves as Republicans-lite, which has been their preferred stance more often than not since the Korean War. Fear of looking weak or accepting defeat caused that conflict to drag on for years until an armistice and for decades thereafter, sank America into the quagmire of Vietnam, gave George W. Bush strong bi-partisan support for the catastrophic Iraq War, and led Barack Obama to a smaller-scale repeat of his error in Libya.

But there's are two significant risks for the Democrats. The first is that they won't really have a debate. The second is that they will have it on the wrong terms.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The first risk seems quite likely based on how the campaign has proceeded so far. The dynamic of the 2020 race has featured an extraordinary degree of bandwagoning behavior. That's how much of the field could come to endorse Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez's Green New Deal essentially sight-unseen for fear of getting on the wrong side of progressive activists. Similarly, Kamala Harris endorsed reparations for slavery (a deeply unpopular policy) at the prompting of a radio talk-show host, and Elizabeth Warren jumped on board immediately after. Sanders isn't driving this bandwagoning — nobody is.

Since elections are more referenda on the incumbent than a fair comparison with the challenger, this stampede to the left won't necessarily prevent Democrats from winning. But the dynamic will make governing far more difficult, as the next president may not have built up the political capital to make his or her own decisions, and the party's activists will have come to expect fealty. In domestic policy, there are numerous choke points and restraints on presidential action, so the worst outcome from a governance perspective is simply failure to achieve desired goals. But a similar dynamic in foreign policy would be far more dangerous. Donald Trump has amply demonstrated the risks of having a president with fickle and idiosyncratic instincts and a lack of institutional support for changes of course.

The Democrats need to have a debate so that the winner has actually made a case for a particular direction in foreign policy, built up support for that case, and attracted advisors who share that view. Otherwise the instincts of the Blob will take over and overwhelm a weak presidency.

The second risk is that the terms of debate will be wrong, and will fail to grasp the nettle of the foreign policy choices before America. Stephen Wertheim in a recent New York Times piece articulated well what that debate should be: between those who see Great Power competition as the defining reality of our dawning era and those who see "realism and restraint" as the proper watchwords. This is the right debate because it starts from the right place: a recognition that the United States is no longer the global hegemon and the indispensable nation, that multipolarity, like climate change, is no longer a prediction but a present reality.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But will the Democrats have that debate? To do so, they'd have to be ready to talk primarily in terms of the national interest, because that is the grounds of the debate. Is it in America's interests to seek allies to confront and restrain China (for example), or are we better off husbanding our strength even if it means China's influence grows? Is it in America's interest to continue to underwrite collective security in Europe, or are we better off reducing our commitments there even if it means Russia's influence grows?

This is not the language that Democrats typically speak. Sanders, for all his radicalism, most often speaks a familiar moralized language of liberal internationalism. He favors a greater American commitment to international institutions and opposes American actions that have harmed other countries directly and bolstered reactionary forces around the world. This is certainly restraint — and there's a vital place for international institutions in preventing conflict and promoting cooperation. But it is not realism.

If he faces a debate, meanwhile, it may be with Joe Biden or whoever inherits his team of foreign policy advisors. But Biden is a largely unreconstructed believer in a benign American hegemony. A debate between Biden and Sanders could well revolve around whether American hegemony is good or bad, when in truth that hegemony is rapidly evaporating and the question is what should replace it.

Without the proper framing of the foreign policy questions we face, Democrats will have trouble building consensus around the right approach, even if they get one or another specific decision right. Consider the debate about Yemen. Sanders has distinguished himself by leading opposition to America's disgraceful support for Saudi Arabia's brutal war, and revivifying congressional involvement in foreign affairs. But the reason we're in Yemen in the first place is that the Obama administration wanted to mollify Saudi anger about the nuclear deal with Iran and reassure them that we still supported their efforts to limit Iranian influence. The war, in other words, was a matter of realpolitik.

The Trump administration, of course, abandoned the Iran deal, and has hugged Saudi Arabia even closer, reflecting its own conception of realpolitik. But other than being a valuable market for American arms exports, it's unclear how the Saudi relationship actually benefits the United States. Indeed, with America approaching independence in petroleum products, and with decarbonization a vital goal for Americans threatened by climate change, how does it make any sense for the United States to spend money, blood, and influence making sure China (Saudi Arabia's largest customer) has access to cheap Saudi oil?

There's a good case to be made from both a Great Power competition perspective and from the perspective of realism and restraint that the relationship with Saudi Arabia is harming rather than helping American interests. Trump should not be allowed to claim the practical high ground simply because he has claimed the moral low ground. But taking him on means accepting his premise that not all alliances are in American interests.

Or consider North Korea, where the Trump administration has veered from rhetorical belligerence to eagerness for a deal on terms highly favorable to the North. North Korea is one of the most brutal regimes on Earth, has amassed an impressive arsenal of atomic weapons and missile delivery systems including ICBMs, and has shown a willingness in the past to facilitate their proliferation. Moralists, in this case, are on the side of continued confrontation and are joined by advocates of American primacy who fear the consequences of allowing North Korea to keep its arsenal (as it almost certainly will).

But it's not clear how America benefits from a policy of confrontation, which has utterly failed to prevent North Korea from building the military capabilities we find so threatening. On the contrary, it is arguably America who is most held hostage by the current arrangements. Former National Security Advisor Susan Rice's recent op-ed illustrates well the consequences for America's diplomatic posture; she's reduced to complaining that our allies are pursuing their own interests rather than keeping a united front in a situation where, ostensibly, their security is the reason we are engaged in the first place. An end to the Korean War and normalization could be beneficial not only because peace is better than war (which it is) but because it could extricate America from a position where we define our interests in the region largely in terms of preserving our own indispensability. An end to the Korean War and normalization could be beneficial not only because peace is better than war (which it is) but because it could extricate America from a position where we define our interests in the region largely in terms of preserving our own indispensability.

The temptation will be strong for Democrats to oppose essentially anything Trump does on the grounds that it is immoral, corrupt, or too risky or all three. And in many cases they will be right, even when (as in the case of North Korea) there is also something to be commended. But opposition is not a governing strategy.

America's national interests are not identical to the interests of the foreign policy establishment (who benefit from America's far-flung quasi-empire), nor to the interests of American corporations, whether they are oil companies or arms manufacturers or Hollywood studios. But that doesn't mean they don't exist or that they are somehow tainted as such for being "national." On the contrary, if the Democrats want not only to win but to lead, they need to articulate a foreign policy perspective that is grounded in America's national interests. Which means having a real debate now about what those interests are.

Noah Millman is a screenwriter and filmmaker, a political columnist and a critic. From 2012 through 2017 he was a senior editor and featured blogger at The American Conservative. His work has also appeared in The New York Times Book Review, Politico, USA Today, The New Republic, The Weekly Standard, Foreign Policy, Modern Age, First Things, and the Jewish Review of Books, among other publications. Noah lives in Brooklyn with his wife and son.

-

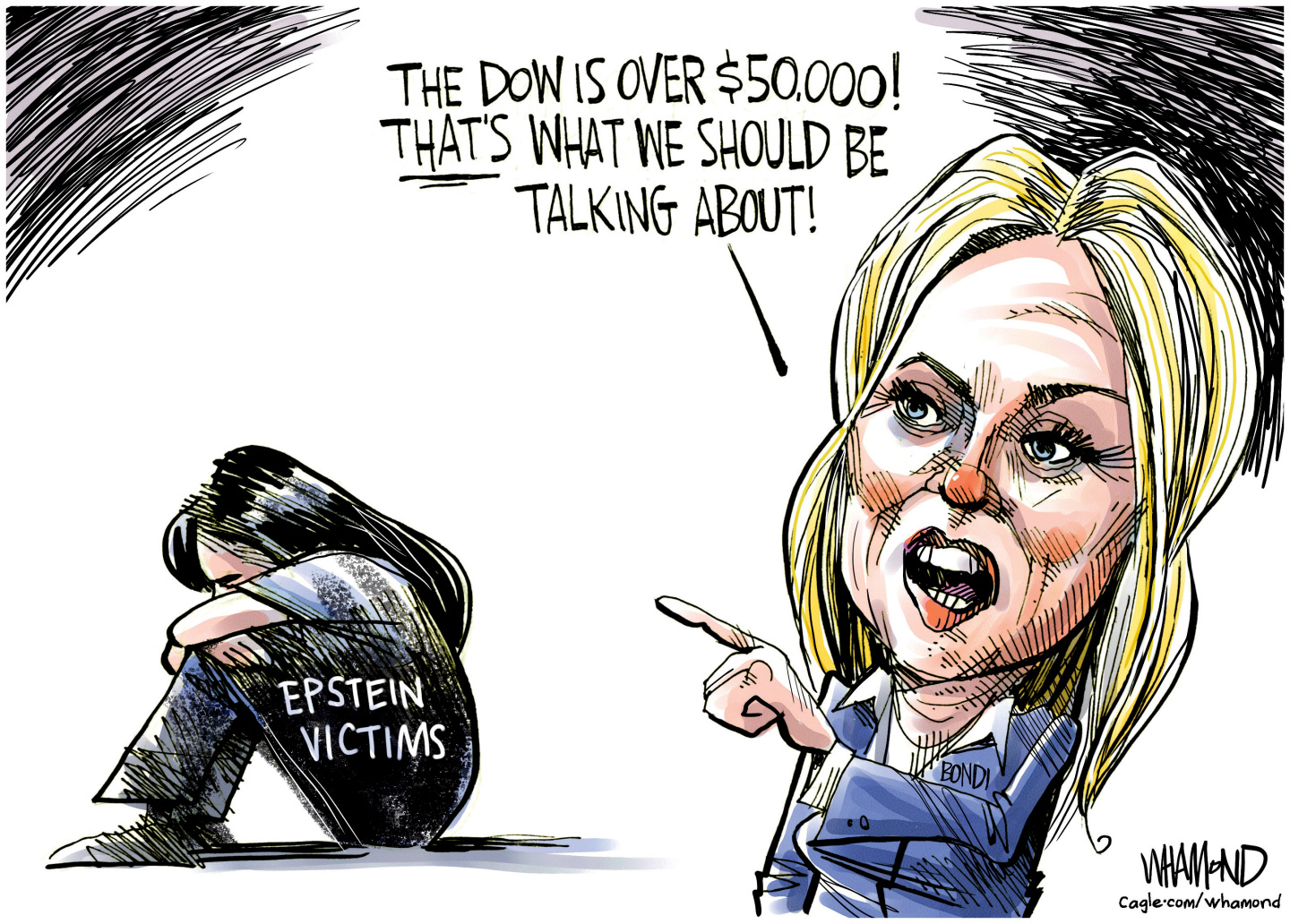

Political cartoons for February 12

Political cartoons for February 12Cartoons Thursday's political cartoons include a Pam Bondi performance, Ghislaine Maxwell on tour, and ICE detention facilities

-

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ return

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ returnThe Week Recommends Carrie Cracknell’s revival at the Old Vic ‘grips like a thriller’

-

My Father’s Shadow: a ‘magically nimble’ film

My Father’s Shadow: a ‘magically nimble’ filmThe Week Recommends Akinola Davies Jr’s touching and ‘tender’ tale of two brothers in 1990s Nigeria

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred