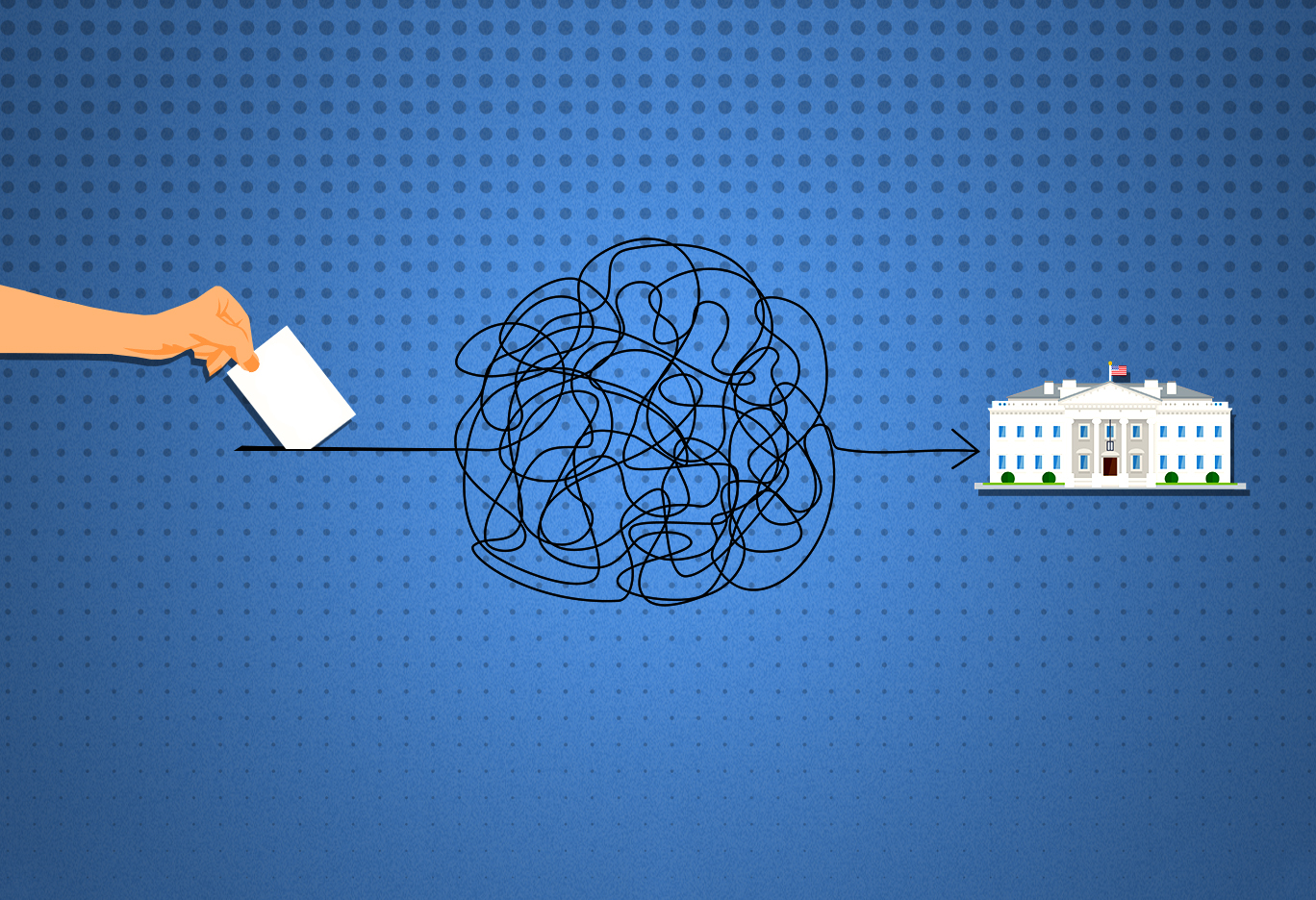

Debunking the most common defenses of the Electoral College

Would getting rid of it really be so bad?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The sometimes-hot, sometimes-cold argument about the Electoral College is hot again thanks to Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), the Democratic presidential candidate who seems intent on subduing her rivals with the sheer quantity of her policy proposals.

Her latest idea? Get rid of the Electoral College and instead elect the president of the United States directly, via a national popular vote.

"Every vote matters," Warren told a Mississippi audience this week, "and the way we can make that happen is that we can have national voting, and that means get rid of the Electoral College."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The proposal, The New York Times reported, drew "one of her longest ovations of the night."

No wonder. Democrats — stung by winning the popular vote twice in 16 years only to lose the White House thanks to Electoral College votes — have been advancing variations of this argument with greater intensity since Donald Trump became president. The reasoning is plain enough: In most campaigns, the candidate who wins the most votes wins the office. It's perhaps the most fundamental idea of a democracy: majority rules. In America, the presidency seems to be the only real exception to this rule.

Defenders of the Electoral College have painted Democrats as sore losers, and there's probably something to that. But that might be their best argument for keeping the status quo — and it's not enough. Let's examine four common defenses of the Electoral College:

1. The Founders intended the Electoral College to restrain the popular will.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"It wasn't meant to be democratic," Jarrett Stepman wrote this week for Fox News. "Pure democracies, as the founders knew from studying history, typically ended in mob rule, violence, and tyranny."

This is only half true. The Founders weren't unvarnished small-d democrats. But a close examination of their writings suggests that while they didn't want the majority to run roughshod over the rights of the minority, they also feared allowing minority factions to subvert the will of the majority. James Madison, in particular, used the Federalist Papers to warn against government structures that would allow minority factions to subvert the popular will.

In such cases, Madison wrote in Federalist 58, "the fundamental principle of free government would be reversed. It would be no longer the majority that would rule: the power would be transferred to the minority." The countermajoritarian argument for the Electoral College suggests that violating such a "fundamental principle" is somehow virtuous. It's not.

2. Smaller states will be ignored by presidential campaigns.

"What Democrats want is effectively to make California and New York the kingmakers in presidential politics, and not have to bother with the middle of country and smaller, more rural states," Rich Lowry wrote at Politico. "This is exactly the approach that the Electoral College is meant to foreclose, in favor of greater geographic diversity."

In that case, the Electoral College is failing. As the folks at National Popular Vote point out, two-thirds of general election campaign events in 2016 were held in just six states — Florida, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Virginia, and Michigan — and 94 percent of them were held in just 12 states. The campaign to govern the country is already being contested on fairly narrow grounds, and almost never in smaller, more rural states.

A national popular vote, though, might force smart campaigns to mount Moneyball-style campaigns that target underserved, previously ignored voters. As the author Sarah Smarsh pointed out last year, so-called "red states" are not completely red: "Among the 30 states tidily declared 'red' after the 2016 election," Smarsh wrote, "in two-thirds of them Mrs. Clinton received 35 to 48 percent of the vote." Put those voters up for grabs, and candidates would be forced to expand their maps.

3. Democrats criticize Trump for breaking norms, but now they're willing to dispense with this tradition? What hypocrites!

"On the one hand, Democrats have made 'restoring norms' a cornerstone of their campaign to remove Trump from office," Andrew Stiles wrote at The Washington Free Beacon, later adding: "When it comes to seizing and holding power, Democrats appear all too ready to scuttle the norms that stand in their way."

Let's be clear: Sometimes it is good to move on from outdated traditions and norms. There's a real difference between Trumpist norm-smashing — which has left a trail of damaged institutions in its wake, giving way to the president's own impulses and whims — and the proposals to alter or eliminate the Electoral College. Whether it's through a Constitutional amendment or through the National Popular Vote effort, such changes will come about only with the considered backing of many voters and many states.

That leads to what is probably the most powerful argument Electoral College defenders are making:

4. Changes aren't coming soon — if at all — so why bother?

If we've learned one thing from the past decade or two of American politics, though, it's how fast the Overton Window can shift. For years, Democratic politicians refused to support gay marriage — until, suddenly, they did. Socialism, democratic or otherwise, was once condemned to the fringe of discourse, but that's no longer the case. So let's start the conversation and keep it going. Given time, defenders of the Electoral College might even come up with better arguments.

Joel Mathis is a writer with 30 years of newspaper and online journalism experience. His work also regularly appears in National Geographic and The Kansas City Star. His awards include best online commentary at the Online News Association and (twice) at the City and Regional Magazine Association.

-

Minnesota's legal system buckles under Trump's ICE surge

Minnesota's legal system buckles under Trump's ICE surgeIN THE SPOTLIGHT Mass arrests and chaotic administration have pushed Twin Cities courts to the brink as lawyers and judges alike struggle to keep pace with ICE’s activity

-

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire tax

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire taxTalking Points Californians worth more than $1.1 billion would pay a one-time 5% tax

-

‘The West needs people’

‘The West needs people’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Could Trump run for a third term?

Could Trump run for a third term?The Explainer Constitutional amendment limits US presidents to two terms, but Trump diehards claim there is a loophole

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration