Moving federal agencies out of D.C. is a good idea

Why a much-maligned Trump administration plan may not be so bad

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The Trump administration is relocating two major Department of Agriculture research agencies from Washington, D.C., to Kansas City. Neither Democrats nor the agencies' own employees are happy about it.

The Economic Research Service, as its name suggests, does research and analysis for policymakers, while the National Institute of Food and Agriculture provides federal funding for research. Last Thursday, when Trump-appointed Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue announced their relocation, employees at both agencies stood up and turned their backs on Perdue to protest the move. Congressional Democrats lambasted the idea as well, and a group of Democratic senators have even introduced a bill to scuttle Perdue's plan.

Honestly, though? While it would obviously be a difficult disruption to the lives of current employees, the general idea is a pretty good one. At the very least, even if moving these two specific agencies isn't advisable, moving a large portion of the federal apparatus out of D.C. and distributing it across the country is worth serious consideration.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Admittedly, whether you trust this particular White House to carry out the process with effectiveness and integrity is another question entirely. The Trump administration has been on a nihilistic (and brazenly hypocritical) quest to "drain the swamp." It's tried to squash federal research on subjects like climate change — a topic touched on by the work of both of the affected agencies — that clash with Trump's preferred talking points.

The bad blood has also clearly had an effect. Kevin Hunt, the acting vice president of the Economic Research Service union, said Perdue's plan "highlights disregard for the rights and well-being of employees." Agency employees and their representatives tell reporters they think the gambit is a veiled strategy to slash staff and silence research the administration finds politically inconvenient. The plan would relocate around 550 positions, and employees say material support for them in the move has been hazy and inadequate. The agencies' morale was also already hit hard by the recent Trump-driven government shutdown.

Right-wing Republicans even have a bill that proposes to take Perdue's proposal and expand it to the entire federal government: The "Drain the Swamp Act" would push 90 percent of federal employees out of the district and distribute them across the country by 2023. With a name like that, you can hardly blame people for seeing it as culture war by other means.

Yet it's an idea that some on the left also endorse. "The government needs to empower different kinds of places," David Fontana, a Democrat and a George Washington University law professor, told the Washingtonian's Benjamin Wofford, "in order to harness different kinds of people." Fontana said he doesn't agree with the bill's specific numbers and plans — he thinks the most important thing would be to spread out agency leadership — but that the general idea might achieve the exact opposite of the Trumpian desire to desiccate the government. "[Fontana's argument] visualizes power as a kind of national resource, something to be distributed equitably," Wofford wrote. "Not unlike Medicare, access to a national resource such as federal power might buttress voters' confidence in government. Rather than starving the beast, Americans might come to embrace it."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Now, the greater metropolitan area around Washington, D.C., accounts for 22 percent of the federal workforce, and the rest is already spread across the country. Which might make it seem like the job is already done — until you consider that same metropolitan area accounts for less than two percent of the national population. Moreover, census data shows that some of the neighborhoods in the district's broader scope are among the very richest in America. No less than one quarter of the region's jobs are either provided directly by the federal government, or by contractors who enjoy federal funding.

Republicans and conservatives view this as evidence of the government's parasitism on the rest of the country. But they're wrong: It's evidence of the federal government's unique fiscal and monetary powers — its ability to invest in the public and create jobs regardless of how well the surrounding private economy is or isn't doing. Shouldn't that ability be as equitably distributed across the country as possible, so the incomes and investment it brings can lift more places up?

Vox's left technocrat Matt Yglesias made a similar pitch not too long ago: A lot of cities out there, especially in the Midwest, have the educational and infrastructural resources to support a skilled and productive federal agency workforce. But they're also slowly bleeding jobs and people, as America's increasingly vertiginous regional inequality sucks all those resources to a few key urban hubs like San Francisco, D.C., and New York. Spreading out federal agencies would give these "second tier" cities a boost. This would drain D.C. of jobs and people, but it would also slow the relentless march of the district's already sky-high costs of living, and the inevitable gentrification and local segregation that comes with that.

Richard Florida, one of the country's premier center-left theorists on urban studies, is also in favor of some version of the idea, for all the same general reasons.

Finally, to be perfectly blunt about it: Yes, Washington, D.C. is a cultural, ideological, and socioeconomic bubble. More and more Americans not only congregate with people of similar wealth and income levels, but with people of similar values and politics and culture as well. Read through some Democratic senators' reactions to Perdue's plan, and you'll catch the unspoken implication that D.C. is an important place, while Kansas City (and other possible locations) aren't. And how could federal workers be expected to do worthwhile things in unimportant places?

Precisely because the federal government does not have to play by the same economic rules as private businesses, it's well-positioned to push back against this trend. And it would benefit our politics if U.S. policy was conceived and executed in one of the most intensely concentrated hothouses of America's interior balkanization.

None of this means the idea is perfect, however. There are real concerns with how effectively federal agencies can collaborate and communicate if they aren't in geographic proximity. What places get what agency can become hopelessly politicized. And uprooting human beings and their families from the places they work is always tough and fraught. Wofford's Washingtonian piece is worth reading, as a fair and even walk-through of all of this.

But at a minimum, pulling a lot more of the federal apparatus out of D.C. and depositing it across America is an idea believers in government as a force for good should take seriously.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

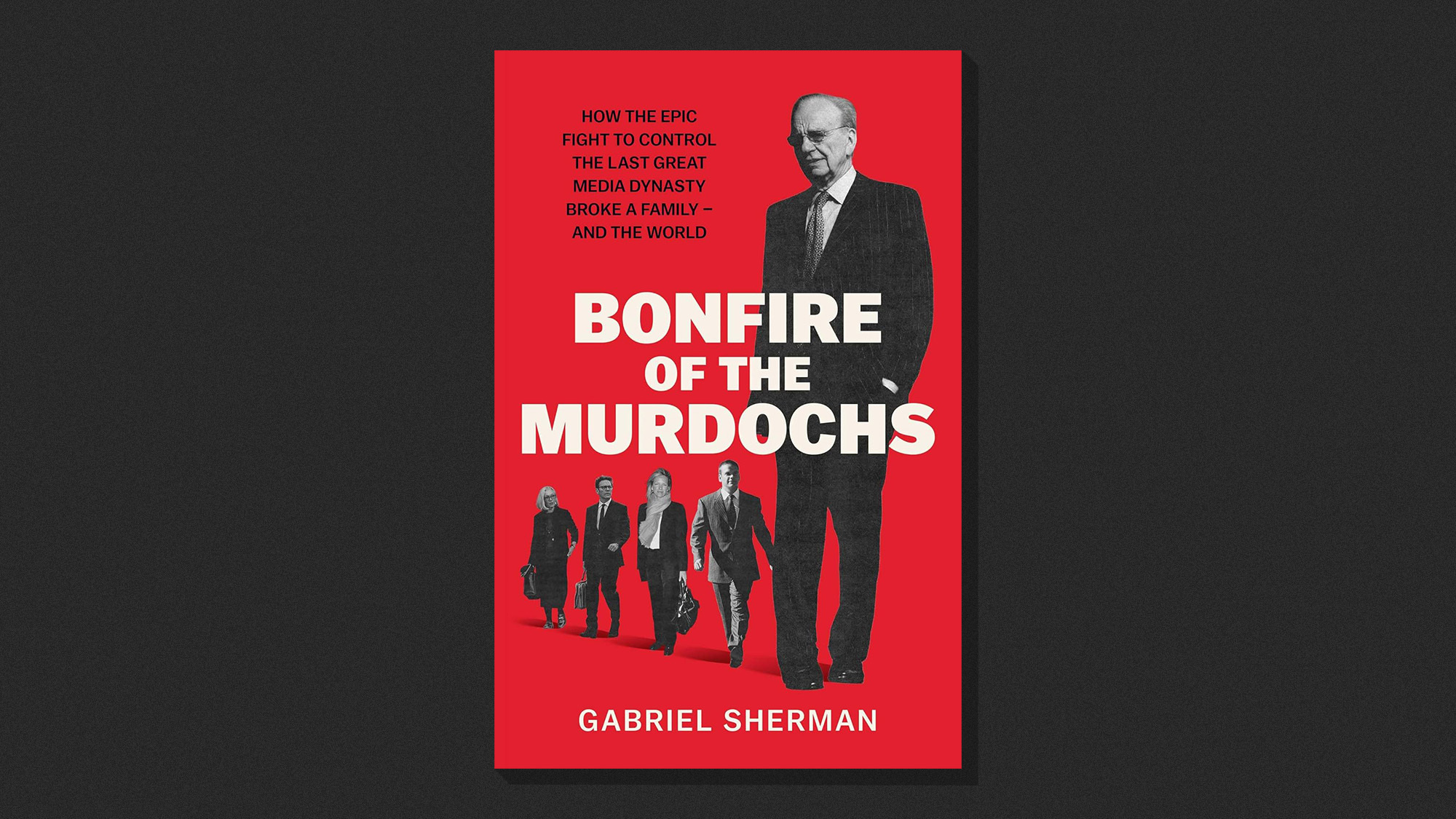

Bonfire of the Murdochs: an ‘utterly gripping’ book

Bonfire of the Murdochs: an ‘utterly gripping’ bookThe Week Recommends Gabriel Sherman examines Rupert Murdoch’s ‘war of succession’ over his media empire

-

Gwen John: Strange Beauties – a ‘superb’ retrospective

Gwen John: Strange Beauties – a ‘superb’ retrospectiveThe Week Recommends ‘Daunting’ show at the National Museum Cardiff plunges viewers into the Welsh artist’s ‘spiritual, austere existence’

-

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?Today's Big Question After rushing to praise the initiative European leaders are now alarmed

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred