How our government is killing growth

The real lesson of the latest lousy GDP numbers is that American government has utterly failed to spend its way out of this economic downturn

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

America got some sobering news on Friday: The economy shrank in the first quarter of 2015.

A lot went into the 0.7 percent drop in gross domestic product (GDP). There was a bigger-than-expected fall-off in exports, low oil prices, and even the possibility that the data-crunchers didn't accurately adjust for winter weather. (Though if the data-crunchers didn't sufficiently revise the first quarter numbers up, that also means they didn't sufficiently revise all the other quarters down.) But more broadly, the decline is a reminder that seven years after the 2008 collapse, the economy still refuses to achieve a real liftoff. Even Justin Wolfers, who made the best version of the it's-just-a-statistical-hiccup case, called it an argument for "reduced pessimism" as opposed to optimism.

This is an opportune time to remind everyone that we Americans possess a remarkable invention that can boost wages, pump up demand, repair the economy's capacities, and give people jobs. We even have a name for this miraculous device: "government."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Government spending and hiring can serve as a kind of guaranteed supply of economic activity, regardless of how the rest of the market shifts and expands or contracts around it. Every dollar the government spends on the safety net, on purchasing goods, on hiring contractors, or on paying its own workers is a dollar that can then recirculate through the economy as the people who got it go and spend it in various parts of the private sector. The government provides a kind of floor or ballast for the rest of the economy.

There's always important stuff the government can be doing; it's not as if Americans' needs for things like education, health care, or good roads goes up and down with the markets. Furthermore, the degree to which government is providing public services like that is the degree to which those services aren't a drag on household budgets during recoveries.

Up to a point, government can also provide a certain amount of employment opportunity, so people don't lose skills, professional networks, or even less concrete things like hope and a sense of purpose. The percentage of Americans who have been without a job for six months or more is still, seven years after the recession, nearly as high as it's ever been in the last half century. And remember, public sector jobs, which the government can create whenever it wants, have long been a route to the middle class for minorities like African-Americans who have historically been oppressed in, and marginalized from, other sectors of the economy.

So why isn't our miraculous, economy-boosting device called "government" actually boosting the economy? Because following the 2008 crisis, the government in this country did something unprecedented in any recession since at least the 1960s: American policymakers chose to cut spending and hiring to such a degree that it's actually dragged down the economy.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

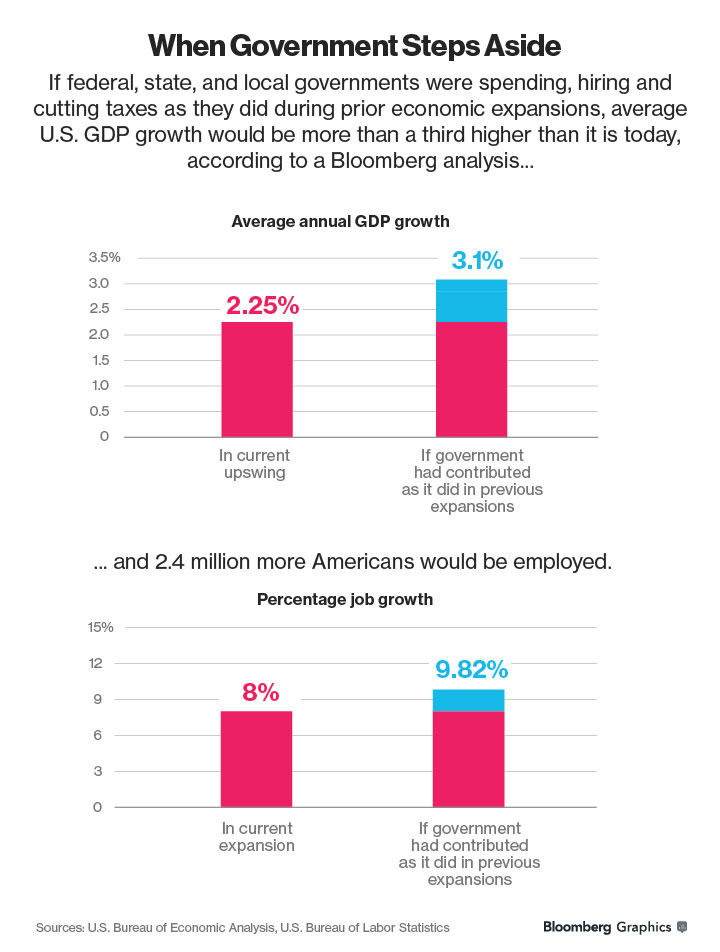

Peter Gosselin hashed out the numbers at Bloomberg Business, showing austerity has reduced job growth since 2009 by 6.4 percent, and GDP growth by 0.23 percent. Had local, state, and federal government kept to their track record from previous recoveries, average annual GDP growth would be 3.1 percent as opposed to 2.25 percent, and the total amount of jobs would've grown by 9.8 percent instead of 8 percent.

That would have translated into 2.4 million more Americans with jobs — or an unemployment rate of 3.9 percent instead of the 5.4 percent we have.

The failure has occurred at all levels of government: The feds reacted relatively well to the Great Recession with the 2009 stimulus, but that boost to the economy was soon overtaken by cuts at the state level. Then Republicans won control of the House in 2010, forcing a negotiated set of cuts to federal spending. So austerity took hold at the national level as well.

Now, you can't have government account for 100 percent of GDP. Its centralized planning is fundamentally different from the decentralized experimentation that characterizes private free markets, and both forms of economic activity have their strengths and weaknesses. (Though it's worth noting that taxes levied by all levels of government combined — local, state and national — are considerably higher in other Western countries than in the U.S., with no noticeable effect on economic health.) Critics of government make the perfectly sound point that the public share of the economy can get too big. That is absolutely valid. But often, they twist this point into an insistence that government can never be too small. That's how we got the austerity craze and cuts in public investment, services, and aid.

This is particularly frustrating given the way the federal government is uniquely positioned to counter economic downturns. Slumps almost always result in flights by investors into the safe haven of bonds, which reduces government borrowing costs, so interest rates on federal debt remain incredibly low. And even in normal circumstances, the federal government's ability to print money gives it a unique power to borrow and spend at exceptionally low cost, which it could in turn use to shore up finances at the state and local levels.

It's true that enough government borrowing and printing can drive up inflation, and that government spending can simply crowd out private sector spending and investment rather than building atop it. But these risks only hold when the economy is running at full capacity; when all the factories and equipment and workers and so forth that could be put to work are being put to work. Needless to say, we have been nowhere near full capacity since the 2008 collapse. In fact, full capacity has been rather hard to come by for the last few decades.

On top of that, the state of U.S. infrastructure, roads, and public transit, while not a disaster, is hardly stellar. We have government agencies that are so understaffed they can no longer do their jobs efficiently or accurately. We even have a whole city — Detroit — where public services are literally shutting down, even as a large portion of the population is desperate for work. There's clearly an enormous amount of useful stuff the federal government could be doing, if U.S. policymakers were willing to fire up the spending, hiring, and borrowing powers again.

But they're not. And the ultimate scandal is that no one seems scandalized by this.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

The environmental cost of GLP-1s

The environmental cost of GLP-1sThe explainer Producing the drugs is a dirty process

-

Greenland’s capital becomes ground zero for the country’s diplomatic straits

Greenland’s capital becomes ground zero for the country’s diplomatic straitsIN THE SPOTLIGHT A flurry of new consular activity in Nuuk shows how important Greenland has become to Europeans’ anxiety about American imperialism

-

‘This is something that happens all too often’

‘This is something that happens all too often’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred