Democrats are in denial about 2020

Running to the left on everything won't win the Electoral College

A consensus has recently formed among such centrist columnists as Andrew Sullivan, David Brooks, and Bret Stephens that the Democratic Party's leftward lurch — proudly on display at last week's inaugural two-part debate — spells serious electoral trouble ahead. An equally solid consensus has formed among progressives that such worries are thoroughly misplaced — merely an expression of the pundit's fallacy that a candidate's electoral success is directly correlated to his or her embrace of the writer's personal policy preferences.

Too bad this isn't what these columnists are saying — or what's really at stake in the Democratic Party's ongoing ideological transformation.

The Democratic Party is responding in a nonsensical way to political reality. As luck would have it, we were reminded of the character of this reality on the very morning of the second debate, when the Supreme Court announced its 5-4 decision in Rucho v. Common Cause, which takes federal courts out of the business of policing partisan gerrymanders. If Democrats don't like district lines that make it prohibitively difficult for them to win elections in GOP-controlled states (which significantly outnumber Democrat-controlled states), they now have no option but to … win majority control for themselves, regardless of the obstacles manufactured by Republicans.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Democrats confront numerous disadvantages in our electoral system. House districts can be gerrymandered by Republican-controlled state legislatures to give conservatives an advantage in their efforts to win and hold a majority. The Senate favors low-population-density states at a time when progressives increasingly cluster in urban areas. The Electoral College likewise inflates the representation of low-population states, giving a substantial edge to Republican presidential candidates. And the Supreme Court oversees it all, with its lifetime appointees nominated and confirmed by the GOP-advantaged president and Senate.

Put it all together and Democrats face what increasingly looks like a system rigged to thwart or at least seriously dilute their political power.

The question is how to respond — and that's where the Democrats are going off the rails.

This wasn't the case in 2018. Heading into the midterm elections, the party deployed a politically wise divide-and-conquer strategy. In homogeneously liberal areas (like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez's district in New York City), strong progressives ran and sometimes won impressive victories. But in more moderate districts and states, more centrist candidates ran and also did well. The result was a solid set of victories for the party that many on the left have taken to be a very encouraging indication of its prospects against Trump in 2020.

But in a presidential race, a party can't divide and conquer. Only one ticket will go up against Donald Trump and Mike Pence in 2020 — and in an almost comically large early field, most of the Democratic candidates are running as progressives. And they're not just running to the left of the party's recent positions on some issues while staking out more moderate stances in other areas. Most of the candidates are running as progressives on everything at once: health care, immigration, taxes, child care, college loans, abortion, guns, transgender rights, and on and on.

If the structural problems confronting the party didn't exist, this might make sense. Democrats could just try to run up the vote in the country's biggest and most liberal cities on the rationale that more votes is more votes, no matter where they come from.

But of course this isn't the way the game is played in the United States. To win the presidency, Democrats still need to prevail in states where the population isn't very progressive — or where it might be potentially progressive in some areas of policy (health care) but not in others (abortion, immigration, guns). Denying this fact won't make it go away.

That progressives have ended up in this position just two and a half years after Hillary Clinton won the popular vote by three million and yet still lost to Trump is astonishing. (You wouldn't know it from listening to Bernie Sanders supporters, but Clinton ran a strongly progressive campaign in 2016.) A big factor in that lopsided popular-vote outcome was California, where Clinton beat Trump by 4.3 million votes, 61 percent to 31 percent. Listening to the leading candidates on stage last week, it sounded at times like their main electoral goal is to win California with 80 percent next time around and so prevail in the national popular vote by something more like five million.

That would be an impressive achievement for the Democrats. But they would still lose the presidency — and might also lose the Senate as well.

Progressives are so utterly convinced of the injustice of this political reality that in reaction to it they've driven themselves to embrace two forms of denial. One form of denial has them living inside a fantasy of changing the system from top to bottom. They'll break liberal California into multiple new states and grant statehood to Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico in order to take firm control of the Senate. They'll abolish the Electoral College so the president is determined by a nation-wide popular vote. They'll pack the Supreme Court to ensure no part of the federal government pushes back against these and other efforts at radical institutional reform.

The problem with this fantasy is that it requires winning first, using the current rules — and talking about wanting to make such radical changes will make such a victory less likely. Then there's the scenario in which progressives manage to take control in 2020 and set out to make these changes regardless of whether they campaigned on them. The result would almost certainly be a right-wing backlash that would make the post-ObamaCare tidal wave midterm election of 2010 look like a minor ripple in a wading pool.

The other form of denial to which today's Democrats are prone has them dreaming about magically overcoming their problems, not by responding reasonably to the demands of the electoral map (by moderating their positions on some issues), but by embracing their inner democratic socialist. They hope and pray, in other words, that if they pretend their structural problems don't exist, they'll be rescued by demographic trends or Trump's awfulness or their own charm and charisma or the latent leftist convictions buried deep within the American electorate.

None of that is likely to be true. The Democratic shift to the left in absolutely every area of policy at once may or may not motivate ever-more people to vote for them — but it's quite unlikely to help them carry more states. Which means it's unlikely to get them a victory in the actual election they need to win.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

6 peaceful homes near small towns

6 peaceful homes near small townsFeature Featuring doors with local topographical maps in Oregon and a 1850s homestead-turned-house in Vermont

-

What would happen to Earth if humans went extinct?

What would happen to Earth if humans went extinct?The Explainer Human extinction would potentially give rise to new species and climates

-

The best TV shows based on movies

The best TV shows based on moviesThe Week Recommends A handful of shows avoid derivative storytelling and craft bold narrative expansions

-

Grijalva wins Democratic special primary for Arizona

Grijalva wins Democratic special primary for ArizonaSpeed Read She will go up against Republican nominee Daniel Butierez to fill the US House seat her father held until his death earlier this year

-

A Democratic election in Arizona is a microcosm of the party's infighting

A Democratic election in Arizona is a microcosm of the party's infightingThe Explainer The top three candidates are fighting it out for a special election seat

-

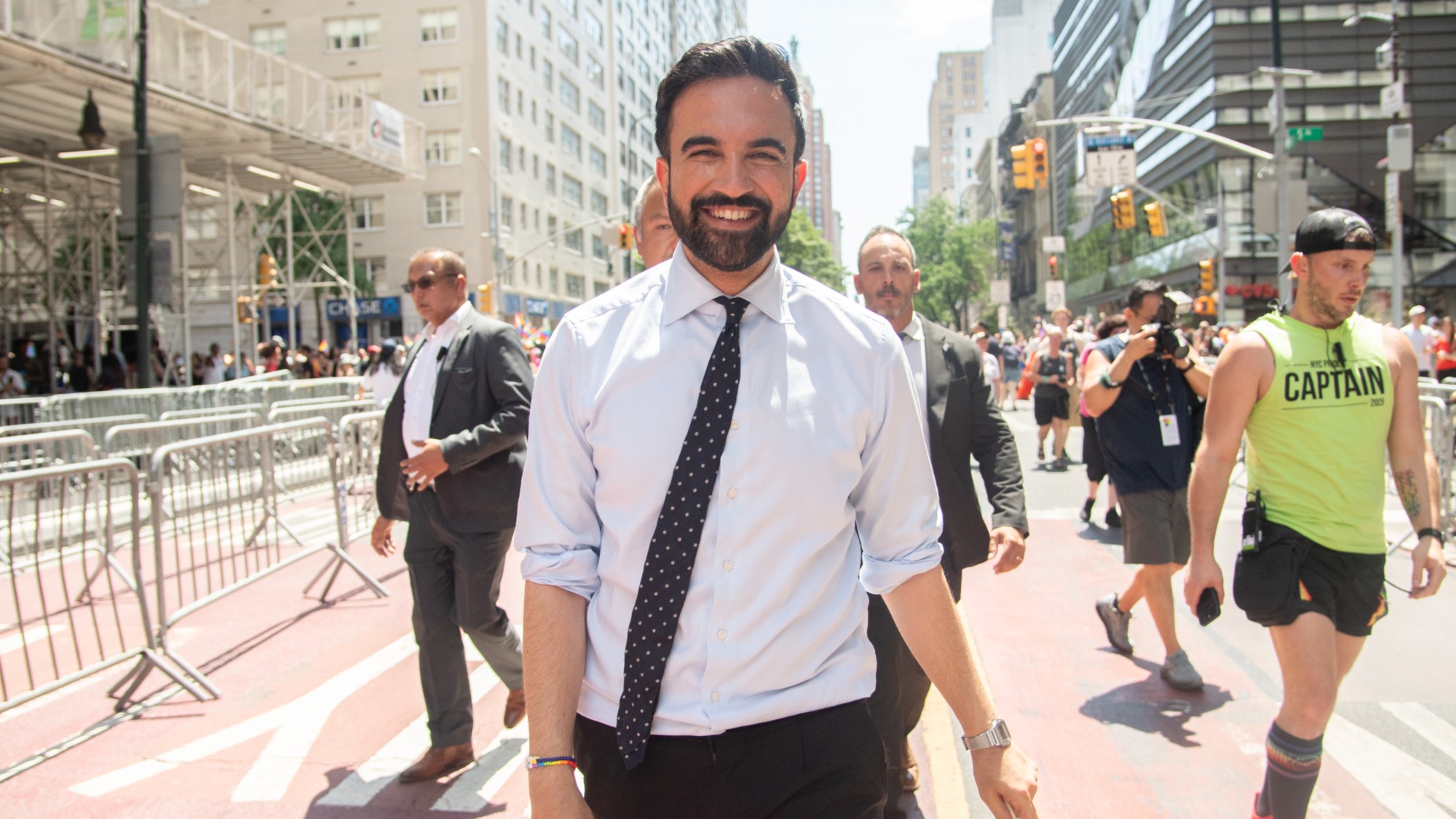

Zohran Mamdani: the young progressive likely to be New York City's next mayor

Zohran Mamdani: the young progressive likely to be New York City's next mayorIn The Spotlight The policies and experience that led to his meteoric rise

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

Some mainstream Democrats struggle with Zohran Mamdani's surprise win

Some mainstream Democrats struggle with Zohran Mamdani's surprise winTALKING POINT To embrace or not embrace? A party in transition grapples with a rising star ready to buck political norms and energize a new generation.

-

DNC rocked by high-profile departures as future is in question

DNC rocked by high-profile departures as future is in questionIN THE SPOTLIGHT Generational shifts, ambiguous priorities, and the intensifying dangers of the Trump administration have pushed the organization into uncertain territory

-

Trump tells ICE to hit blue cities, spare farms, hotels

Trump tells ICE to hit blue cities, spare farms, hotelsSpeed Read Trump has targeted New York City, Chicago and Los Angeles among other cities

-

'It was also a gift to music-lovers'

'It was also a gift to music-lovers'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day