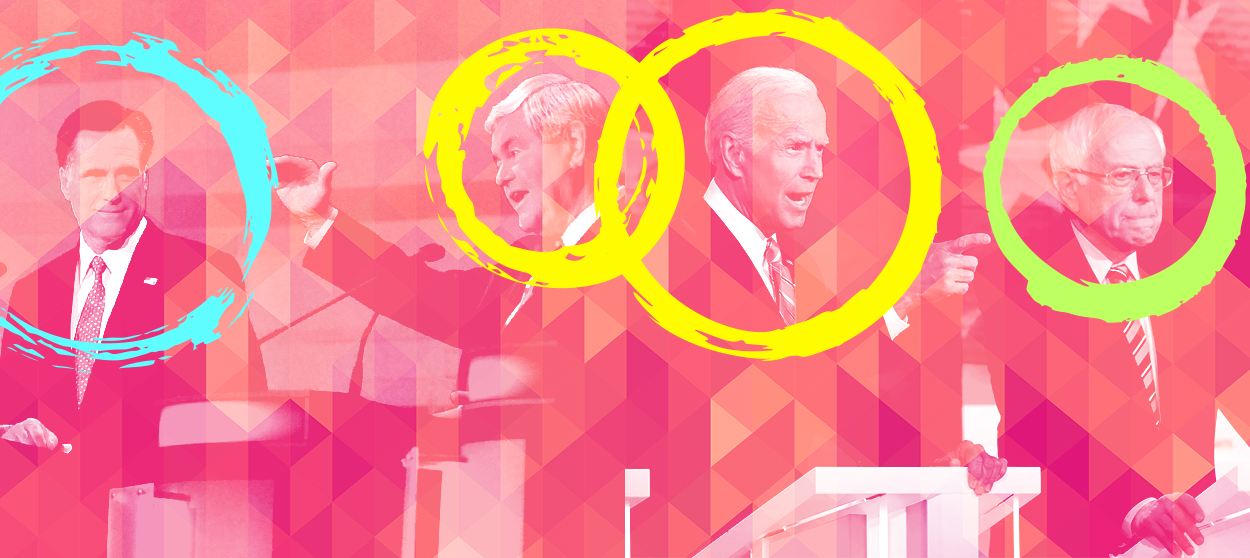

We've seen the 2020 Democratic primary before

Lessons from the 2012 Republicans

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

"Happy families," Tolstoy wrote, "are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way." For years I have wondered whether a version of this dictum might be applied to presidential elections.

Pretending that there are ever direct one-to-one correspondences between different election cycles is a mug's game. But that doesn't mean that there is nothing to be gleaned from past campaigns. In many ways the election that 2020 resembles most is the contest between Barack Obama and Mitt Romney in 2012, in which an incumbent who had begun to lose his hold over independent voters triumphed over what passed for an ideological moderate from the opposition party, who had survived an intemperate primary.

It is certainly more relevant than the 2016 campaign, and not just because the latter did not feature an incumbent. I would hesitate to call our last election a "contest of ideas," but Donald Trump's candidacy did force all of the other Republican hopefuls to put aside their pocket Declarations of Independence and talk about other things — himself most of all. This would prove to be fatal to his fellow GOP challengers, and to Hillary Clinton, who ended up running in the general election against Trump and in favor of nothing in particular.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

With Trump's rise and the accompanying shift in conservative rhetoric from taxes and constitutional originalism to immigration, trade, and abstract ideas about "the nation," it can be difficult to remember that there was a time when none of these issues played a large role in Republican primary campaigns. The 2012 GOP primary was a year-plus-long contest of right-wing one-upmanship about other things.

These were the days of Herman Cain and the infamous 9-9-9 plan. The latter sounds like a pizza marketing gimmick — befitting Cain's status as the former CEO of the Atlanta-based Godfather's pie chain — but at the time it was a deadly serious and widely popular proposal for eliminating all federal taxes — including payroll, capital gains, and estate taxes — and replacing them with a 9 percent rate that would be applied to income, sales, and businesses respectively. Newt Gingrich promised that "by the end of my second term, America will have the first permanent base on the moon." Everyone remembers Rick Perry's infamous "oops" moment in November 2011, when he failed to remember the name of one of the three supposedly worthless federal departments he planned to eliminate entirely. What everyone forgets is that abolishing entire government agencies with the stroke of a pen was a perfectly ordinary thing for a GOP candidate to propose back then. This was true even of the Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of Homeland Security, both of which were created by Republican presidents.

The gaffes in those days, too, were the stuff of legend. Cain used to recite words from the soundtrack to Pokémon: The Movie 2000 and insist that they were verses from an unnamed poet. Michele Bachmann was probably the most unintentionally funny candidate for president in American history. During the first and only Tea Party presidential election, when it was common to see people attend rallies in tricorn hats (I wonder what happened to all of those?), Bachmann told a crowd in New Hampshire that they should be proud to reside in the state in which the Shot Heard Round the World was fired. She also claimed that she liked reading the Austrian school economist Ludwig von Mises at the beach. (His books are full of sentences like this one: "The fact that man does not have the creative power to imagine categories at variance with the fundamental logical relations and with the principles of causality and teleology enjoins upon us what may be called methodological apriorism.")

We all know how this madness ended. Bachmann did not show up dressed as Betsy Ross and kill a terrorist on stage. Ron Paul, in his third and final bid for the presidency, did not ride into the convention in Tampa and announce the imminent disestablishment of the Federal Reserve or the return to the state appointment of senators. Rick Santorum did not, alas, establish an American version of 13th-century France. Newt didn't fly us to the moon. Instead, after the math became blindingly obvious on Super Tuesday, Mitt Romney, the heir apparent from 2008, won the nomination handily. He went on to run a very boring general election campaign and lost handily to an incumbent whose considerable weaknesses he was almost totally unable to exploit.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What are the lessons here for Democrats in 2020? The first is, of course, that intellectual purity contests are not interesting to anyone except journalists and a small but vocal minority even among primary voters. You can try to strong-arm the entire field into saying that crossing the border illegally should not be considered a crime and turn abolishing ICE or supporting single-payer health care into a litmus test. It probably won't make a difference when the general election rolls around. This is because whoever happens to be the nominee is going to spend most of his or her time pretending the whole thing never happened.

What about Romney's example here? Does this suggest that no matter what Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren or Kamala Harris do, Joe Biden is inevitable? I'm not sure. Biden has far more personal and ideological baggage than Romney ever did, and he has been careless in ways Romney rarely was before winning the nomination. But he is also more beloved by the Democratic base than Romney ever was among Tea Party grassroots types, who tended to find him smarmy and insincere for reasons that were perfectly obvious to ordinary American voters and absolutely invisible to the blinkered GOP consultant class. Biden might refuse to compete in a given week's episode of Who Wants to be a Woke Millionaire?, but that is arguably to his advantage. The people who complain most loudly about how the front-runner is wrong about issues x, y, and z are not necessarily the same people who actually show up on election day — in fact, they might be the most likely to stay home if they don't get their way.

If all this means for the 2020 presidential election is that someone like Marianne Williamson is going to propose a 100-100-100 percent tax plan before dropping out with a speech in which she attributes dialogue from The Land Before Time IV: Journey Through the Mists to William Blake, I for one am not going to complain.

Matthew Walther is a national correspondent at The Week. His work has also appeared in First Things, The Spectator of London, The Catholic Herald, National Review, and other publications. He is currently writing a biography of the Rev. Montague Summers. He is also a Robert Novak Journalism Fellow.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred