Just allow presidential indictments

Everything would be clearer if the president could be indicted

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

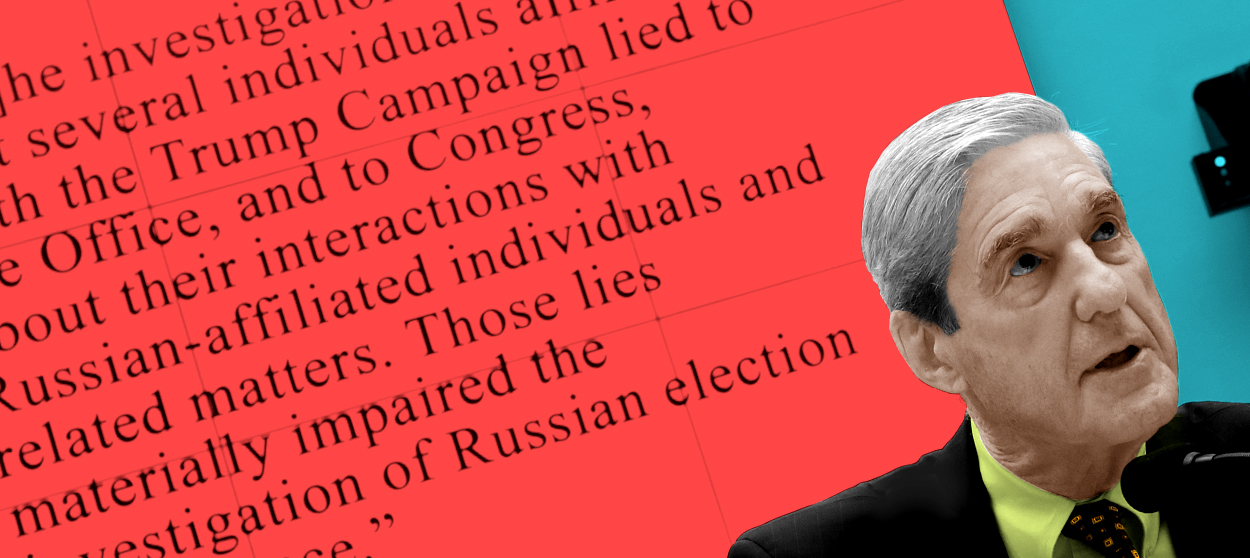

The easiest way to have sidestepped the markedly unproductive and repetitive congressional hearing with former Special Counsel Robert Mueller on Wednesday would have been for members of Congress to personally read his report in its entirety, a task which the naive among us might have expected them to complete anyway.

The best way, however, would have been to make it possible for sitting presidents to be indicted.

This is not as radical as it might sound. (Some legal experts believe it's perfectly possible already, but the Justice Department disagrees.) You don't have to go full French Revolution, ready to lop off the head of state, to make the occupant of the nation's highest office answerable to the nation's criminal code — or at least more easily subject to legal consequences.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Other countries do something like this already. In some European nations, the chancellor or prime minister enjoys special legal protections, but they are fewer and more easily overcome than those accorded to our president.

In France, for example, recent reforms expanded the causes for which the president may be impeached from "high treason" to any "breach of their duties that is clearly incompatible with the exercise of their mandate." In Germany, only a simple majority vote in parliament is required to remove immunity from the president or chancellor, the latter of whom may also lose office — and immunity with it — far more easily than our system allows. In Britain and Commonwealth countries like Australia and Canada, members of parliament, including the prime minister, do not have immunity from prosecution for crimes committed outside of office, and a parliamentary vote can void immunity for alleged crimes in office, too.

Particularly interesting in this regard is Israel, where the attorney general is presently preparing to indict Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu on corruption charges including bribery and breach of trust. Much like his counterpart here in the States, Netanyahu has responded to investigation of his behavior with vehement protest. No one else would be exposed to this "outrageous" and "unprecedented witch hunt," Bibi insists. Yet despite his objections, Netanyahu's prosecution appears likely to proceed to court, helmed by his own former Cabinet secretary.

When I say American presidents should likewise be subject to criminal prosecution, I am not coyly communicating a belief that President Trump should be prosecuted for a crime. I am saying it would be far easier for a fair observer to decide whether he should be prosecuted were prosecution now possible. (It would also be a positive step toward reining in the imperial presidency, whose current immunity has a real l'état, c'est moi vibe.)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The limiting effect of presidential immunity was a consistent feature of Mueller's testimony Wednesday. His team "at the outset determined that we — when it came to the president's culpability, we needed to go forward only after taking into account the [Department of Justice's Office of Legal Counsel (OLC)] opinion ... that a sitting president cannot be indicted," he told Rep. Jerry Nadler (D-N.Y.).

"Is it correct that if you had concluded that the president committed the crime of obstruction, you could not publicly state that in your report or here today?" Nadler later asked. "Well, I would say you could ... that you would not indict," Mueller replied, "and you would not indict because under the OLC opinion a sitting president ... cannot be indicted."

This labyrinthine language will only prolong the confusion and debate sparked by what may be the Mueller report's two most parsed sentences: "If we had confidence after a thorough investigation of the facts that the president clearly did not commit obstruction of justice, we would so state. Based on the facts and the applicable legal standards, however, we are unable to reach that judgment."

The "applicable legal standards," as Mueller reiterated Wednesday, include the OLC prohibition on indicting a sitting president. So the special counsel's team did not announce a conclusion on whether the president committed criminal obstruction of justice significantly because it could not indict him for the crime.

That non-answer is endlessly flexible and divisive: For the president's defenders, the important takeaway will always be that there was no indictment, so to continue harping on the subject is unfair sabotage of an innocent man. (Indeed, some, like Rep. Jim Sensenbrenner [R-Ill.] at the hearing, will argue that any investigation of the president is inherently unfair because the lack of indictment is a foregone conclusion.) For Trump's foes, the obvious implication is that the only reason Mueller didn't indict the president for incontrovertible crimes is because he wasn't allowed to.

Were it possible to indict a sitting president, this question in theory could be settled. We could dispense with all these hypotheticals and double negatives. We could finally get a straight answer from Mueller in the form of a presidential indictment — or none.

Bonnie Kristian was a deputy editor and acting editor-in-chief of TheWeek.com. She is a columnist at Christianity Today and author of Untrustworthy: The Knowledge Crisis Breaking Our Brains, Polluting Our Politics, and Corrupting Christian Community (forthcoming 2022) and A Flexible Faith: Rethinking What It Means to Follow Jesus Today (2018). Her writing has also appeared at Time Magazine, CNN, USA Today, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, and The American Conservative, among other outlets.

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy

-

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’Feature New insights into the Murdoch family’s turmoil and a renowned journalist’s time in pre-World War II Paris

-

Witkoff and Kushner tackle Ukraine, Iran in Geneva

Witkoff and Kushner tackle Ukraine, Iran in GenevaSpeed Read Steve Witkoff and Jared Kushner held negotiations aimed at securing a nuclear deal with Iran and an end to Russia’s war in Ukraine

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred