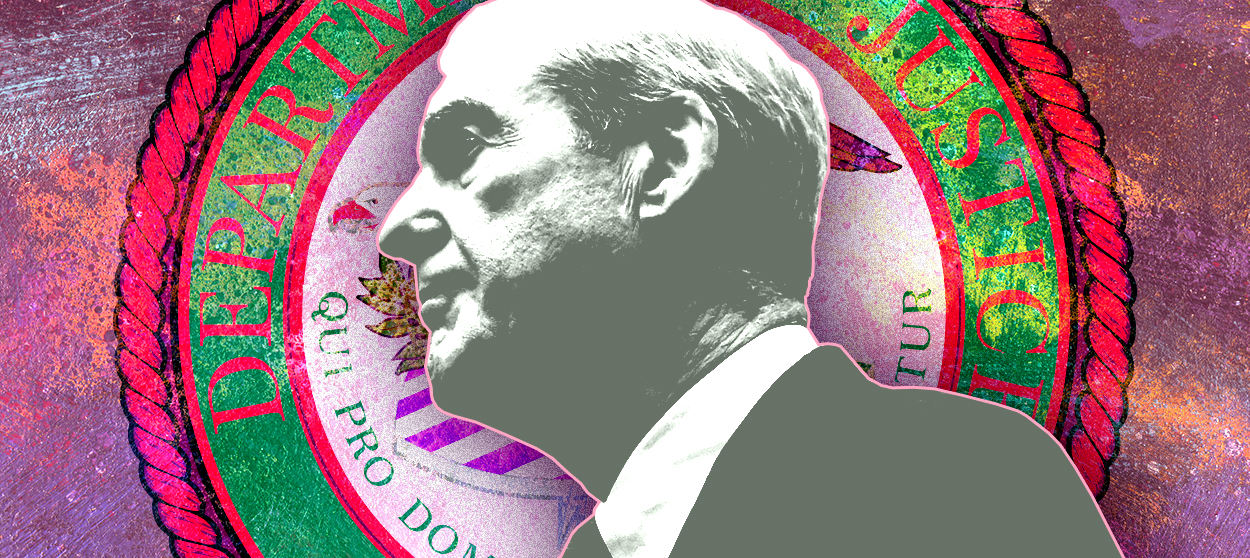

Robert Mueller, the improbable destroyer of the DOJ

The justice system has become an arm of the executive branch, and Mueller is partly to blame

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

For nearly two years, many decent people horrified by President Trump's conduct believed that Robert Mueller would somehow deliver the country from its awful predicament. Either his special counsel investigation would lead to indictments of Trump and his associates, or it would at least state without ambiguity that serious crimes were committed and that the president should be impeached. But it became depressingly clear early in Mueller's long-awaited congressional hearings that he will never do either of these things.

No doubt motivated by high-minded commitment to the principles of America's justice system, Mueller has nevertheless become complicit in its hostile takeover by forces bent on ensuring that Trump is never held accountable for his actions. And with his refusal to use sharper language to assess Trump's conduct, Mueller has effectively given his assent to that nefarious project.

This is not to say that Mueller's big day passed without drama. He confirmed there had been an active Russian campaign to undermine the 2016 election, and that the Trump campaign eagerly received and benefitted from this assistance. Several other moments from Mueller's testimony gave observers hope that Mueller was going to clarify his positions on important questions regarding the president's criminal culpability. One was an exchange with Rep. Ken Buck (R-Colo.). Buck asked, "Could you charge the president with a crime after he left office?" Mueller replied "Yes." Buck went on, "You believe that he committed — you could charge the president of the United States with obstruction of justice after he left office?" Mueller said yes again.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But even in this instance, Mueller was maddeningly unwilling to provide clarity. Was he talking about this president or just any president? To say that you could charge the president does not answer the question of whether Mueller would, or whether he believes that this is the proper course of action should Congress abstain from impeaching him and should Trump then lose his bid for re-election next year.

Mueller repeatedly confirmed that he believed existing policy from the Justice Department prevented him from charging a sitting president. Under questioning by Rep. Veronica Escobar (D-Texas), he refused to confirm that impeachment is the constitutional process he believes should be used to deal with criminal misconduct by a president. "I'm not going to comment on that," he said, when Escobar put this to him directly.

And on and on it went. Terse one-word responses that left potentially explosive allegations hanging in the air. "I can't get into that." "I'd refer you to coverage of this in the report." He dodged questions 206 times! I yearned not only for Mueller to deliver some kind of defense of his integrity and the reputations of his staff, but also for him to issue a clear verdict about what he thinks. What is holding him back at this point? He is a private citizen, presumably now retired for good, and he is no longer bound by DOJ rules except as they relate to "ongoing matters." Why not just come out and say what he thinks? He obviously believes that Trump committed a wide variety of crimes both prior to the election and during the subsequent investigation. He alluded to this in the report, and again yesterday. But he wouldn't say it directly.

Mueller does not want to get drawn into the partisan fray, and that's understandable. His reputation as a straight shooter was essential for reaching the pinnacle of his profession and earning the trust of luminaries in both parties. But it's hard to understand how you can devote nearly two years of your life to producing a report, the findings of which are critical to the future of American democracy, and not mount a more convincing and affirmative case for what you uncovered. He should have pushed back when Rep. John Ratfcliffe (R-Texas) claimed that Mueller lacked the authority to even write a report about matters that wouldn't result in an indictment. Instead of saying "outside my purview" when Republicans like Rep. Louie Gohmert (Texas) prattled on with their tiresome grandstanding about Fusion GPS and Peter Strzok or whatever they read on the Fox News crawl on their way into the office that morning, he could have turned the tables.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

More importantly, Mueller's continued trust in Congress to address the president's crimes is wildly misplaced. It's as if you were conducting a trial with two juries: one full of friends of the accused, and one full of enemies. And you need both to convict. Perhaps he thought remaining utterly opaque in his testimony would give Democrats the political cover they need to begin impeachment proceedings. But even if that were the case, there would have been great value in forthrightness.

The ideals to which Mueller is committed — the non-partisan nature of the Department of Justice and the FBI, and the importance of not salaciously impugning individuals who aren't being charged with crimes — are the very ideals his reticence most endangers. From the moment Attorney General William Barr's mendacious summary of the Mueller report was released to the public, it has been clear that Mueller does not see or appreciate the long-term damage that Trump, his minions, and their apologists are inflicting on American democracy and justice. By allowing Trump and Barr to openly and unapologetically resituate the DOJ as a political arm of the executive branch, Mueller has unwittingly turned himself into a vessel for their ambitions.

Perhaps this was always too much responsibility to place on one cautious man and his small team of public servants. But the president's strategy — to enlist his allies in the conservative media in a bid to turn the Republican base against the investigation's very legitimacy — has been clear from the day the probe was announced. Fox News talking heads, Republican elected officials, and op-ed writers quickly coalesced around an absurd narrative that the so-called Deep State had launched a plot during the 2016 presidential election to destroy Trump, and that the Mueller probe was that plot's apotheosis. That collective psychosis was on full display for all the world to see during Mueller's testimony every time an elected Republican spoke. And it worked.

After firing the FBI director and then admitting on national television that he had done so to shut down the Russia investigation, the president used his one-way Twitter bullhorn to relentlessly attack Mueller himself, the "17 Angry Democrats" (the number fluctuated) and anyone who cooperated with the "witch hunt hoax." He abused and threatened potential witnesses, like his former lawyer Michael Cohen, in public. He mused about pardons for those who kept their gums glued together. He ran his own attorney general, Jeff Sessions, out of town after assailing him endlessly for recusing himself from the probe, and replaced him with a compliant stooge whose lifelong dedication to the fortunes of the Republican Party supercedes any commitment to the rule of law.

Now, the presumed independence of the DOJ from the president is in ruins. If no one is willing to criticize or change the Office of Legal Counsel guidelines that say a sitting president cannot be indicted, and if Congress can't be trusted to do its job by removing corrupt executives from office, then we have essentially granted license to all future presidents to fire prosecutors, shut down investigations, turn special counsel investigations into punching bags and laughingstocks, and to brazenly engage in criminal conduct with utter impunity. Mueller, like so many old Beltway hands clinging to a long lost world, believes that at some point in the near future, his dream palace of bipartisan high-mindedness will magically bring itself back into being, thus retroactively vindicating his decision to hold himself aloof from the aftermath of the Russia probe.

It's not happening. And by failing to unambiguously spell out what he believes the president has done and the price that should be paid for it, he failed us all.

David Faris is a professor of political science at Roosevelt University and the author of "It's Time to Fight Dirty: How Democrats Can Build a Lasting Majority in American Politics." He's a frequent contributor to Newsweek and Slate, and his work has appeared in The Washington Post, The New Republic and The Nation, among others.

-

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’Feature An office doormat is stranded alone with her awful boss and a frazzled therapist turns amateur murder investigator

-

Movies to watch in February

Movies to watch in Februarythe week recommends Time travelers, multiverse hoppers and an Iraqi parable highlight this month’s offerings during the depths of winter

-

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance iceberg

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance icebergIN THE SPOTLIGHT Federal troops are increasingly turning to high-tech tracking tools that push the boundaries of personal privacy

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred