We're still not very good at predicting the weather. Politicizing it doesn't help.

Trump's tantrum over Hurricane Dorian would be funny if it weren't so dangerous

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The weather has always been political. From Bible stories that describe divine forecasts of flood and storms, to the correlation between rainfall and political assassinations in ancient Rome, the ability to anticipate and respond to weather-related phenomena has long been understood to make or break leaders. For modern examples, look no further than the fallout after Hurricane Katrina, or the urgent fight currently taking place over climate change.

But only very recently has the uncertainty of weather prediction also started to be exploited for political gain.

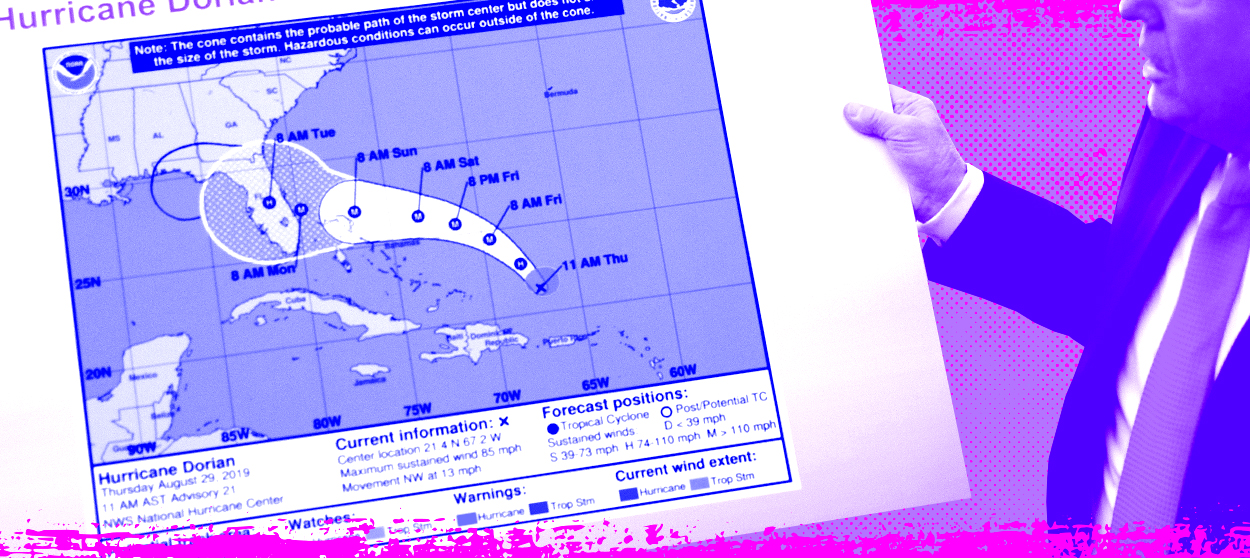

On Sept. 1, President Trump infamously claimed that Alabama "would most likely be hit (much) harder than anticipated" by Hurricane Dorian, a statement that was then refuted by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), then defended by the agency, and is now the subject of an internal investigation and a growing scandal involving Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross. While the whole snafu snowballed into a kind of theater that was almost comical — involving doctored maps and rage tweets — the underlying implication of the whole affair is much more worrying: That the inherent unknowableness of a forecast can be a political tool, too, and one that can carry deadly consequences if not taken seriously. "This is the first time I've felt pressure from above to not say what truly is the forecast," one anonymous employee at the national meteorological agency said.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Predicting the weather is something America is surprisingly not great at. Compared to European weather computer models, NOAA in particular tends to be more prone to error — most devastatingly, in the case of its estimation that Hurricane Sandy would weaken out over the ocean, while in reality over 200 people died after the storm strengthened as it turned back into New York. The agency is also plagued by bureaucratic deficiencies ranging from a 40-year-overdue software update to concerns that interference caused by a 5G wireless network could set NOAA back "several decades" in its ability to model weather patterns (not to mention the president's attempts to severely slash its budget). As a result, there can be a lot of wiggle-room around NOAA's estimations, if you suddenly find yourself, say, needing to support a gaffe you made: Hurricane Dorian might not actually be on track to hit Alabama, but hey, it could!

You're not supposed to look at weather models this way, though; let's not forget that the cone-shaped projection of a hurricane is literally called "the path of uncertainty" for a reason. (Alabama was never "likely" to be "hit much harder than anticipated," no matter how you read one stray NOAA model). Even the European weather models, while having a slightly better track record, aren't correct every time. This lack of certainty can be obnoxious as a layperson: Just this past winter in New York City, the National Weather Service (NWS) — an arm of NOAA — warned of an approaching storm so big it could have dropped 10 inches of snow in Central Park overnight. Due to a slight change in temperature and direction, the model was a dud; there was so little slush on the ground when New Yorkers woke up that the agency's goof became a meme, and the affair an embarrassment for city officials.

But as infuriating as it can be to have a snowless snow day, it is of the utmost importance that Americans put their trust in NOAA regardless of its occasional misfires. Meteorologists are still a lot more accurate than you think they are! Plus, between the internet's plethora of amateur meteorologists and the easy dissemination of illegal viral weather hoaxes, there is already far too much conflicting information in circulation. Adding to the noise, scammy, popular weather apps exploit the uncertainty surrounding weather forecasts, not even bothering to use real scientists to put together their predictions. Even though private weather agencies can have the reputation of being more accurate than a government agency, it is NOAA and the NWS that actually have the infrastructure in place to do the high-quality data collection required to predict potentially devastating storms (or, you know, if you ought to take an umbrella with you to work). Terrifyingly, Trump's attack and NOAA's subsequent flip-flopping have now further tarnished its reputation as a reliable source.

Meanwhile, people are dying. For all that Hurricane Dorian might seem an example of an Orwellian turn by NOAA — the agency relegated to a puppet of the president's misinformation campaign to protect himself — the storm is really best interpreted as yet another warning shot by our warming world. Hurricane seasons are only going to get worse as climate change progresses, NOAA itself predicts; the years ahead will hold more Dorians and Marias and Sandys (the Bahamas, which bore the brunt of Dorian's intensity, will likely be struggling to recover for months to come). It is vital that we continue to pour our resources into limiting the gray area around predictions while also preparing for the worst; it could be the difference, quite literally, for thousands of lives.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Yet for as long as weather remains a final frontier in science, the potential for gray area exploitations will persist. The floodgates have been opened by Trump's cherry-picking of NOAA models to back-up his gaffe; it isn't such a stretch to imagine NOAA similarly being weaponized by politicians to mitigate blame for poor preparation (it wasn't supposed to hit us!) or hinge badly-needed infrastructure and zoning decisions on the basis of an if.

The fact of the matter is, the weather isn't political: It doesn't vote, or care who's president, or have an agenda about which states it decimates. It's up to us to ultimately react to the facts: That southeastern Alabama never got more than nine-mile-per-hour winds last week; that the Bahamas are badly in need of our aid; that Puerto Rico is still recovering from the aftereffects of Maria two years later; that hurricanes are going to get worse until our models and policies reflect the facts of climate change. That, we can do something about. That, at least, is black and white.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Jeva Lange was the executive editor at TheWeek.com. She formerly served as The Week's deputy editor and culture critic. She is also a contributor to Screen Slate, and her writing has appeared in The New York Daily News, The Awl, Vice, and Gothamist, among other publications. Jeva lives in New York City. Follow her on Twitter.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred