A brief history of treason in the United States

Emphasis on brief

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

"What makes treason here?" asks Ferdinand in Love's Labour's Lost. Unless you have been living under a rock in Outer Mongolia, you might be asking yourself the same question. On Monday, President Trump accused his critics of treason. Many of them have responded in kind, including Bill Weld, an ostensible challenger to the Republican presidential nomination. Both men are participating in a rhetorical tradition that is as old as the American republic.

The history of actual treason, in the sense of federal criminal prosecutions for the concept defined in the Constitution and adopted almost immediately as a federal offense, is remarkably short. Since the ratification of the Constitution in 1789, there have been only 40 federal treason cases, and far fewer convictions. (John Adams secured the passage of the Alien and Sedition Acts in part because the constitutional definition of treason was too narrow.) Even the most famous "traitors" in American history were not technically guilty of treason. Benedict Arnold might plausibly have argued that it was those on the side he betrayed who were guilty of treason; Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were actually convicted of conspiracy to engage in espionage.

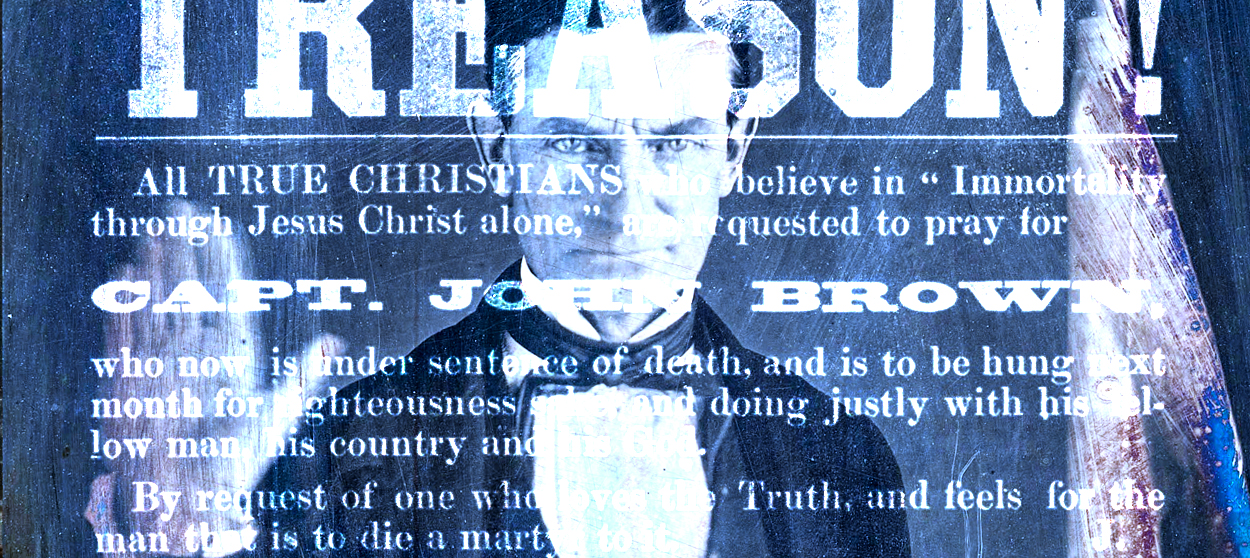

Otherwise the record is remarkably sparse. In 1794 Philip Vigol and John Mitchell were convicted of treason for their part in the Whiskey Rebellion and sentenced to death. Both were pardoned by President George Washington. Six years later, John Fries, the leader of the eponymous rebellion, was convicted of the same offense; he also received a pardon, from John Adams. Aaron Burr was rather famously acquitted in 1807. In April of 1862, William Bruce Mumford was found guilty of treason after removing an American flag planted by Union Marines atop a mint in New Orleans. Mumford was hanged. During this period, the states also occasionally secured convictions for treason. John Brown was executed in 1859 for crimes against the Commonwealth of Virginia, not the United States. Joseph Smith was charged with treason by the governments of both Missouri and Illinois; he was killed by a mob in 1844.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In the 20th century, not a single person was put to death for the crime defined as "War against [the United States], or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort." Walter Allen was convicted of treason in 1922 for his part in the Battle of Blair Mountain, the climax of the West Virginia coal wars. He was given a sentence of 10 years and fined, but would later disappear while out on bail pending an appeal before the Supreme Court. Two decades later several German Americans were convicted for assisting a German sabouteur; Martin James Monti, an Air Force pilot, defected to the S.S. in 1944 and was subsequently sentenced to 25 years before receiving parole in 1960. Tokyo Rose was convicted in 1949, as was Axis Sally; the former was pardoned by Gerald Ford, the latter served 12 years. Tomoya Kawakita was sentenced to death in 1952 for abusing American POWs in Japan during the war but would be deported by the Kennedy administration. The Nazi propagandists Herbert John Burgman and Robert Henry Best both died in the same Springfield, Missouri, prison. In 1990, the death penalty for treason was formally abolished. In 2015, Adam Yahiye Gadahn, the Oregon-born al Qaeda hype man, was killed by a drone in Pakistan.

This more or less exhausts the legal history of treason. Its rhetorical vein is much richer, and there is good reason to think it will never be exhausted. Washington and Alexander Hamilton repeatedly accused their critics of treason. Thomas Jefferson insisted in 1791 that anyone who had business with the newly established Bank of the United States was guilty of treason and should "be adjudged guilty of high treason and suffer death accordingly." This did not happen, and after 1803 such accusations became infrequent. After the Civil War there were frequent calls for the leaders of the Confederacy to be charged with treason, but the precedent established by Grant's blanket amnesty at Appomattox was honored at subsequent surrenders, and enshrined in law by Andrew Johnson in 1869.

The modern rhetorical history of treason really begins in the middle of the 20th century. It is here that we see a revival of treason as a kind of catch-all for one's partisan opponents, which is how it had been deployed in the struggles between Federalists and Republicans in the early history of the republic. In 1954, Joseph McCarthy accused the entire Democratic party of "20 years of treason." He was met with raucous applause by a crowd of 6,200 supporters. By the time that Ann Coulter (a future biographer of the Wisconsin senator) published her eponymous bestseller, Treason: Liberal Treachery from the Cold War to the War on Terrorism, in 2003, treason had already become the watchword of George W. Bush's opponents on the fringes of the left.

With the inauguration of Barack Obama all bets were off — or rather, they were all in, at any odds, on the action that he had committed treason. When Obama bowed to the emperor of Japan, it was treason. In 2014 Ted Cruz bungled Cicero in an attempt to accuse Obama of being "openly desirous to [sic] destroy the Constitution and this Republic," which is treason without the word. The same year, a GOP candidate in Florida called for Obama's execution for treason. Nor was Obama himself the only member of his administration with whom the word would become synonymous among Republicans. Hillary Clinton was repeatedly accused of treason both during and long after her tenure as secretary of state. One New Hampshire lawmaker (and sometime adviser to our current president) even suggested that she should be executed by firing squad. In 2011, George Duff, who maintained that Obama was guilty of treason against the United States despite not believing that the president was a citizen of this country, was convicted in a terrorist plot to seize a courthouse in Tennessee.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Republicans were not alone in this activity. By the end of the administration it had become common for the president's supporters to accuse GOP senators who disagreed with, for example, the administration's Iranian policy of brushing up against treason. There were even meta-debates about whether wishing for Obama's failure in fact constituted treason. (Around the same time there was also a great deal of talk among liberals about the necessity of making the impeachment process much more difficult.) By the end of Obama's second term even Republican senators' refusal to push forward Merrick Garland's nomination to the Supreme Court was "tantamount to treason."

But all of this pales in comparison with the Trump era, during which I doubt a single week has gone by without a discussion of treason either by or from Trump and his supporters appearing in a major media outlet. In the halcyon days of June 2016, it was still possible for The Washington Post to ask in a headline "Is Donald Trump suggesting that Barack Obama committed treason?" I think it is fair to assume that the columnist's query has since been answered — "answered" in the double sense that it is both clear beyond any doubt that Trump has indeed accused Obama, Clinton, and numerous other opponents of treason and obvious that his own critics are just as willing to level the same charge against him for virtually everything, including making jokes during press conferences.

This has continued well after Trump's inauguration and kept pace ever since. By 2017 some observers were detecting a whiff of treason in Washington; for others the "smell of treason in the air" was general, diffuse, all-pervading. It was asked whether there is a proper emoji for treason. It was even suggested by a flag-throwing protestor that in some kind of bizarre ontological sense that "Trump is treason." A non-exhaustive list of persons other than Trump himself who accused of treason before, during, or after the special counsel's Russia investigation includes Michael Flynn, Donald Trump, Jr. (including by his father's former vice-presidential rival Tim Kaine among others), and Jared Kushner.

What explains the popularity of this unusually precise legal term as a partisan epithet? The fact that it places one's enemies outside the bounds of whatever is supposed to constitute normal American political discourse. The terms of the conflict change. The quarrel is no longer a prudential disagreement about the best means of securing the common good, but a noble struggle to extirpate an alien element from the body politic. A traitor cannot argue for or explain away his actions; he can have no recourse to questions about his motivations. It is not difficult to see why the tool would be wielded frequently and enthusiastically by both of our major political parties.

A more important question is whether these accusations of treason are dangerous. In one sense the answer, I think, is obviously no. Any word whose currency has been so thoroughly debased is all but meaningless. It might be argued that a would-be contest of ideas — you know, the whole democracy thing — between two factions who each insist that the other has forfeited its right to take part at all is not one that is likely to inspire confidence or good faith, much less safeguard the common good. But this, I think, would mean confusing a symptom for a cause.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Matthew Walther is a national correspondent at The Week. His work has also appeared in First Things, The Spectator of London, The Catholic Herald, National Review, and other publications. He is currently writing a biography of the Rev. Montague Summers. He is also a Robert Novak Journalism Fellow.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred