Why Bolivia doesn't fit the pattern of historic Latin American coups

This wasn't your classic U.S.-funded golpe de estado

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

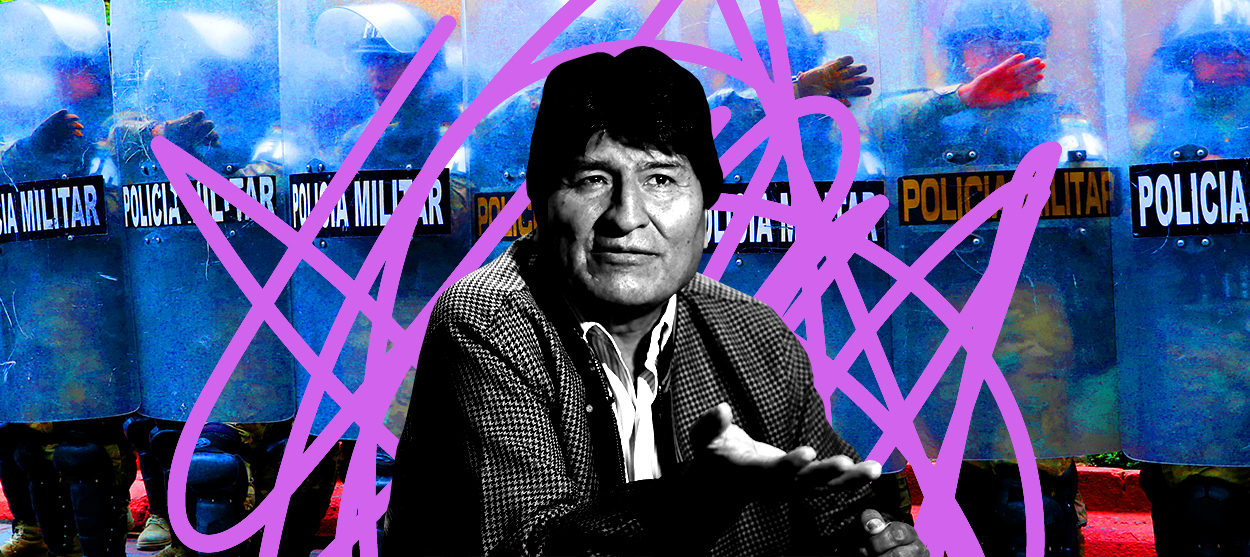

On November 10, Bolivian president Evo Morales — who was elected by 61 percent of the population in 2014 — was removed from power via a coup d'etat.

In the days since, progressive politicians around the world — including U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders and Reps. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Ilhan Omar — have expressed their concern, comparing the situation to past U.S.-backed military takeovers in Latin America.

But I believe it's inaccurate and irresponsible to compare what is unfolding in Bolivia with historic coups like General Augusto Pinochet's takeover of Chile in 1973. Rather, the person who brought Bolivia to the brink of insurrection was president Evo Morales himself, whose desire to hang on to power defied the popular will of the Bolivian people.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Protesters in Bolivia have described Morales' affliction with power as a "borrachera de poder" or a "power binge".

And in fact, power affects our mind in a way that is quite similar to other addictive substances. For example, when one introduces cocaine into their system the human mind experiences euphoria as dopamine and serotonin rush into neurotransmitters and stimulate the brain. After repeated use, when the effect of the drug wears off, the body goes through withdrawals as it searches for a new high. Something similar happens when we are allowed to hold power for long periods of time. Like cocaine, power blasts the mind with strong doses of dopamine and serotonin, and absent meaningful checks and balances, those who wield power begin to find themselves longing for more.

The rise and fall of Evo Morales is a perfect case in point.

Morales was born in 1956 to an Aymara farming family in the tiny town of Isallawi, which is south of Oruro. He served in the military as a young man and led the life of a poor coca farmer until his union leadership began to distinguish him in the late 1970s. In 1997 he rose to national prominence after he was elected to Congress. His socialist platform combined with his humble beginnings and strong advocacy for indigenous communities eventually made him an ideal candidate for president.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In 2006, under the Movement for Socialism (MAS) party, Evo Morales became the nation's first indigenous president. In a nation in which more than 60 percent of citizens are indigenous, his mere presence in the country's highest office spoke volumes about the potential for progressive change that he brought to the table. And across nearly 13 years in office, Morales and his administration delivered.

Since 2006, poverty rates have been cut in half, inequality has been reduced, and the nation's vast majority — the indigenous — have finally gained a voice in politics. Following his first victory at the polls, Morales pronounced, "a new history of Bolivia begins, a history where we search for equality, justice and peace with social justice." Not surprisingly, in a nation marred by colonial exploitation, Morales gained a messiah-like following.

But not everything Morales touched turned to gold. Mr. Morales ran on an eco-friendly platform in 2006 and promised to protect Mother Earth, known locally as "La Pachamama." Unfortunately, the progress he brought to Bolivia often came at the cost of the natural environment. Still, in a world where capital exploitation is nearly a precondition of progress, it wasn't his environmental policy flaws that led to his ultimate demise. Instead, it was something much closer to home.

Evo Morales refused to let go of his hold on power.

In 2006 Morales won his first election with a commanding 53.7 percent of the electorate. In 2011 he won again with 64.2 percent of the vote. At the time, the Bolivian constitution only allowed for two consecutive terms. However, Evo ran a third time in 2014 under the premise that he'd only run once under the new constitution, which was inked into law in 2006 during his first term.

Morales won his third election with a decisive 61 percent of the vote. Most assumed it would be his last term, but in February 2016, Morales put forth a referendum asking the people to abolish the constitution's term limits. For the first time in a decade, Evo lost. It was clear the Bolivian people were ready for power to change hands.

One year later, the Supreme Court argued that it would be a violation of Morales' human rights to restrict his ability to run as many times as he liked. So, in 2019 Mr. Morales ran for an unprecedented fourth term and on October 20, 2019, with just 47.1 percent of the vote — short of a majority and nearly 16 percent less than he won in 2014 — he declared himself the victor in the first round.

That's when people took to the streets and that is when Evo Morales — Bolivia's indigenous messiah — fell from grace.

So was there a coup d'etat in Bolivia?

Yes.

A coup d'état is the sudden seizure of power by the military, a dictator, or another political faction. And that's exactly what happened in Bolivia. The military forced Evo Morales to resign before his third term as president had ended. And although a popular insurrection was in the works, the ultra-right piggy backed on the movement unfolding in the streets and sped things up by working with the armed forces. In his wake, Jeanine Áñez has assumed power as interim president. She has promised to call new elections soon, but her racist and anti-idigenous rhetoric is evidence that Morales' departure may prove to be a big step backward for Bolivia and its people.

However, this wasn't your classic U.S.-funded golpe de estado. Rather, the coup against Evo Morales was the result of his refusal to alternate power. And in a world that is quickly drifting away from democracy, Morales' fall serves as an important reminder that all leaders, regardless of political ideology, are susceptible to the pernicious effects of power.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Benjamin Waddell is an associate professor of sociology at Fort Lewis College in Durango, Colorado. He is a father, husband, writer, professor, and advocate for social justice. He is a contributing writer for HuffPost, The Conversation, and Global Americans. He also has recent publications in Sociology of Development, Latin American Research Review, The Social Science Journal, and Rural Sociology.

-

Political cartoons for February 7

Political cartoons for February 7Cartoons Saturday’s political cartoons include an earthquake warning, Washington Post Mortem, and more

-

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'Cartoons Artists take on a girlboss, a fetching newspaper, and more

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred