A glimmer of hope for bipartisan economic sanity

Why Mitt Romney's child tax credit deal could signal a new mindset for Republicans

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

One thing Donald Trump's ascendency supposedly demonstrated was that lots of Republican voters don't actually care about cutting the welfare state or reducing government spending. Trump's campaign promised to boost jobs and protect big government entitlements, with deficit concerns more or less tossed to the wayside.

It hasn't worked out quite like that; Trump has simultaneously refused to cut programs like Social Security and Medicare that disproportionately benefit his base (older white people) while rabidly working to cut those that disproportionately benefit other demographics. But that doesn't mean the lesson about the electorate isn't true.

Enter one Mitt Romney, current GOP Senator from Utah, and a former contender for the presidency in 2012. Over the weekend, Romney teamed up with Michael Bennet, a Democratic senator from Colorado, to offer a remarkably sane reform and expansion of the child tax credit (CTC). It's a good idea on the merits, and the hope is it might help get the current Congress to a comprehensive budget deal before their end-of-year deadline. Even more encouragingly, it's a sign that maybe, once Trump's gone, less reactionary Republicans will find they have a window to propose sensible and humane economic policies that diverge from past party orthodoxy.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

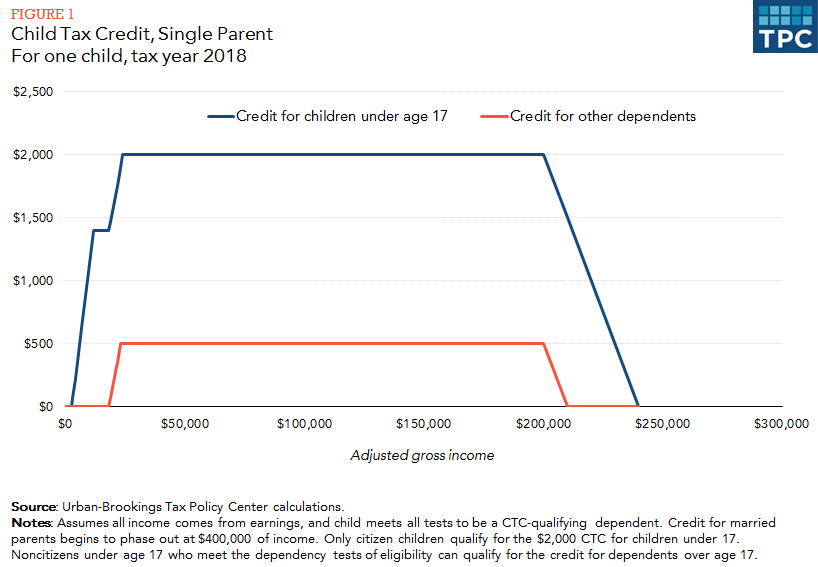

Currently, the CTC provides every family $2,000 per child under the age of 17 — which is to say, when you pay your taxes, the government cancels $2,000 of the taxes you owe. (Hence the "tax credit" part.) The complication is, the CTC isn't a flat $2,000 for everyone. The size of the credit actually phases in based on families' income, rising to eventually plateau at $2,000 as families' taxable income increases. Then it phases out again for families making over $200,000.

The result is the CTC's benefits are distributed in a kind of "trapezoid" shape along the income spectrum, which you can see in blue below. (The red line is a second bonus credit created by the 2017 Republican tax law, which also expanded the CTC.)

The other key thing to grasp is that the CTC is refundable, meaning that if the value of the CTC a family qualifies for exceeds the total taxes they owe, they get the remaining CTC money back as a check. It's essentially income support built into the tax code, which gives an extra boost to families of lesser means.

Unfortunately, the CTC's refundability is only partial: it also phases in with income, and is capped at $1,400. (Hence the little dogleg in the blue trapezoid above.)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

These phase-ins are meant to encourage work; the more money a family makes, the more CTC they get, up to a point. But the practical results are perverse: Thanks to the trapezoid shape, the poorest American families get much less help from the CTC than more relatively well-off households. In fact, some families don't get any help at all. According to the Tax Policy Center, of all the households in the bottom fifth of the income distribution, fully one-fourth don't see any CTC benefit, period.

What do Romney and Bennet propose to do about this?

First, they want to eliminate the $1,400 cap on refundability, and make the first $1,000 of the CTC fully refundable to all households. In other words, every American family, even if they have no taxable income at all, will get at least $1,000 back from the CTC. The next $1,000 of the CTC will still phase in with income, and still flatten out at $2,000.

Romney and Bennet also want to create an additional credit for children age six and under, which will max out at $2,500. The first $1,500 will be fully refundable, with the remaining $1,000 phasing in again.

Compared to the status quo, in which some of the poorest American families get little or no help from the CTC, the Romney-Bennet CTC would give all of those families at least $1,000 per child — and $2,500 if their child is six or younger. Policy analyst Sammuel Hammond, who's done a lot of work on this topic, whipped up a graph of what the new benefit distribution of the Romney-Bennet CTC would look like:

Granted, this isn't the best possible reform. Ideally, you wouldn't have any phase-in at all, and every family would get the full benefit of the credit even if they have zero taxable income. In fact, in an ideal world, you wouldn't use tax credits at all, as they still require Americans to go through the rigmarole of filing their taxes. Instead, we ought to just give households the money as a no-strings-attached check; a universal allowance rather than a tax credit. Finally, the benefit should be even more generous — a $3,400 annual child allowance, for example, would reduce child poverty by half.

Nevertheless, the Romney-Bennet CTC would be a big step in the right direction. Can it actually happen?

Maybe. Republicans and Democrats are haggling over a new package of tax reforms — both to provide Americans with some extra help, and to clean up some technical problems left behind by the 2017 tax changes — and Romney and Bennet may have just provided a centerpiece compromise to structure the rest of the bill around.

To get there, the proposal would still have to overcome obstacles on both sides. A CTC expansion would seem right up Democrats' alley, but a fair number of them may be hesitant to make a deal of any kind with Republicans right now. Meanwhile, the expansion also runs into all sorts of pre-existing conservative ideological hangups.

A lot of people on the right don't like refundability at all, viewing it as welfare rather than a tax break. Previous intra-GOP debates over the CTC have also been infected by classism — i.e. wealthy families deserve help with raising their children, but giving benefits to poorer families would just encourage "irresponsible" childbearing. Finally, there's the perennial worry that more generous child benefits will discourage work — though evidence from other countries suggests not.

But perhaps the most striking aspect of the Romney-Bennet proposal is the "Romney" part. The senator from Utah ran as a straight-forward austerian in 2012, when he tried to oust President Obama from the White House, running on promises to push through massive reductions in public spending and the welfare state. That Romney now feels comfortable signing his name to this idea suggests how much the ground has shifted — and how even centrist and establishmentarian Republicans may operate differently in a post-Trump world.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.