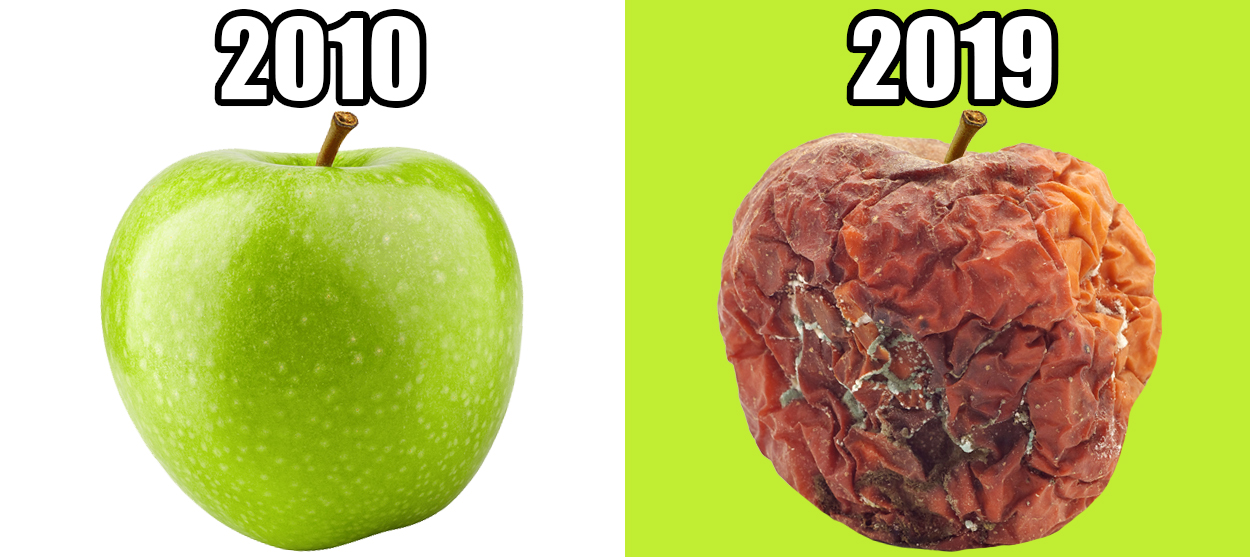

Humanity's decade of disillusionment and decline

The 2010s were an age of ever-increasing frustration and ever-diminishing expectations

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Looking back on a historical period from its end is a dicey proposition. Even when it is clear that a turning point has been reached, it is often hard to know with any certainty which way things are about to turn. At the end of the 1960s, how many confidently predicted that the moon landing would mark the high point of America's manned space program? Or, at the end of the 1970s, how many foresaw that the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan would prove the last gasp of a dying empire?

So it is with some trepidation that I look back over the course of the 2010s and try to sum them up. Unfortunately, the first draft of recent history doesn't make for pleasant reading. It's not hard to make a case for the passing era as the Downer Decade, an age of ever-increasing frustration, and ever-diminishing expectations.

The end of the 2000s, in spite of the fiasco of the Iraq War and the disaster of the financial crisis, was a relatively hopeful period in America, particularly in terms of the prospects for functional governance. America's first black president had been granted the strongest governing mandate since Lyndon Johnson: a decisive popular and electoral vote majority combined with control of the House and filibuster-proof control of the Senate.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But that moment was evanescent in the extreme. The 2010s began with a ferocious Tea-Party-led reaction that cost Democrats not only control of the House but of a host of governorships and state legislatures. Those losses ushered in six years of gridlock and escalating brinkmanship. The decade ends with the third impeachment in American history, of the relentlessly polarizing President Trump, playing out in an even more obviously partisan fashion than the impeachment of President Clinton. It is difficult for Americans to even imagine government from a widely popular center anymore.

Disillusionment in fundamental political institutions has not been confined to the United States. In Europe, the 2000s began with the advent of the Euro — adopted in 1999 and implemented as a replacement for national currencies in 2002. It ended with implementation of the Treaty of Lisbon in 2009, which deepened the union, beginning its transition to something more like a unified continental government.

That turned out to be the last moment of optimism about the European project. Instead, the 2010s saw the rise of insurgent reaction across the continent, with right-wing populist and nationalist parties dramatically gaining strength in France and Germany, sharing power in Italy and taking control of the government in Hungary and Poland. The decade came to a close with the landslide election of Boris Johnson's Conservative party in Britain on a platform of swiftly withdrawing from the European Union. It is no exaggeration to say that the project of European unity looks shakier than it has since its inception, without out any clear map for how it might be unwound or what might replace it.

What drove this unraveling of consensus across the West? Three shocks that reverberated across the decade were principally responsible, and though their roots lay before 2010, their impact was felt most profoundly in the decade just concluded.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

First, the full integration of China into the global trade system put manufacturing enterprises under sudden and profound stress from new competition, accelerating a decline in employment already underway due to the combination of globalization and automation. Second, the financial crisis caused a sharp economic contraction that was exacerbated in the U.S. by a finance-friendly approach to foreclosures in the underwater housing market and in Europe by a turn to fiscal austerity that saw debtor countries' tax bases collapse and unemployment soar. Finally, the dramatic rise in the size of immigrant populations from places as different as Eastern Europe, Central America, and North Africa interacted with these economic dislocations to transform politics across the West, with the right taking a turn towards nativism and the left adopting a more self-consciously transnational and multicultural ethic.

The consequences of dislocation have been felt well beyond either politics or economics. In the 2010s, America's total fertility rate plummeted to its lowest level in history, as marriage and childbearing increasingly came to be aspirational goods rather than a baseline expectation for most people. The opioid crisis began in the previous decade with overprescription of addictive painkillers, but it reached a new peak of lethality in the 2010s as first heroin and then fentanyl ravaged the country. America's suicide rate rose and average life expectancy declined.

Disappointment and disillusion have been fueled by developments not obviously related to these economic, demographic, and political dislocations. Consider our changing relationship to technology. At the end of the 2000s, optimism about the transformative power of information technology remained high. The internet had put a wealth of information at everyone's fingertips, while ubiquitous cell phones had enabled poor countries to leapfrog a whole generation of of development, and even empowered new political movements.

The 2010s were the decade when this technology turned on us. Social media turned the green fields of the internet into a series of personal gardens walled in by our own preferences and prejudices, and increasingly choked with weeds. Smart phones are increasingly implicated in widespread social ills, from a dramatic rise in teen suicide to a similarly striking decline in sexual engament. And far from liberating oppressed people, information technology has given an increasingly repressive China incredibly powerful tools for fine-grained social control. There are still techno-optimists out there, but it's striking that the most Silicon Valley-oriented candidate of the 2020 Presidential race is running largely because he believes automation is going to destroy modern society.

If the domestic trend lines look depressing, don't look abroad for solace. The 2010s saw a major retreat for democracy worldwide, and a global rise in populist, authoritarian and nationalist politics, from Russia to Turkey to India to Brazil. They also saw the unraveling of America's two major foreign policy efforts of the post-Cold War era, in the Middle East and in East Asia, with ominous consequences for decades to come.

Obama was elected in part because of his opposition to the Iraq War, and promised to turn America's relations with the Islamic world in a more positive direction. The Arab Spring, which began in 2010, raised hopes for a democratic transformation prompted not by American arms but by ordinary citizens armed with cell phones. Meanwhile, the killing of Osama bin Laden in 2011 raised the prospect of winding down the War on Terror.

By the end of the decade, any such hopes had withered entirely. America's intervention in Libya left that country in a state of chaos, and contributed to the destabilization of other countries like Mali. Egypt had reverted to a pro-American dictatorship while Syria's pro-Russian dictator won his own brutal battle to retain power. Under Trump, the U.S. tightened its embrace of the reactionary Saudi regime, assisting it in a near-genocidal war against Yemen, and ripped up Obama's one major diplomatic achievement in the region, the nuclear deal with Iran. Most depressingly, overwhelming evidence emerged that the military and civilian leadership believed we were losing our nearly 20-year war in Afghanistan for nearly the entire length of the conflict, but pretended otherwise. America had long since lost sight of any strategic or moral goals, yet the Forever War ground on.

Looking forward, though, it is the change in China that will likely prove to have the most lasting consequences. At the beginning of the 2010s, China had just capped 30 years of astonishing growth, emerging as a great power and potential rival to the United States. During the Great Recession, it invested heavily in its domestic economy, and appeared to have weathered the economic storm far better than America or Europe. The first Pacific president's "pivot" to Asia was largely about trying to manage China's rise in a way least-threatening to America's interests and those of our allies, but that very objective was an implicit compliment. Increasingly powerful and admired, Beijing could reasonably brag that the Chinese Century had arrived.

From the vantage point of 2019, the ambition to manage China's rise seems Pollyannish, as does the notion that economic engagement would lead to political liberalization and peaceful coexistence. Under Xi Jinping, China has become a far more threatening adversary, and more openly determined to revise the American-led geopolitical and economic order. The "belt and road" initiative aims to entrench Chinese economic and political influence across Asia and beyond, while China's social credit system has pioneered the use of modern technology for fine-grained social control. Oppression of minority groups like the Uighurs of Xinjiang has escalated dramatically, while Xi's total dominance of Chinese politics arguably has devolved the country into an autocracy. Meanwhile, China's slowing growth — in part a consequence of the very strategies that powered growth in the 2010s — prompt Beijing to be even more truculent in dealing with challenges, whether internal or external. Notwithstanding the supposed trade deal recently announced to much fanfare, the trajectory of Sino-American relations is toward economic disengagement and confrontation, a trend unlikely to be reversible no matter who wins the presidency in 2020.

That's a big problem for what is surely the worst trend line of the 2010s: the lackluster response to the looming threat of climate change. It should be no surprise that the decade was the warmest since scientists have been able to make proper measurements. What is more notable is that emissions continue to rise, driven primarily by increased fossil fuel use in China, as well as India and the rest of the developing world. But even climate leaders like Germany have stalled in their efforts to decarbonize their economies, while the United States has abdicated leadership entirely under the Trump administration. It will take extraordinary skill to advance the prospects for global decarbonization in the context of the reemergence of great power rivalry.

Meanwhile, the global failure to respond expeditiously to the climate crisis over the past decade means that no matter how aggressively we respond now, we are likely to overshoot the targets needed to stabilize the climate by mid-century. Sustainability may well depend on development and deployment of carbon removal technologies on a mass scale, alongside a program of decarbonization.

I'm tempted to end with a bitter and ironic "happy New Year" at this point — but I am mindful of the cautions of the first paragraph of this piece. At the end of 1939, with Poland divided between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union and Imperial Japan in control of large swathes of China, predicting the annihilation of the Axis powers and the formation of the United Nations in less than six years would have seemed extraordinarily optimistic.

So we should be wary of assuming that we know how the next decade will play out. Perhaps China will be bankrupted by its own expansionary spending, ecological devastation and demographic contraction, and 10 years from now we'll be reading about the Chinese century that wasn't. Perhaps the right-wing populist wave in the West will be supplanted by an era of decentralizing liberals who break up the big banks and tech companies, dismantle the European Union, and devolve much Federal authority to the states so that a breakthrough treaty between California and Germany can finally turn the climate tide.

It's impossible to say. But it is possible to say that we are unlikely to understand the dynamics of the new decade if we do not first see clearly how we got to the all-too depressing pass we're at. If ever an era both called for and promised a new clarity of vision, surely it is the one beginning with the year 2020.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Noah Millman is a screenwriter and filmmaker, a political columnist and a critic. From 2012 through 2017 he was a senior editor and featured blogger at The American Conservative. His work has also appeared in The New York Times Book Review, Politico, USA Today, The New Republic, The Weekly Standard, Foreign Policy, Modern Age, First Things, and the Jewish Review of Books, among other publications. Noah lives in Brooklyn with his wife and son.