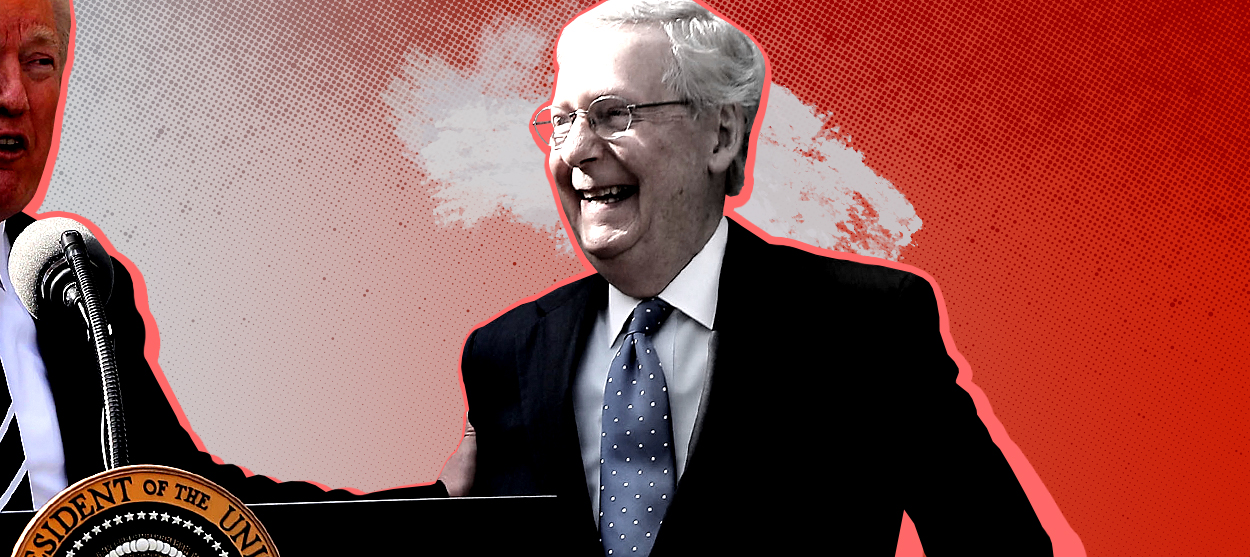

Mitch McConnell should recuse himself

Senate jurors are expected to be impartial. The majority leader is anything but.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

This afternoon, if all goes according to schedule, all 100 members of the United States Senate will take an oath to "do impartial justice" as jurors in the impeachment trial of President Trump. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) will be among those sworn in to judge the president's case.

If he takes the oath seriously, McConnell's first act after that should be to recuse himself.

McConnell won't do that, of course — he is the honey badger of American politics. But there can be no question that McConnell has no intention of approaching Trump's impeachment with impartiality. He has already passed judgment on the House of Representatives' case against the president — calling the Articles of Impeachment "weak" — and, more troubling, promised "total coordination" with the White House in steering the Senate trial to its conclusion.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"This is a political process. There is not anything judicial about it," he said in December. "Impeachment is a political decision."

Rep. Val Demings (D-Fla.) called for McConnell's recusal in December. She will serve at the trial as one of the House-appointed impeachment managers, and on Wednesday said she still believes McConnell should step aside.

"For the Senate Majority Leader to publicly announce that he has no intentions of being impartial and, as a matter of fact, he's coordinating every step with the White House and there will be no difference between the White House and his views, is absolutely shameful," she said in a press conference. "It's hard to take that one back and put that toothpaste back in the tube."

Demings is right.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

McConnell is too, sort of. It is true that the Senate is a political body. Most of its members have dreamed about being president; all of them have risen to their current positions — and stayed there — by being obsessively attuned to donors, voters, and anybody else with influence over their careers. Asking the most political people in the world to put politics aside and be impartial is nearly impossible. Even the Founders saw that.

And yet there's that darned oath.

The impeachment oath doesn't allow for exceptions. It doesn't obligate its takers to "do impartial justice" unless senators really like the president, or unless the political incentives make it difficult. It simply commands impartiality.

The three years of Trump's presidency have featured a lot of public pondering about why Republicans go along with his worst behavior, why — with rare exception — leaders like McConnell can't call him out, oppose him, or otherwise "put country over party." There are a lot of answers. Some of them involve their fear of Trump and his ability to end their political careers. Some of it is that they see what Trump has given them — tax cuts, deregulation, and a slew of conservative judges — and have decided this president's downsides are worth the benefits. And many Republicans don't put country over party because they truly believe that what is good for one is also good for the other.

That should be no surprise. Test a few Democrats, and you'd probably find they possess a similar belief.

Impeachment is different, though. The oath challenges senators to think hard and critically about the difference between what is good for the party and what is good for the country. It suggests that there is a higher duty than winning the next election, something more important than pledging allegiance to one's own biases. It requires politicians to do something they almost never have to do: be unselfish. Impartiality may be a nearly impossible standard, but there is something to be said for trying to live up to it.

McConnell probably won't make that attempt. He will take the oath and then immediately violate it — even if, as law professor Lawrence Lessig has suggested, that violation makes him a perjurer. Who, after all, will hold him accountable?

The impeachment trial is meant to judge Trump. But the ramifications go beyond this presidency. History is already starting to render its verdict on the honor of McConnell — the impeachment trial is one more piece of evidence that will find him wanting.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Joel Mathis is a writer with 30 years of newspaper and online journalism experience. His work also regularly appears in National Geographic and The Kansas City Star. His awards include best online commentary at the Online News Association and (twice) at the City and Regional Magazine Association.