Democracy didn't lose in Iowa. CNN did.

Speed is paramount to the chattering class, not to the functioning of a healthy democracy

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

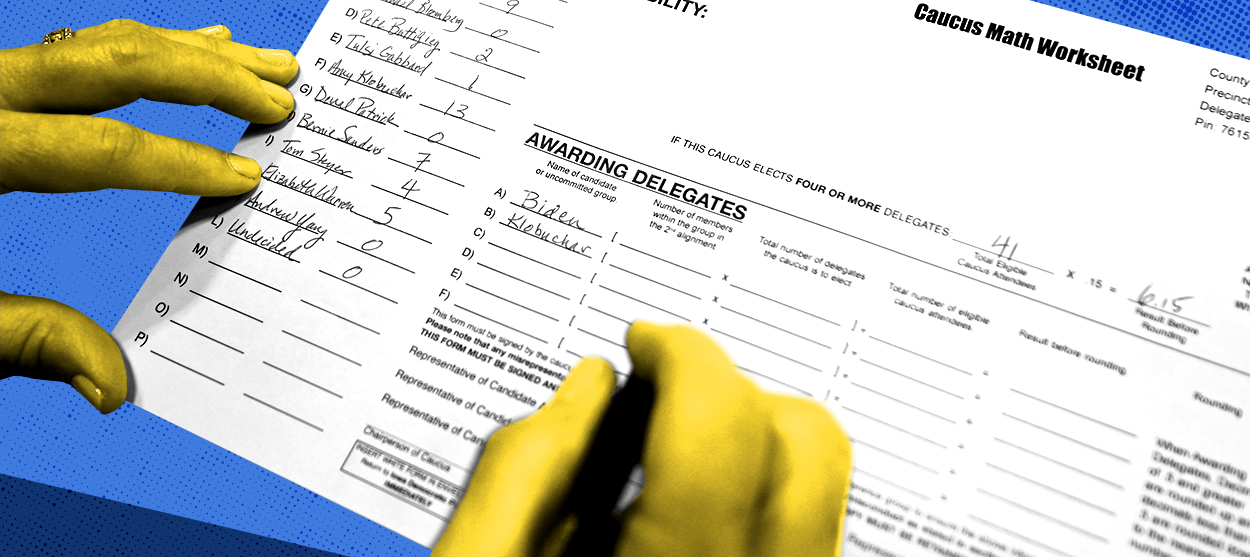

Let's begin by stipulating that though the Democratic Party of Iowa is likely not an organization composed entirely of witless incompetents or corrupt backroom dealers, it has managed to make an excruciating mess of what should have been a straightforward, if archaic and tedious, caucus event. In doing so, it has opened a wide door to conspiracy theories, further loss of institutional trust, and compelling argument against the very expansions of state authority the Democratic Party seeks.

Yet without excusing Monday night's very preventable chaos, the delay of the Iowa Democratic caucus results is no real loss to democracy proper. All that was really lost in this debacle was speed.

The caucuses, for all their flaws, have public votes. That means, in time (namely, as of this writing, Tuesday afternoon), accurate results will be duly counted and announced — maybe not with the expected fanfare, but still well before most primaries. This reality won't ward off the conspiracy theories (one can too easily imagine a defeated President Trump whining that his loss is illegitimate because he had to run against the wrong candidate due to the "cheating" in Iowa), but Iowa's caucus-goers have not actually been disenfranchised by the delay.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Cable news cannot be offered the same sanguinity: The people for whom the loss of speed matters are TV's talking heads. The moment of the caucus night media narrative is gone, lost forever. All those wild graphics packages teed up — for nothing. Hours of airtime to fill and no numbers to fill it. Is it any surprise cable hosts spent Monday evening ginning up frankly excessive outrage over this delay? For caucus-goers, accuracy is more important than speed, but for TV news, speed is the greater value: You get something to report immediately, and if it turns out to be wrong, that's a story, too.

Iowa has done us a favor by revealing, in its disarray, that mismatch of interests. And as willingness to rethink the structure and methods of our elections rises — see all the "no more caucuses" takes Tuesday morning, or bigger proposals like my call for ranked choice voting and party-list proportional representation in the House — we should use this opportunity to consider what we value most in our primary process.

Schemes for overhauling American primaries generally focus on one of three themes: speed, accuracy, or equity. The latter two receive the most attention. Accuracy is the value that motivates demands for paper ballots as tangible, verifiable evidence of voters' intent which isn't at risk of digital manipulation, not least by foreign hackers. Equity is behind suggestions of a single day of primaries which would no longer allow a handful of states to disproportionately shape the race, pre-emptively sinking candidates who might be stronger in later votes. Criticisms of caucuses as arcane, inconvenient, and inaccessible to many demographics, especially working parents, also fall into this category. Speed gets less open attention, and its practical importance is greatest for the chattering class, but Monday night's frenzy showed many Americans expect quick returns and find delays annoying if not downright fishy.

Speed, accuracy, and equity are all good things, but they're competing values where the primary process is concerned. For example, many like the idea of online voting, which would be a huge boon to speed and equity. Responses would be instantly recorded in a centralized database, and voter turnout would undoubtedly increase if "turning out" consisted of opening an app on your phone.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Online voting hasn't been widely adopted, however, because the risk to accuracy is enormous. The chance of hacking or simple malfunction, as seems to be the situation with the Iowa Democratic Party's adoption of an app to collect caucus results, is too great. Experts predict it will be decades before online voting will be reliably secure, if indeed it ever can be.

All of this is to say: We can't get everything we want. We can't have a perfectly fast, accurate, and equitable primary process because those values are often incompatible. Still, once we set aside television's ceaseless appetite for content and hone in on what the voting public needs, it strikes me as undeniable that speed is the value to sacrifice. If we have to wait a day — a week, even — to get results from a fair, trustworthy voting process, so be it. We can wait a little. Delays, if anticipated, need not be suspect.

And don't worry, the TV pundits will adapt. I'm sure CNN's week-long countdown graphics will be stupendous.

Bonnie Kristian was a deputy editor and acting editor-in-chief of TheWeek.com. She is a columnist at Christianity Today and author of Untrustworthy: The Knowledge Crisis Breaking Our Brains, Polluting Our Politics, and Corrupting Christian Community (forthcoming 2022) and A Flexible Faith: Rethinking What It Means to Follow Jesus Today (2018). Her writing has also appeared at Time Magazine, CNN, USA Today, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, and The American Conservative, among other outlets.