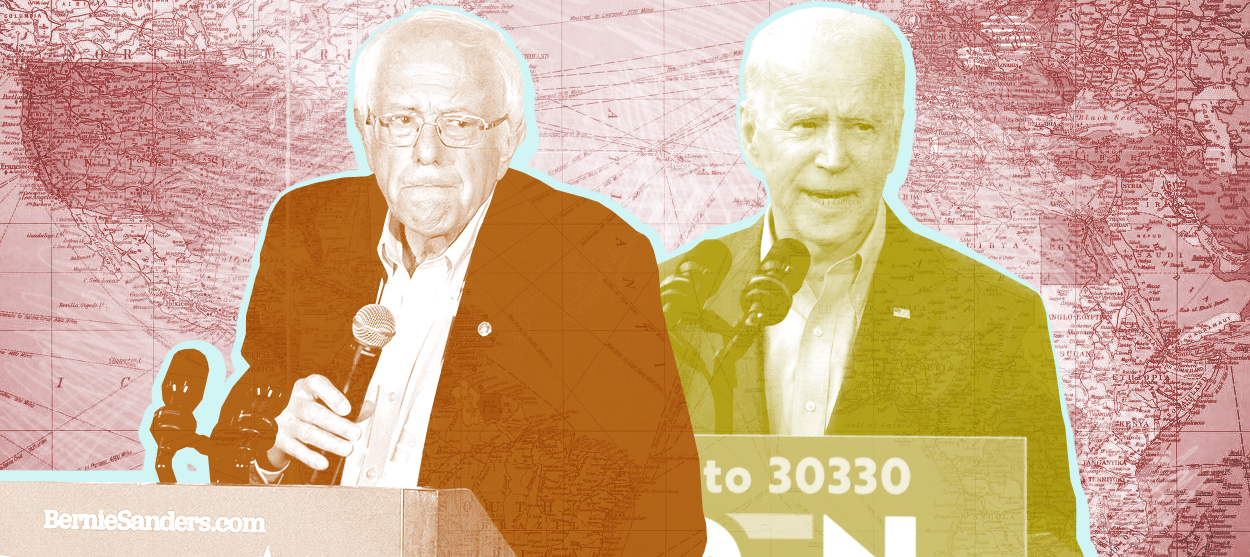

Biden and Sanders yearn for a bygone world

Here is the common ground in the 2020 contenders' foreign policies — for better and for worse

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

After today, the Democratic contest may well be a two-man race between Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders. While Elizabeth Warren may and Michael Bloomberg certainly will have the resources to press on to the convention should they so choose, any dreams that an inconclusive first ballot would lead to one or the other being anointed by the party over the two delegate leaders are unlikely to survive contact with political reality. Unless one or both front-runners falter badly, and Warren and/or Bloomberg significantly exceed expectations for winning delegates, for the rest of the race they might as well be on the sidelines.

The choice between Biden and Sanders appears to be extremely stark. In no area is that clearer than in foreign policy, where the president has the most personal latitude, but which frequently factors only peripherally and superficially into clashes between candidates and into the voters' own decision-making.

And yet, looking below the surface, there is a deep common assumption between the two men, one that grows less and less valid as the world continues to change. That assumption is the centrality of American power.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The differences between Biden and Sanders are blatant and obvious. Biden is a paid-up member of the American establishment and has been deeply involved in every major foreign policy decision for the past 30 years. Sanders, by contrast, has been a vociferous critic of American foreign policy for the same period, and has rarely if ever been in the room where key decisions are made. Most notably, Biden strongly supported the Iraq War, while Sanders strongly opposed it.

But Biden is not the across-the-board liberal hawk that he is sometimes caricatured as. Biden supported the Iraq War — but he opposed the first Gulf War, opposed Bush's surge of troops to stabilize the country, and during his years as vice president led the effort to extricate America from the Iraqi morass on the best terms possible. Biden supported the Afghan War, but counseled President Obama against sending more troops to that country to try to win a counterinsurgency campaign. He was a fierce proponent of humanitarian intervention by NATO in the Balkans, even though the campaign had no authorization under international law — but within the Obama administration he opposed the intervention in Libya, though that adventure had similar premises. He can be rightly described as both an idealist and a realist: someone who believes in using American power to make the world a better place, but who is skeptical that every applications of it will work (though perhaps less-skeptical than he should be of his own brainstorms, like partitioning Iraq in three).

Biden, in other words, does not harbor the illusion that America can shape the world as we see fit by a simple act of will. He recognizes that power has limits. But he does still view America as the single global superpower, with a responsibility to improve the world wherever it reasonably can.

That is his fundamental commonality with Sanders, who is not quite the advocate of "come home, America." Sanders is far more skeptical that America has actually deployed its power to make the world a better place, not only in practice but also in intent, particularly when it involves the use of force. In his view, we haven't just made mistakes, but have committed grave crimes and placed ourselves on the side and in the service of some of the most despicable regimes on the planet. There's a reason why Sanders has been a stalwart leader in opposing America's support for Saudi Arabia's war in Yemen. He strongly opposes America's militarized foreign policy, our alliances with countries like Saudi Arabia, our confrontational policies toward countries like Iran, and our dereliction in the fight against nuclear weapons.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In principle, though, Sanders can imagine an America that lives up to a tougher moral standard. And when he thinks it is doing so, he hasn't been opposed to using American power for moral ends. The lone opponent of the Afghan war was not named Bernie Sanders. Like Biden, though far less-influentially, Sanders supported intervention in the Balkans. And while he opposed military action to depose Libya's Moammar Gadhafi, he went on record to call for regime change by non-military means. Most importantly, Sanders regularly expresses confidence that the world could be made a more peaceful and harmonious place if America were more committed to international cooperation and global institutions. Biden is a big believer in those institutions as well, and has been his entire career.

I do not mean to minimize the differences between the two men. But I want to highlight what they do have in common to point out what their perspective leaves out. What if the key foreign policy question of our era isn't how best to use American power for the world's good? What if the question is how to handle a world in which American power is in serious relative decline?

There is ample evidence that this is the case. China's economy is already larger than America's in Purchasing Power Parity terms, and it is rapidly achieving peer competitor status or even dominance in certain high technology fields. China's importance has already driven a wedge between America and its allies, as can be seen from the pushback in Europe against the Trump administration's efforts to keep Huawei's 5G technology out of American-allied countries. Meanwhile, the credibility of our NATO security guarantees wears thinner and thinner, not only because of Trump's evident disdain for the alliance, but precisely because America has bigger fish to fry in the East. Last but far from least, it's less and less clear that America could win a major conventional war against China in Asia.

The Trump administration's response to these developments is encapsulated in his call to "Make America Great Again," and instantiated in his military buildup, his trade war with China, his cozying up to India, and his efforts to woo North Korea. In none of these areas have his efforts born notable fruit. But they are responses within a framework that prioritizes addressing decline.

What about Biden and Sanders? While unquestionably cognizant of the scope of China's rise, Biden has repeatedly mocked those who call China a potential peer competitor. He continues to view the world through the lens of natural American leadership that needs to be exercised responsibly, with powers like China and Russia brought to accept the rules of an American-ordered system for both trade and security. Sanders' views on China focus on the potential harm from free trade to American workers — a vital topic — but doesn't grapple fully with the fact that the damage from granting Permanent Normal Trading Relations status to China has been done and that we now face a fundamentally much more competitive environment. His views on where to take our Asian alliance system are largely unknown.

As a consequence, when they confront Trump in the general election, Biden and Sanders each face a very real risk of sounding like echoes of a bygone era.

Democrats don't have to ape Trump's aimlessly jingoist puffery to engage the era that we are actually in. Ironically, the third and fourth candidates in the race — Elizabeth Warren and Michael Bloomberg — have, in very different ways, done a better job than either Biden or Sanders of grappling with the meaning of our era.

Warren's call for economic patriotism and her determination to use the battle against climate change for competitive economic advantage are two pillars of her approach, which is as much about building up American strength and independence as it is about restoring equality. Bloomberg is clear-eyed in a different way; his determination not to call Xi Jinping a dictator, and his accurate emphasis that China is going to be the dominant player in any fight against climate change can be understood as rational accommodations to a world where China is a peer competitor, and America has to treat it as such.

The point is not that America shouldn't try to improve the world — of course we should. But any foreign policy worth promoting must be based in reality. The core reality of our era is America's relative decline. We can take steps to slow it, to compensate for it, and to adapt to it. But first we have to recognize that it is happening, and the ways in which it renders the debates of the past 30 years obsolete, regardless of who was right.

It would be helpful if, going forward, the two frontrunners for the nomination debated their differences with that in mind, rather than living in the past.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Noah Millman is a screenwriter and filmmaker, a political columnist and a critic. From 2012 through 2017 he was a senior editor and featured blogger at The American Conservative. His work has also appeared in The New York Times Book Review, Politico, USA Today, The New Republic, The Weekly Standard, Foreign Policy, Modern Age, First Things, and the Jewish Review of Books, among other publications. Noah lives in Brooklyn with his wife and son.