How to bail out the oil industry without destroying the planet

Hundreds of fossil fuel companies could go bankrupt if lawmakers don't take action — but should we?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

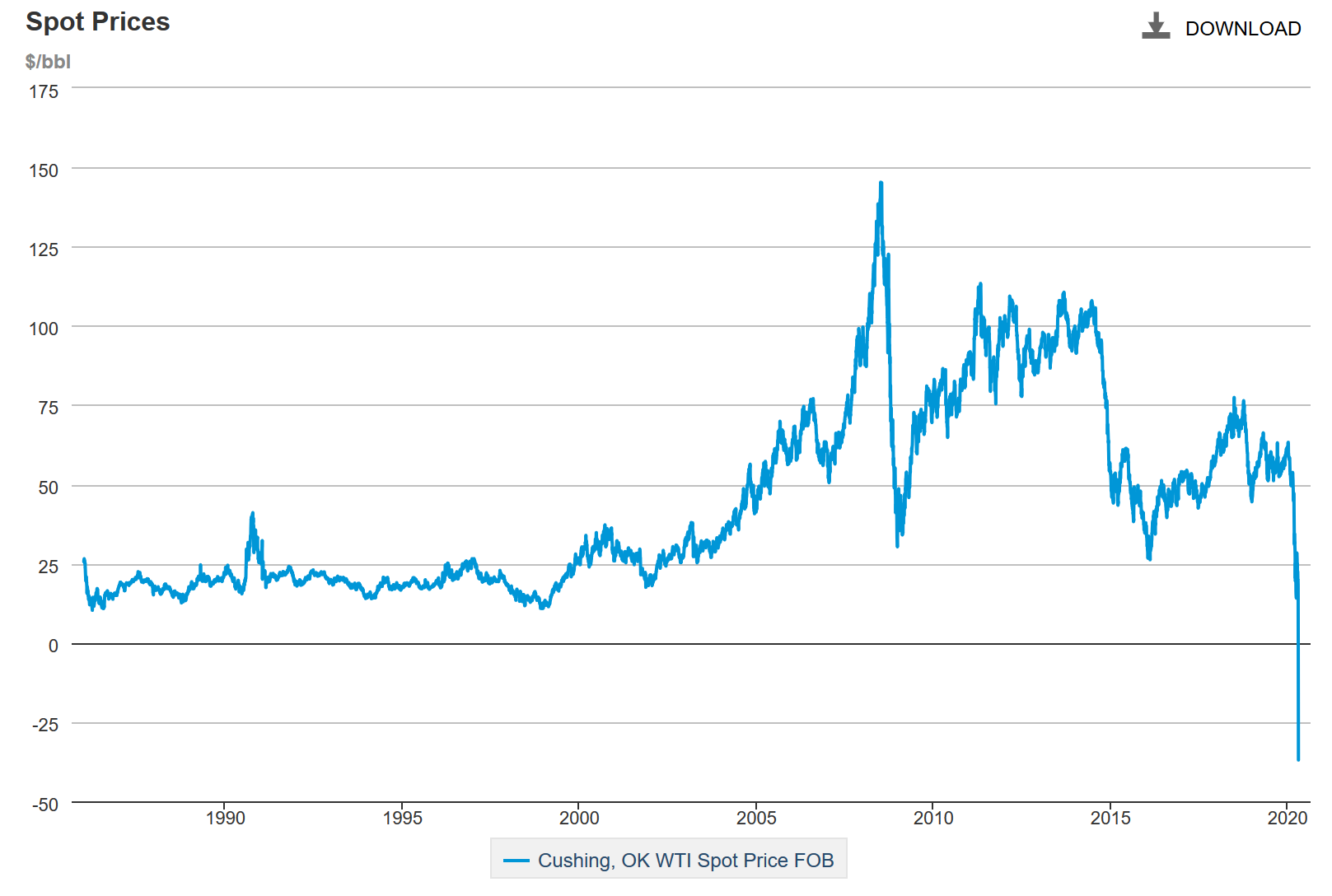

For a brief spell on Monday, one of the most watched metrics for crude oil prices went negative. Oil producers were literally willing to pay people almost $40 a barrel at one point to take their product. It was the first time in history that had happened.

Trading has recovered since then, but crude oil prices remain crushingly low, and are now a genuine existential threat to the U.S. oil and energy sector. That's inspired demands for a federal bailout of the industry, including from President Trump himself — along with a chorus of opponents saying the industry isn't worth saving. But depending on what we mean by "bailout," this could be a moment of historic opportunity for the climate change movement.

First, though, what in God's name just happened?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The last decade's boom in North American shale oil production was a mixed blessing: It created a bunch of jobs and made America a net exporter of oil, but it also flooded the international market with supply. Meanwhile, demand for oil was being eroded by gains in energy efficiency, green energy, and green tech. Much of the remaining global supply is controlled by state-run oil producers like Saudi Arabia and Russia, who dump supply into the market based on geopolitical strategy as much as market signals. This big ramp up of supply relative to demand led to a price crash several years ago, from which the industry has been slowly recovering.

Then came the coronavirus pandemic. The stay-at-home orders and economy-wide lockdowns, both in the U.S. and around the world, sent that already-soft demand for oil into a nosedive. If massive parts of society are no longer working, commuting, flying, etc, they have no need for fuel. Then Saudi Arabia and Russia got into a price war, and ramped up production in an effort to sabotage both the U.S. industry and each other. President Trump managed to broker a detente, but the agreed-to production cuts were not nearly enough to balance the lower demand, so prices kept plunging.

Of course, if the supply of oil is far outpacing demand, all that excess oil has to go somewhere. And there's a whole market for oil storage that smooths out these price falls. The problem is, the current glut is so extreme that this market has literally run out of physical storage. There's just nowhere to put the oil anymore. So when the oil storage contracts for the month of May settled early this week, oil producers literally found themselves having to pay the storage people to take the oil and figure out what to do with it. Hence the price plunge into negative territory.

We're past the May contracts hump now, and the situation for June looks marginally better, so oil prices have recovered after Monday’s dive. But they're still below $15 a barrel, which is just insanely cheap.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The other key thing is that the U.S. oil sector is buried in debt. Oil production, and especially shale oil production, is a capital-intensive industry, and it's only becoming more so as all the easy-to-get oil is tapped out. As impressive as the domestic oil boom was this past decade, it had to be fueled by a ton of borrowing. The industry now owes $86 billion that's coming due between now and 2024 — a lot of which is risky, low-quality debt. Pipeline companies owe another $123 billion over the same period.

Even before the coronavirus crisis, the financial industry was not happy about this, and a lot of oil company bankruptcies seemed likely. Now the situation seems genuinely apocalyptic: U.S. producers need almost $50 a barrel to be profitable. Below $40 a barrel, 15 percent of U.S. oil companies wouldn't make it past a year, and another 24 percent likely wouldn't make it past two, according to reporting by CNN. At $20 a barrel, basically everyone is seriously losing money, and over 500 U.S. producers would have to file for bankruptcy by the end of 2021. At $10 a barrel, you're looking at over 1,000 bankruptcies. Just to remind you, we're currently under $15 a barrel.

No one knows how long the coronavirus pandemic and the necessary social distancing will last. But given that most projections put a vaccine at well over a year away, oil prices staying under $20 until the end of 2021 seems entirely possible. In which case, the U.S. oil industry is going to get absolutely decimated.

That brings us to the question of how, or even whether, to save it. Congress has passed big aid programs for both big businesses and small, but the oil industry falls into a weird no man's land in between. As I said, President Trump himself has begun pushing a bailout specifically for that sector. And his critics are pushing back: We need to get global carbon emissions to zero by 2050, the U.S. oil industry is one of the biggest obstacles to that effort, and it’s a dying industry that irresponsibly loaded up on debt anyway. So why squander the money on it?

Here's the thing, though: The problem with the oil industry is that it's run by people who don't want it to die. But what if it was run by people who did recognize the need to ultimately dismantle fossil fuel production? If the federal government just straight-up nationalized the industry in the near future, it would have almost three decades to transition its workers and physical capital into green sectors, wind down oil production to zero, and figure out what to do about plastics and petrochemicals. Among progressive climate activists, there are burgeoning proposals to do just that. And right now, thanks to the coronavirus crisis, the oil industry has never been a cheaper bargain. Haliburton's stock is down by two-thirds. ExxonMobil's is down by 38 percent. Every energy company on the S&P 500 could be bought out for a grand total of about $700 billion — or roughly one-third of what the U.S. government just spent on the CARES Act.

As I said, it seems likely the oil industry's value won't recover much by early next year. Assuming the Democrats retake the government in November, they should absolutely make this gambit part of a larger Green New Deal effort.

In the meantime, an oil industry bailout in the here and now, depending on how it's structured, could also lay the groundwork for that. If the federal government just gives the oil industry straight cash or cheap loans, that's obviously not good. But lawmakers are also discussing a deal whereby the government takes ownership of the surplus oil that's in excess of demand, or it gets oil industry stock in exchange for aid. In that case, the federal government could get to decide when — or if — that excess oil ever gets consumed at all. And if the shares the government gets from the industry are voting shares (a key and critical point), it could begin to wield influence over big oil's corporate governance. Then, assuming Democrats win in November, they can use that power as a stepping stone to grab up the rest of the industry.

In other words, if progressives and Democrats play their cards right, an oil industry "bailout" could help save the global climate.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'Cartoons Artists take on a girlboss, a fetching newspaper, and more

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’Talking Point Reform and the Greens have the Labour seat in their sights, but the constituency’s complex demographics make messaging tricky

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred