The false prophets of growth

The last decade was proof austerity doesn't work — has anyone paid attention?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In 2009-10, when most of the world was still at the depths of the Great Recession, two economics papers quickly swept through the policy elite in both Europe and the United States — one by Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff, and the other by Alberto Alesina and Silvia Ardagna. They both purported to show the benefits of austerity policies — basically, raising taxes and cutting government spending — to cut the national debt. Reinhart and Rogoff showed that in several countries, growth seemingly slowed markedly when the national debt-to-GDP ratio topped 90 percent, while the other two suggested that austerity, especially cutting spending, would increase growth.

At the time, they were swimming against the tide of policy — the U.S. had just passed the bank bailout and the Recovery Act stimulus. However, their arguments quickly got a hearing. Peter Coy of BusinessWeek wrote: "Alberto Alesina is a new favourite among fiscal hawks … In April (2010) in Madrid, he told the European Union's economic and finance ministers that 'large, credible and decisive' spending cuts to rescue budget deficits have frequently been followed by economic growth." The Washington Post editorial board cited the 90 percent figure in 2013 as a reason to stay the course with austerity. Rogoff himself wrote in 2012 that "very high debt levels of 90 percent of GDP are a long-term secular drag on economic growth that often lasts for two decades or more."

Politicians in both parties advanced the austerity narrative — especially the Democrats. Republicans have long been pure opportunists on this issue, blowing up the budget deficit when in power and then demanding cuts when not, but Democrats idiotically thought it was the responsible thing. In 2010, President Obama's Director of the Office of Management and Budget Jack Lew wrote, "just as families and businesses across the nation have tightened their belts, so must the federal government."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

There was only one big problem: Both of these papers, and the austerity narrative generally, turned out to be comically slapdash. Alesina and Ardagna jiggered their data set to select for countries that were already growing strongly before they tried any austerity, or were small and could export their way out of trouble — neither of which would apply to a large country like the U.S. that was already in recession. Reinhart and Rogoff, hilariously, had a spreadsheet error that badly dented their correlation and, more importantly, had mixed up cause and effect. It is low growth that generally causes a high debt-to-GDP ratio, not the other way around. Whoops!

The last 12 years of economic history show how things turned out. Though the papers were discredited, the political damage was done. The U.S. did indeed choke down a great deal of austerity in the years after the crisis — tightening overall budget balance even more than austerity-crazed Europe between 2010 and 2013, by one estimate. The result was exactly the nightmare of drastically lowered growth the proponents of austerity said we needed to avoid.

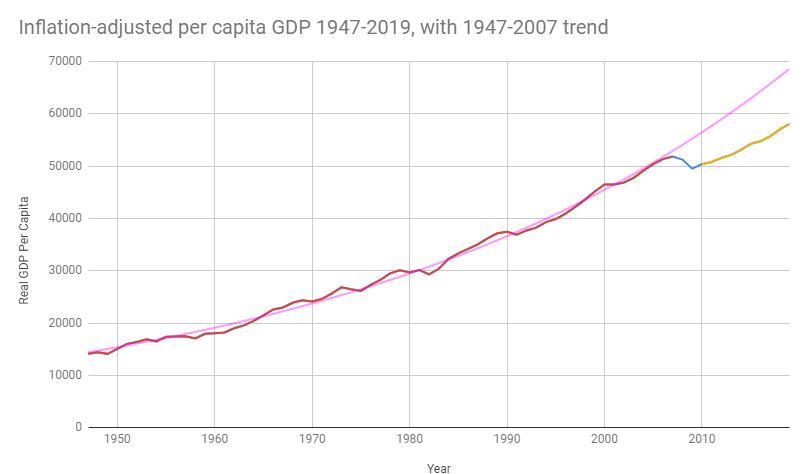

Here I have charted inflation-adjusted per-person GDP, with the years up to the Great Recession in red, the post-crash "recovery" in yellow, and the 1947-2007 exponential trend line in pink. (This is just an update of something economist J.W. Mason did in 2017.) It is obvious that growth slowed dramatically after the crisis.

Average annual per capita growth from 2008-2019 was a mere 0.97 percent, less than half of the 1947-2007 average of 2.2 percent. Even if we leave out the 2008-09 crash years (arguably inaccurate since the pre-crisis average includes many recessions too), the figure is only 1.6 percent, more than a quarter below the previous rate. The fastest growth recorded was in 2018 at 2.4 percent, after Republicans passed a fiscal stimulus in the form of a huge tax cut — though the effects were limited because so much of the benefit went to the rich, who are unlikely to spend it. All told, per capita output in 2019 was roughly 15 percent below the previous trend line — something like $3.3 trillion in 2012 dollars (the year the St. Louis Fed uses to chain its price index to, for statistical convenience), greater than the output of California and Virginia combined. And now, of course, the economy is collapsing due to coronavirus.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In neoliberal terms, this is an unimaginable catastrophe. In 2012, William McBride wrote an analysis for the neoliberal Tax Foundation twisting his handkerchief about how economists have supposedly found "a tax increase of 1 percent of GDP lowers real GDP by about 3 percent after about two years" (though his paper has also been heavily criticized). Yet the post-2007 period has seen a decrease in the growth rate of 56 percent. Indeed, the whole point of all this austerity was to keep the output numbers going up fast, only for the opposite to happen. All that wealth, going utterly to waste! It's enough to make Free Trade Baby Jesus cry.

Conversely, as Mason argued, there is every reason to think even today that most of that gap could be recovered with vigorous economic stimulus (once the coronavirus crisis has passed). Keynesian models predicted that austerity would strangle the economy, but that implies that aggressive spending to stimulate output would undo some or all of the damage — after all, that's precisely what happened during the New Deal and especially the Second World War.

Now, a caveat is in order: For a country as rich as the U.S., growth as such should not be the only objective for policymakers. What the resulting output is spent on is equally important — any economic stimulus should obviously be directed towards slashing greenhouse gas emissions to fight climate change. We also should be instituting work-reduction policies to give Americans more free time, which all things equal would reduce per-capita output. Every part of this country has serious room to improve. Nevertheless, the first task of any Democratic government should be to obtain full employment and production, because that will protect the political foundation to do anything else.

Even so, all this history casts serious doubt on the neoliberal pro-growth pose. Presumably if the concern were genuine, economists would double-check their spreadsheets before hurriedly slapping together an argument for cutting the budget deficit while unemployment is at 10 percent. As Michał Kalecki argued, "obstinate ignorance is usually a manifestation of underlying political motives."

That's part of why it's now so troubling that presumptive Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden is now surrounding himself with economic advisers like Bruce Reed and Larry Summers. Even before the austerity measures of the last decade, they were prime movers in multiple neoliberal disasters — welfare reform for the former, and deliberately lowballing the 2009 Recovery Act economic stimulus for the latter, to name just two of many examples. In 2010, Reed was appointed to head up the Simpson-Bowles National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility, which was created by Obama in order to generate austerity recommendations for Congress (after which he became Biden's chief of staff). All along the way, they and their neoliberal allies have been arguing that cutting regulations and taxes will unleash American entrepreneurs and grow the economy, and that growth in turn is supposed to be the solvent that dissolves class conflict: Rather than arguing about redistribution, we can just "grow the pie" and everyone will benefit.

Now, it just might be possible that at least some of the Democratic policy crew will find it difficult to maintain their prior stance. For decades they have posed as the tough-minded, realistic truth-tellers who will make the hard decisions to keep the economy growing — only for their ideas to create the worst economic performance since the early 1930s, and thence a series of disastrous electoral defeats for their party. Neoliberal austerity has been a neutron bomb both economically and politically. Indeed, Summers himself co-authored a paper in 2012 after leaving the Obama administration demonstrating that stimulus during a recession would pay for itself by increasing future tax revenue (though he often says things like that when out of government). It's easy to see why — throwing more than the entire output of California directly into the toilet, year after year, will certainly affect America's ability to pay the bills.

Should Donald Trump be defeated by the Democratic presidential nominee in November, the next president is going to have an ungodly mess on his or her hands. The economy will in all likelihood still be in serious trouble, and what to do about it will be the second item on the presidential checklist (after containing the almost surely still unresolved pandemic). If Biden, Summers and company want to really be the far-seeing wise men who will keep America's economy trucking into the next century, and keep from being swept in the 2022 midterms, they need to ditch austerity and start drawing up a Green New Deal.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred