The making of a coronavirus conspiracy theory

What climate change deniers and coronavirus skeptics have in common

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

For most of my adult life, I have believed there would come a point when climate denialists would have to give up the game. I thought the plain facts of rising coastal waters, widening drought, and growing human misery would at long last force them to stop resisting efforts to mitigate climate change and start working in earnest for effective solutions.

The COVID-19 pandemic has made me realize I was wrong.

"Climate change is going to be exactly like this," my colleague Ryan Cooper correctly asserted in March, "only on a much longer time scale." What we're also finding is that the American coronavirus backlash looks a lot like the resistance to climate-friendly policymaking — only on a much shorter time scale.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In both cases, conservative elites attempt to muddy the scientific consensus in order to raise the hackles of rank-and-file voters against government action. In both cases, it is the poor and minorities who will feel the brunt of that inaction. And in both cases, many of those same elites will find they cannot fully protect themselves from the fallout of their choices.

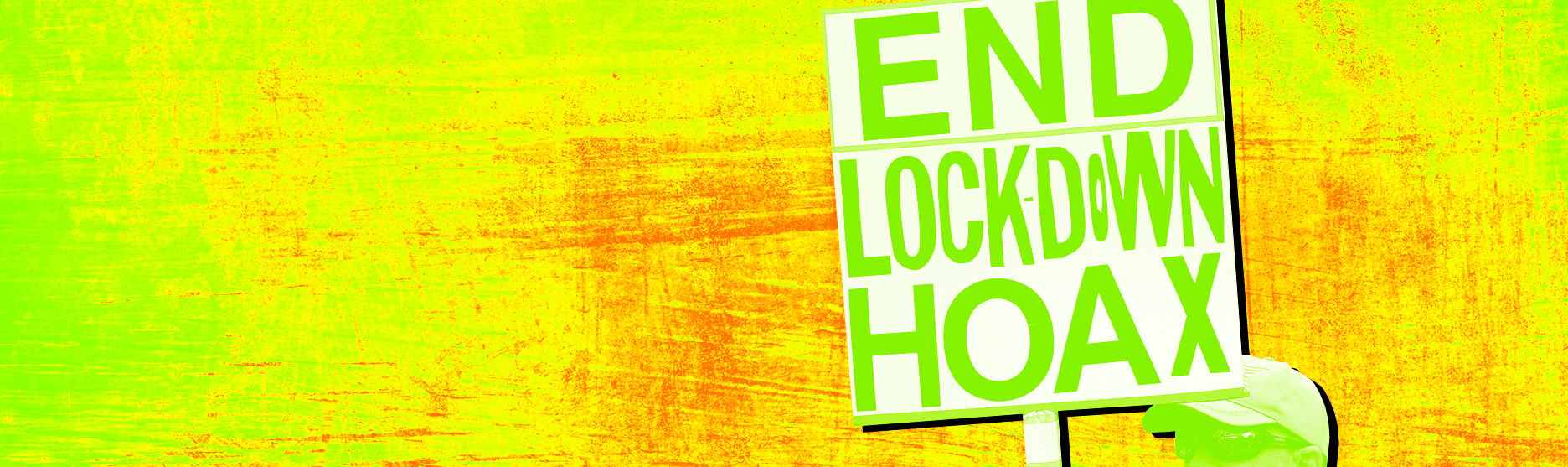

Denialism has many tactics. One is to generate a controversy over the known facts where none really exists. (The term "hoax" has been bandied about a lot when it comes to both climate change and coronavirus.) Skeptics routinely offer up lists of scientists who challenge the consensus that the climate is changing, and that change is due to human activity. That means instead of taking action, real experts end up spending their time and energy defending that consensus, getting bogged down in debate when they could be formulating and executing a response to the crisis. Similarly, coronavirus deniers have offered up questionable research and conspiracy theories to contest expert-driven guidelines on social distancing — and to outright deny that the coronavirus is a threat. Sometimes they even throw multiple, contrasting arguments out to the public. The point is not to inform or be consistent, but to generate noise and skepticism among the wider citizenry.

Another tactic is to kill the messengers — and their message. President Trump has proposed deep cuts to the Environmental Protection Agency, curtailing climate-related projects at NASA and ending grants aimed at helping coastal residents adapt to rising waters. Similarly, the administration has shelved guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on how local governments can safely reopen their economies amid the pandemic, and Arizona's governor is cutting off scientists from data they can use to track coronavirus and predict how it will affect the state. This tactic doesn't change or slow the devastation of the the threats, but it does make it more difficult for both experts and the public to comprehend the dimensions of the challenge they pose.

A final tactic of skeptics is to normalize the devastation. Denialists make the case that the Earth's climate goes through hot and warm stages anyway — ignoring the experts' conclusion that humans have greatly and dangerously accelerated that process. Likewise, Trump and his allies are making the case that Americans must learn to accept the risk of COVID-19 infection as part of everyday life. But normalization suggests those risks are inevitable. That isn't true, or not entirely so. America's rising number of infections is the result of choices made by Trump and other policymakers.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The results of such denialism are the same, no matter the topic: Poor and minority people across the country and the world will face the greatest risks, and often pay the highest personal costs. Climate change is already depriving many of those people income, food, and shelter. Similarly, the coronavirus pandemic in America is disproportionately ravaging the African-American population and the working class. Rather than help those workers, leading Republicans are focusing their efforts on making sure they can't sue their employers for creating unsafe workplaces.

Profit is a main driver of denialism. Oil companies have shelved reports on the effects of climate change rather than do the difficult work of making changes to their lucrative businesses. And Trump and many of his Fox News allies refused to deal with the growing pandemic until the stock market started falling.

But denialism is unsustainable. The virus is increasingly encroaching on Trump's inner circle — his valet has contracted the virus, as has Vice President Mike Pence's spokeswoman. And so the White House has expanded coronavirus testing for staff members even as the president has publicly downplayed the need for broader testing to help safely restart the economy. There is no place completely safe from the threat.

Sooner or later, climate skeptics may be forced to learn the same lesson. In the contest between reality and make-believe, reality usually wins — but it can take a really long time, with untold costs along the way. Tradeoffs may be needed in both the climate change and coronavirus debates. Those tradeoffs should be rooted in facts and reality. By obscuring and normalizing ugly truths, the denialists make it more difficult for us to effectively confront all the threats we face.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Joel Mathis is a writer with 30 years of newspaper and online journalism experience. His work also regularly appears in National Geographic and The Kansas City Star. His awards include best online commentary at the Online News Association and (twice) at the City and Regional Magazine Association.

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred