Voters won't accept the 2020 election results — no matter who wins

How rejecting election results became an American political norm

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

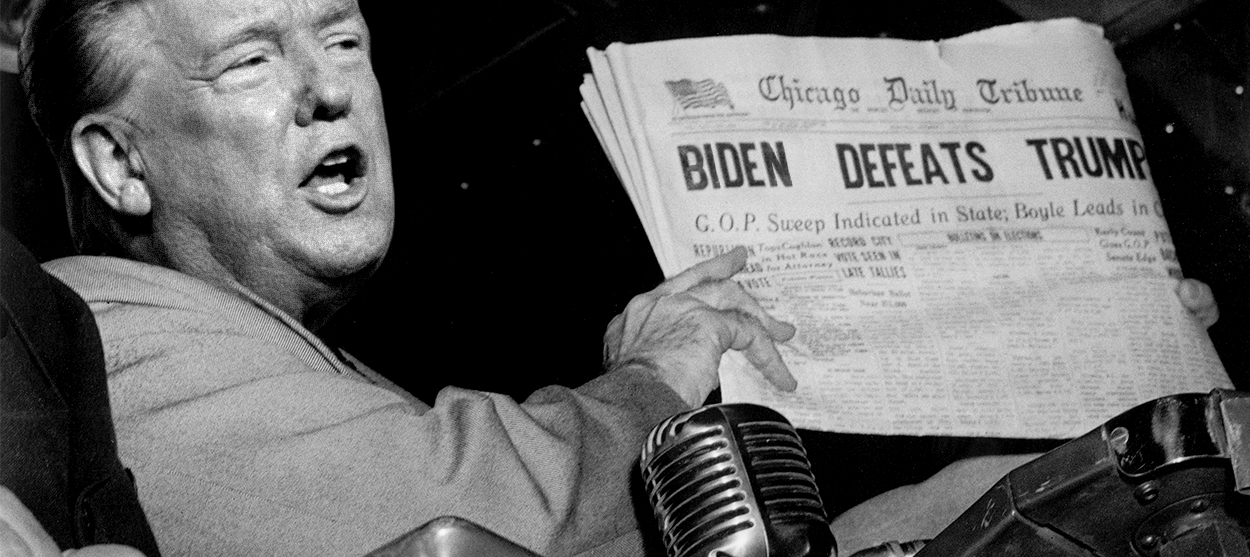

During the last month and a half or so of the 2016 presidential election, meta-arguments about how Donald Trump would respond to his own (inevitable in the estimation of most observers) defeat became more important than any of the apparent issues in the campaign. Would he accept the results? What this question was supposed to mean — accept how? psychologically? — was far less important than the response it was meant to elicit, which is to say, a negative answer that would in turn become the pretext for thousands of fear-mongering articles like this one.

There were strong and weak theories about what form the Celebrity Apprentice star's loss would take. The most hysterical prognosticators, including his Democratic opponent, argued that he would attempt to destroy democracy itself. (How exactly he would go about this was never very clear: Would he attempt a coup via Twitter?) Others suggested that his entire campaign had been a marketing ploy all along, the teaser trailer for a coming right-wing populist media empire in which Trump would present himself as a kind of president-in-exile to millions of delusional fans, endlessly agitating for recounts and hawking branded water.

In these endeavors, few if any observers expected Trump to receive support from the institutional GOP, which had, with few exceptions, remained ambivalent about its own presidential nominee. This was the implicit bargain between Trump and Republican leadership. Had he lost, he would have been excommunicated; his swift political rise and equally rapid fall would have been the occasion for an endless I-told-you-sos, both from those who have come to consider themselves his supporters and in what are now the wild hinterlands of #NeverTrump conservatism. (Whether casting him into outer darkness would have been as easy as congressional Republicans and the editors of conservative publications would have liked is an interesting question.)

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

We all know what happened instead. After months of harangue from his opponent and the media about the existential importance of resigning himself to an assured defeat, Trump won, and Democrats spent the next four years very publicly doing most of the things they had predicted would ensue if things had gone the opposite way. His presidency was regarded as invalid from the moment he took the oath of office, for reasons ranging from his being an agent of the KGB to the very serious crime of not actually withholding aid to a minor East European nationalist regime.

Four years later, Joe Biden is openly fantasizing about a scenario in which the praetorian guard dispatches the senescent emperor from his palace. Whether the former vice president remembers the similar (and ultimately pointless) discussions from 2016 is an open question, but not an especially important one. What matters more is the current barely concealed relish at the prospect of the current president being removed from the White House by force. Never mind the fact that these lurid speculations exist alongside equally lunatic assertions that we are living under a Trump-led military dictatorship: What they reveal about the American attitude toward presidents and their legitimacy is far more interesting than their internal coherence.

There's little reason to think any of us are prepared to accept the results of the upcoming election, at least not unequivocally. This unwillingness has less to do with the candidates themselves or the circumstances surrounding individual elections than with the chiliastic terms upon which presidential campaigns are waged in this country. These are not quadrennial contests between two parties offering competing sets of prudential solutions to the nation's problems: They are spiritual wars in which the righteousness of one side and the iniquity of the other are both blindingly obvious to all persons of good will.

This is why George W. Bush's first presidential victory was dismissed by mainstream liberals as the result of either counting-related malfeasance or a plot by the Supreme Court or both, and why his re-election must have had something to do with rigged electronic voting machines. It is also why millions of us convinced ourselves that Barack Obama must have been born abroad and that Trump was working for the Russians.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

These conclusions, absurd and conspiratorial as they are, follow effortlessly from the twin premises that every presidential election is an all-or-nothing contest between good and evil and that the sovereign will of the people is inviolable. This is why even when genuine support for the “wrong” side is acknowledged — not every vote is the result of a fraudulent ballot or a tweet from a Russian troll bot — we insist upon delegitimizing the voters in question. The 47 percent and the basket of deplorables are mirror images of each other, and not only because simple arithmetic suggests that they must refer to many of the same voters. Rather than accept the idea that millions of our fellow Americans have simply drawn different conclusions about the candidates, which might call into question either the presumed stakes of our elections or the wisdom of self-government, we insist upon pushing them outside the boundaries of politics: people who vote in bad faith and (at least implicitly) should not be regarded as contributing to the actual democratic process. The plainer alternative explanation — that elections are messy things and voters frequently irrational and almost never deserving of the flattery bestowed upon them by candidates from both parties — is one that we have become mysteriously incapable of considering.

Beginning as we do from such premises, it should be no surprise that none of us are prepared to “accept” any political outcomes that we find objectionable. So far from subverting our democracy, disregarding the results of our elections has become one of the most reliable norms in American politics.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Matthew Walther is a national correspondent at The Week. His work has also appeared in First Things, The Spectator of London, The Catholic Herald, National Review, and other publications. He is currently writing a biography of the Rev. Montague Summers. He is also a Robert Novak Journalism Fellow.