One glaring question about the police killing of Elijah McClain

Why is someone who was already restrained being given ketamine?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The police killing of Elijah McClain in Aurora, Colorado, did not attract much national attention when it happened this past August. But McClain's death has drawn wide outrage in recent weeks; a petition for a new investigation of the officers responsible drew more than 2 million signatures, and Colorado Gov. Jared Polis (D) has directed the state's attorney general to review the case.

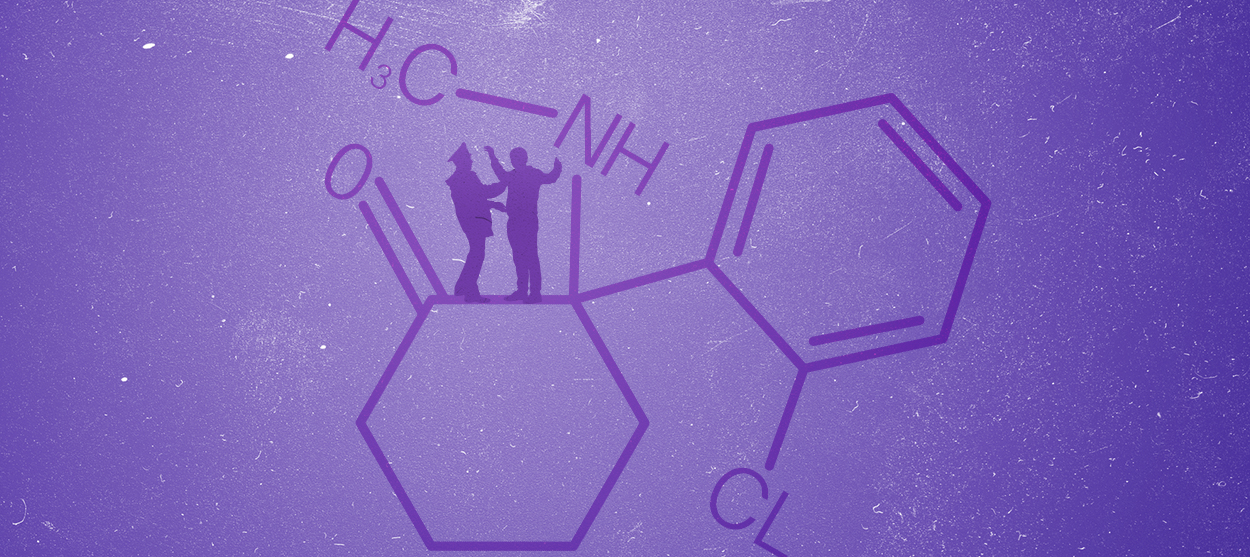

Here is one question the Polis administration should give particular scrutiny: Why was McClain given ketamine, a strong tranquilizer often described as a date rape drug, during his deadly encounter with the cops? And why has ketamine become a policing tool in the first place?

Much of the story of McClain's death is horribly familiar: Like Trayvon Martin, he was walking home from a convenience store with an iced tea. Like Tamir Rice, the police were summoned to accost him for noncriminal behavior: in this case, wearing a ski mask (McClain was anemic and often donned extra layers to keep warm) and waving his arms, perhaps in time to music in the headphones he reportedly was using. Like Philando Castile, he attempted to assert his rights, telling officers (per their account), "I have a right to go where I am going." Like Walter Scott, the police decided he was resisting arrest. Like George Floyd and Eric Garner, he protested, "I can't breathe" when officers applied pressure to his neck. Like too many other names to mention, he was Black and unarmed.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But the ketamine element is not familiar. Subjected to the chokehold, McClain briefly lost consciousness. After coming around, the police claimed, he began struggling again — though it is difficult to imagine how this behavior could have posed multiple armed officers any threat given that McClain was already handcuffed. Nevertheless, Aurora Fire paramedics who had been summoned to the scene because of the neck restraint "injected McClain with ketamine while police personnel held him on the ground," Sentinel Colorado reports.

McClain ended up hospitalized, suffering cardiac arrest on the ride there. He was visibly bruised and eventually declared brain-dead. Six days after he was stopped by police, his family took him off life support, and he died.

The ketamine dose McClain received is not stated in the autopsy report, which notes instead that his blood ketamine concentration was at a normal therapeutic level, well below levels seen in ketamine overdose deaths. "Of note, in terms of a fatality," the report says, "the dosage administered or ingested is not as important as the resultant concentration of the drug in the blood." However, one comment heard in the body camera footage suggests the dose may have been 500 milligrams. That approaches the dose of 700 milligrams that would produce up to 25 minutes of full surgical anesthesia for someone of McClain's reported weight of 140 pounds. It is also markedly higher than doses recommended for pain relief, which raises the question of whether the dose was intended to produce a second unconsciousness (as opposed to conscious lethargy or calm).

If the ketamine contributed to his death — which the autopsy report declines to say — perhaps McClain had an "idiosyncratic" reaction, a possibility the report allows. Or perhaps the cardiac arrest in the ambulance wasn't so idiosyncratic, as cardiovascular and respiratory symptoms are among ketamine's common side effects. Or perhaps the dosage was too large, as a doctor with knowledge of McClain's medical history could have determined better than paramedics shooting tranquilizer into a handcuffed man already pinned to the street.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

We should learn the answer if we can, because this use of ketamine as a tool of law enforcement isn't unique. An Aurora Fire Department press release said ketamine is "routinely utilized to reduce agitation" during arrests. This is permitted because Aurora has one of the "90 fire departments and emergency medical service agencies across Colorado [...with] waivers from the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment to use ketamine to treat excited delirium," the Denver Post reports.

"Excited delirium" is a controversial thing: It is not recognized as a condition by the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders nor the World Health Organization's International Classification of Diseases. It is easy to see how many of its symptoms — like shouting and being disoriented — could simply be a stress response to police brutality. And even if excited delirium is not, as critics allege, mere cover for police misconduct, it does not follow that roadside diagnosis and administration of heavy medication by paramedics (sometimes at the encouragement of police with no medical expertise) are appropriate.

But diagnosis and administration do happen, and not just in Colorado. An article in the May 2017 issue of EMS World approvingly imagines a scenario, apparently intended to be familiar to readers, in which paramedics agree they should give ketamine to a distraught man who has been tased, handcuffed, and physically restrained by police. In cursory research I found reports of paramedic use of ketamine for "excited delirium" while working with police in Florida and Texas, as well as numerous reports of other sedatives being used and discussion of which drug is best (ketamine seems to be increasingly favored).

The best data comes from Minneapolis, where Floyd was killed. A 2018 city report revealed not only that ketamine was used during arrests but that paramedics used it at police request. Officers "repeatedly requested over the past three years that Hennepin County medical responders sedate people using the powerful tranquilizer ketamine, at times over the protests of those being drugged, and in some cases when no apparent crime was committed," the Minneapolis Star Tribune reported.

Some of those injected, like McClain, were already handcuffed. Some were strapped to ambulance stretchers. In some cases, the ketamine produced heart or respiratory failure. Some people had to be resuscitated or intubated. Some recipients were enrolled in a study of ketamine use without their consent. In at least one case, a paramedic justified administering ketamine for the sake of the research: "[W]e're doing a study for agitation anyway, so I had to give her ketamine," the paramedic said. The woman given ketamine had requested an asthma pump after police sprayed her with mace. She stopped breathing after being tranquilized and had to be revived.

Before the city report, Minneapolis had no department rules prohibiting police "prescriptions" of ketamine, even though the department manual labeled it a date rape drug. After the report, a Minneapolis Police Department order directed that officers "shall never suggest or demand EMS Personnel 'sedate' a subject. This is a decision that needs to be clearly made by EMS Personnel, not MPD Officers."

How was this behavior permitted in the first place? In theory, it shouldn't be, Cato Institute legal scholar James Craven told me. The sort of ketamine use we see in McClain's death is a civil rights violation by any reasonable understanding of the term. "The Fourth Amendment prohibits the use of excessive force, and the right to be free from forcible injection is absolutely a recognized and protected liberty interest," Craven said. "Courts will balance this with an 'objective reasonableness' test determining if administration was reasonable given the circumstances," he added. If, as with McClain and many of the Minneapolis cases, "you've got someone who is already restrained, using ketamine is not going to pass that test both because there are safer alternatives and because there is really no reason to be using a sedative to begin with."

But in practice, it is difficult to stop police from openly inviting or tacitly approving ketamine as a type of excessive force. Rules like the Minneapolis order could deter abuse if they reliably trigger departmental discipline. A statutory ban to the same effect would be a stronger caution, as might setting legal prerequisites for paramedic use of sedatives during police encounters.

Meanwhile, when police do recommend ketamine, our old friend qualified immunity often ensures they escape legal consequence. Qualified immunity says police are only liable for civil rights violations that abrogate "clearly established law," a highly specific requirement the Minneapolis rule won't satisfy. "Courts only consider [breaking qualified immunity] if there's been another case, in their jurisdiction, where someone was sued for very similar conduct, and that conduct was found unconstitutional," Craven said. As long as qualified immunity stands, a departmental rule is toothless for redressing wrongs already committed.

That means police are protected from being sued for recommending a tranquilizer dose during an arrest. It means Elijah McClain was given ketamine in the police encounter that killed him because its use in that context is explicitly permitted in his state — and its abuse is nearly impossible to hold to account.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Bonnie Kristian was a deputy editor and acting editor-in-chief of TheWeek.com. She is a columnist at Christianity Today and author of Untrustworthy: The Knowledge Crisis Breaking Our Brains, Polluting Our Politics, and Corrupting Christian Community (forthcoming 2022) and A Flexible Faith: Rethinking What It Means to Follow Jesus Today (2018). Her writing has also appeared at Time Magazine, CNN, USA Today, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, and The American Conservative, among other outlets.