An anxious poll-watcher's guide to 2020

Has the shock of 2016 ruined our ability to trust polls forever?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

On the morning of Nov. 9, 2016, millions of bleary-eyed Americans woke up and wondered, what just happened? It's a question pundits, pollsters, crying people on the subway, Trump's own family, and Hillary Clinton (in her not-so-subtly-titled memoir, What Happened) have tried to get to the bottom of over the last four years, and one that jittery, invested bystanders like myself are reminded of with each new poll that shows President Trump's challenger, Joe Biden, seemingly miles ahead. Right, I think with every confirmation of the Democrat's double-digit lead. Can't fool me. I remember how this one ends.

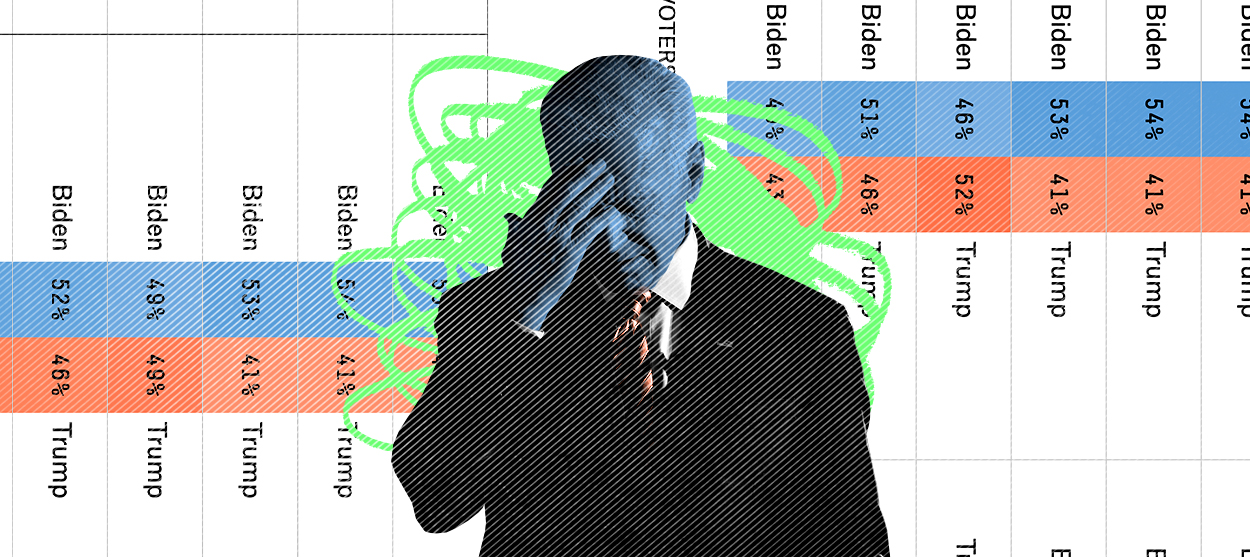

Unlike some of my colleagues, I'm still unsure of a Biden victory. Many other Americans are in the same boat: Even though Biden leads the polls, a plurality of registered voters still think Trump will beat him in a repeat of the upset we all experienced in 2016. Personally, I've found myself anxiously ping-ponging between different interpretations of the 2020 polls: that the race is closer than it looks, or that Biden will still win, even if state polls are underestimating Trump to the extent that they did in 2016. Is GOP pollster Frank Luntz right that this is Biden's election to lose? Has anyone thought to ask the psychic monkey what it thinks? Like many Americans who no longer have faith in the polls, I'm terrified of getting burned again: What, and who, can we trust this time around?

In the run-up to November 2016, there had been near universal agreement that Trump wasn't going to win; "it would take video evidence of a smiling Hillary drowning a litter of puppies while terrorists surrounded her with chants of 'Death to America'" in order for her to lose, was a memorable favorite claim. In truth, though, the 2016 national polls actually weren't all that inaccurate; The New York Times and FiveThirtyEight both predicted Clinton would win the popular vote by 2 to 3 points, and she won by 2. The bigger issue — and the reason something like The New York Times' hive-inducing election needle showed Clinton with a 95 percent chance of winning at one point on Nov. 8 — was that key battleground polls had underestimated how Trump would perform, infamously failing to adjust for the local educational demographics. "Some of these errors," The Upshot's Nate Cohn wrote in a review of what went wrong in 2017, "will be easier to fix than others."

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Being wrong is, quite simply, an established part of polling — even pollsters will tell you that. "[P]olls are imperfect instruments," Sean Trende, the senior elections analyst at RealClearPolitics, explained to The New Yorker. "When you trust the polls, you need to trust them for what they are, which is not oracular, perfect insights of wisdom but, rather, a good metric of where things stand right now." And while pollsters have certainly made adjustments since 2016, that doesn't eliminate the possibility of other problems arising in the process, or making new, different mistakes now. "There's nothing pollsters can do, for example, if undecided voters break for one candidate in the final hours," Cohn explains. Even a "big, easy fix" like weighting for education in 2020 isn't a sure thing: "There's a possibility that the problem wasn't, in fact, that pollsters weren't weighting by college education," Trende suggested. "...[M]aybe it was something else. We don't know what it is. The 2018 [midterm] results give me some pause." Great.

Trende points to one example, which is that Trump's job approval rating is running a few points higher than his vote share at the moment: "Who are these people that approve of the job he's doing but aren't going to vote for him?" he asked. One hypothesis that has been debunked is the myth of "shy Trump voters," people who supposedly lie to pollsters about who they're supporting. What's more plausible is something called a "differential partisan non-response," which The Economist explains is when "the candidate you support is doing badly, you are less likely to answer a pollster's call."

Notably, though, even adjusting for partisan non-response, "our election model assigns Mr. Trump only a one-in-ten chance of winning the election," The Economist goes on to write. Which serves to remind us that 2020 is not 2016: While Clinton's lead over Trump waxed and waned, Biden has remained between 6 and 10 points ahead of Trump consistently. One big difference this year, too, is that "undecided voters are probably less likely to give [Trump] the benefit of the doubt than they were four years ago," The Washington Post's Philip Bump writes; for instance, while Trump won voters who disliked both candidates by 17 points in 2016, Biden leads that group now … by 20 points. There are also significantly fewer undecided voters left on the board in 2020, probably between 3 and 6 percent, much smaller than Trump's average polling deficit.

Over at FiveThirtyEight, a spiffy graphic illustrates that at the time of writing, Biden wins 86 out of 100 election simulations, while Trump wins a mere 13 (there's a tie once). But off to the side of the data, the website's "Fivey Fox" mascot cheerfully reminds the reader, "Don't count the underdog out! Upset wins are surprising but not impossible." While 86 percent might sound like it's a sure thing for Biden, Trump's 13 percent chance of winning re-election is about the same chance as a couple that has exactly three kids having three boys; rare, but hardly unheard of. What's more, there are still a long 21 days to go before the election; this time four years ago, then-FBI Director James Comey hadn't even yet reopened the investigation into Hillary Clinton's private email server. There's still plenty of time for a surprise video to emerge of Joe Biden drowning puppies while surrounded by "Death to America"-chanting terrorists. Non-polling-related factors could also come into play in deciding who the next president is: voter suppression, for example, or a contested election.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Even so, want to know the simplest answer? Quartz says that so long as "national polls are close, say within five points, really anything can happen." Between Sept. 28 and Oct. 11, RealClearPolitics' average had Biden up by a margin of 10.2.

I'll let you do the math.

Jeva Lange was the executive editor at TheWeek.com. She formerly served as The Week's deputy editor and culture critic. She is also a contributor to Screen Slate, and her writing has appeared in The New York Daily News, The Awl, Vice, and Gothamist, among other publications. Jeva lives in New York City. Follow her on Twitter.