Democrats need a better counter to 'originalism'

If the Democratic Party can't articulate and sell a legal philosophy to their voters, the progressive project will fail

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

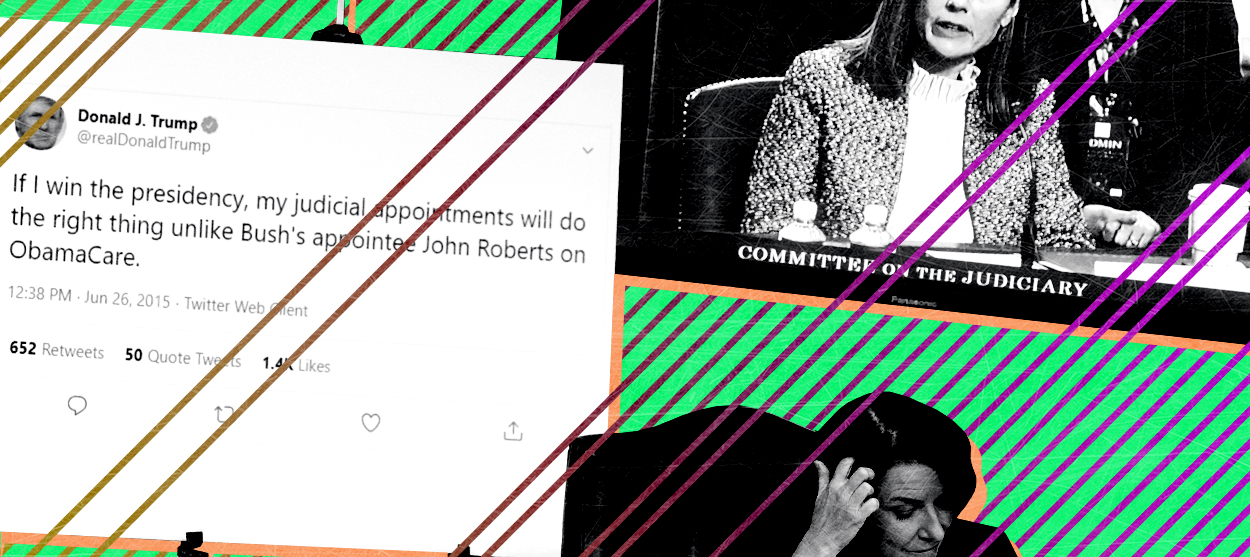

Yesterday was the third, and apparently final, day of hearings for President Trump's latest nominee to the Supreme Court, Amy Coney Barrett. With the initially sharp public opposition to her confirmation softening in some surveys, Democrats on the committee have spent the week both assailing the absurdity of rushing a pick through just weeks before the election, and using Barrett's extremist judicial philosophy to highlight the policy catastrophes that might ensue if she replaces liberal stalwart Ruth Bader Ginsburg on the court.

It was actually quite a disciplined, if painfully repetitive, series of performances. And the Democratic gambit here is understandable: Treating the Barrett confirmation as an extension of the policy stakes in the 2020 election and seeking to get her on the record siding with deeply unpopular policy positions held by the deeply unpopular President Trump is probably the smartest play available to them. She is at least a superficially appealing figure, and boycotting the proceedings or seeming gratuitously confrontational might not have played well with voters. But they are also missing a huge opportunity to articulate a coherent progressive-Democratic alternative to Barrett's self-professed and profoundly radical judicial philosophy of "originalism."

For Democrats on the Senate Judiciary Committee, these confirmation battles are about discrete policy issues, primarily reproductive rights, gun control, and the Affordable Care Act. Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.), the ranking Democrat on the committee and, at 87, a living, breathing advertisement for Senate term limits, provided a perfect example of how Democrats approach these nomination fights in her prolonged opening statement on Day 2 of the hearings.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Feinstein asked if Barrett would "agree with Justice Scalia's view that Roe can and should be overturned by the Supreme Court?" and whether the government has "compelling interest in preventing a rise in gun violence." Her interest in the Affordable Care Act was driven entirely by the case currently before the Supreme Court, and leaned heavily on the policy implications of tossing it out. She kept asking Barrett, again and again, her views on particular decisions or cases, only to be met with carefully crafted stonewalling.

From Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) to Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) and Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.), committee Democratic senators leaned hard into this strategy. They brought stories of people from their states whose lives would be destroyed without the Affordable Care Act. They noted that the process was rushed and that it appears Barrett is being hurried onto the bench in time to strike down the ACA. Or as Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.) argued, "We're here because in the middle of a deadly pandemic, in the middle of an ongoing election, Senate Republicans have found a nominee in Judge Barrett who they know will do what they couldn't do, subvert the will of the American people and overturn the ACA and overturn Roe v. Wade."

These things all share the virtue of being true, and they carry a message that might reach, through viral video clips (normal people do not sit around all day watching Senate hearings), the 99 percent of voters who are unversed in the legal niceties of these debates. But they also leave the distinct impression that Democrats have no principled ideas connecting their policy positions. And the failure to articulate that through-line has consistently led to rank-and-file Republican voters understanding the stakes of these nomination fights better than their Democratic counterparts.

That asymmetry grants Republicans a massive advantage in the court wars that goes beyond their utter shamelessness in creating new norms and rules and then setting them aside the second they become inconvenient. Originalism, as preposterous as it might be as a judicial philosophy, and as haphazardly as it has been applied even by its most ardent defenders, makes sense to ordinary people who aren't well versed in constitutional law, most of whom have been taught from a young age to revere the Constitution as a glorious document akin to some kind of secular scripture. As Barrett stated, "I interpret the Constitution as a law."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

It's a claim that makes less and less sense the more you think about it. The U.S. Constitution is an extraordinarily brief document. You can read the whole thing, and all of the amendments, on an elliptical machine during a mid-length workout. It contains no guidance whatsoever for virtually any problem confronting an enormous, and enormously complex, society of 340 million people. Adhering to such ideas has the practical effect of protecting unrestrained capitalism and white supremacy against the rapidly declining fortunes of the Republican Party and a country being remade by changing demography.

While marveling at the contradictions of originalism is great fun, and complaining about the Federalist Society's extraordinary influence in today's legal system is fine as far as it goes, it doesn't fill seats on the Supreme Court or offer Democratic voters a reason beyond this or that policy to get animated about the courts. Why aren't Senate Democrats capable of advancing an alternate theory of the Constitution? Surely there must be more to it than protecting certain past decisions with which Democrats happen to agree, or protecting a handful of laws that are already on the books?

That theory is out there and it is called "living constitutionalism." As David Strauss defines it in his short, readable book The Living Constitution, living constitutionalism regards the Constitution as a document "that evolves, changes over time, and adapts to new circumstances, without being formally amended." Rather than being "dead, dead, dead" as Barrett's mentor Antonin Scalia once put it, the Constitution is a fundamentally elastic creation, and judges should be able to use precedent and common law to informally adjust it without going through the Constitution's arduous and mostly impossible amendment process. That change cannot, as Strauss argues, take place completely outside of legal or constitutional principles, but should be grounded in "certain limits and only in ways that are rooted in the past."

As Stanford University Law Professor Pamela Karlan argues, there are some instances where the Constitution is crystal clear. No one under the age of 35 can become president, for example. There is little need for interpretation in those cases. But for the most part, the Constitution provides very few guidelines for the most vexing social and political problems of the day. Karlan also has a pithy rejoinder to Barrett and her ilk's obsession with what the authors of the Constitution were thinking. "Why should we care about that? Maybe the framers wanted us to interpret the words in light of our experience and our understanding."

Living constitutionalists rightly regard originalism as a straitjacket that constricts the policy options available to contemporary leaders, and has the cumulative effect of trapping the United States in a series of catastrophe loops, like the inability to address gun violence due to a particularly strained "originalist" reading of the 2nd Amendment, itself a painfully ambiguous, dreadfully written mess. Despite ample evidence that the Constitution's authors had no intention of giving every individual American the right to kit themselves out in more firepower than a British regiment, Barrett's allies on the Supreme Court have imposed an absurd regime of limitless violence on this country, repeatedly overturning state and local laws and letting an epidemic of shootings continue indefinitely.

Why don't Democrats pull a page from the impeachment playbook and designate some of their time in these hearings to a genuine constitutional expert like Karlan, who could corner Barrett on the true, terrifying implications of strict originalism and also begin the arduous process of getting all members of the Democratic coalition on the same page about the philosophy? Nine minutes of listening to her talk about a progressive judicial philosophy would be worth more to the long-term fortunes of Democrats and progressives than passing 5-minute speaking slots around to a functionally random assortment of Democratic senators to make the same points over and over again.

Barrett was always likely be confirmed no matter what, but in the long run, if the Democratic Party can't articulate and sell a legal philosophy to their voters, the progressive project will end up just as dead as the Constitution was to Antonin Scalia.

David Faris is a professor of political science at Roosevelt University and the author of "It's Time to Fight Dirty: How Democrats Can Build a Lasting Majority in American Politics." He's a frequent contributor to Newsweek and Slate, and his work has appeared in The Washington Post, The New Republic and The Nation, among others.