How politics became a battle for your attention

Sloganeering has come to direct policy — not the other way around

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Political slogans are as old as democratic politics — by which I mean mass politics, conducted on a national scale, with politicians campaigning for votes over vast physical spaces with the help of modern technologies of communication.

But as with everything else in our digital age, sloganeering has now gone viral, spreading beyond campaign buttons, bumper stickers, and yard signs to shape the policies pushed by sitting presidents, empower officeholders to elevate their personal brands, and give a booming megaphone to activists seeking to enact sweeping change.

Whether the trend is good for democratic politics is another matter.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Political sloganeering has its roots in advertising: The effort by businesses selling things to win the attention of consumers. The tag line is key — the clever, memorable idea conveyed in a few simple words that gets lodged in the brains of potential purchasers, becoming identified in their minds with the product and the company that makes and sells it, increasing the reach of the brand and thereby also increasing its sales.

Slogans first entered American presidential politics during the early 20th century. Among the most effective early slogans was FDR's promise of a "New Deal" for the American people, introduced as part of his 1932 campaign for the White House. It caught on in a big way, becoming universal shorthand for a revolutionary expansion of the role of the federal government during the Great Depression and beyond.

Over the decades that followed, campaign slogans ranged from the comically banal ("I Like Ike") to the evocative but ultimately vacant ("The New Frontier"). But their character shifted in a subtle but significant way with Lyndon Johnson's promise to wage a "War on Poverty." Introduced during Johnson's 1964 State of the Union address, the phrase wasn't a campaign slogan so much as the summation of an intention that at the time it was uttered didn't yet possess policy content. Its purpose was to mobilize public opinion behind the Johnson administration's efforts to alleviate poverty in the hopes of pushing Congress to foot the bill.

Once the administration had adopted the slogan, policies that fit the tag line had to be devised. Reducing poverty was now a war. Wars were supposed to be won. Though like the "War on Drugs" that would come to center stage during the Reagan administration two decades later, the "War on Poverty" became a moniker used to cover a diverse range of programs and initiatives that didn't amount to anything resembling an actual war. It was certainly never "won." As the decades rolled on, even measuring progress or improvement in the general direction of victory became dicey.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

It didn't matter. Presidents had learned how to brand their agendas with snappy catch phrases that quickly got lodged in people's attention, shaping the way journalists and ordinary citizens talked about politics and public policy.

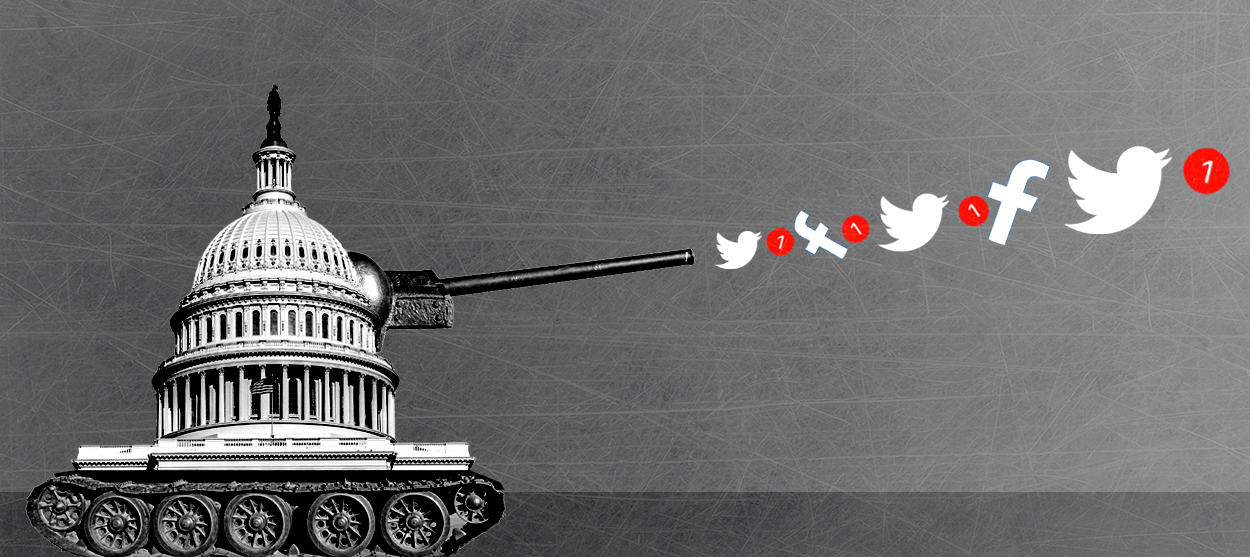

But that's nothing compared to what we've seen over subsequent decades. As Charlie Warzel points out in a smart New York Times column on the prescient writings of author Michael Goldhaber, the internet and social media have massively democratized the capacity to colonize our attention. No longer limited to businesses hocking products or presidents and parties pushing policies, every politician, every activist, and even every amateur pundit on Twitter, Facebook, and Reddit now aims to get noticed, to win the battle for attention. And the most effective way to do that is to coin a pithy phrase — a slogan, in other words, that distills everything down to a memorable few words that will instantly sell the author and his or her idea to a vast public.

Though "sell" isn't quite the right word. The old adage of the marketing executive — no publicity is bad publicity — is the highest principle at work in viral sloganeering. Take the most notorious catch-phrase of the past year: "Defund the Police." As a policy proposal, it's atrocious — facile, unpopular, inflammatory, irresponsible, unserious. But it traveled extremely well. Within days of it emerging late last spring as a talking point and hashtag for activists fighting racism and police brutality, the national debate on the topic had been transformed by the slogan.

To be clear: This doesn't mean it has been embraced. On the contrary, it has polarized the debate on how to respond to problems with policing, giving conservative opponents of change a handy real-life target instead of a straw man to batter, and creating knotty problems for more mainstream progressive officeholders and aspirants who now have to distance themselves from the proposal while not sounding disengaged from the underlying issue.

A dismal failure, then? Not at all. The slogan transformed the national conversation! It was hugely impactful! Engagement was off the charts! We can't stop talking about it!

If politics is about democratic self-government — a community's effort to enact policies that concretely improve its members' lives and ameliorate injustices — it's hard to see how the undeniable viral potency of "Defund the Police" had anything other than a negative political effect, since in addition to giving ammunition to the right, it may well have contributed to the weaker-than-expected showing for Democrats in House, Senate, state, and local races around the country in 2020.

But if politics is about enhancing the power of left-wing activists to command attention — to get them seen and heard, to shape the national conversation, even in a way that ultimately yields electoral and policy setbacks in the short term — then the slogan was remarkably successful.

That's the politics of sloganeering in a nutshell, and it obviously works exactly the same way on the right, transforming the ability to grab attention (positive or negative) into the most salient measure of political power, regardless of ideology. In such a political ecosystem, generating outrage and disgust can be as potent as inspiring respect or adulation. And the worst thing of all — the most egregious fault by far, the surest sign of political powerlessness — is to inspire boredom or indifference.

Welcome to a world in which the ultimate — and maybe the only — political contest is the battle to win your finite attention.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.