The U.S. welfare state is messy. That's not a bad thing.

Mitt Romney's child benefit proposal is a trap that undermines other anti-poverty programs

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A lot of progressives are excited about Mitt Romney's proposed child allowance that would replace a number of existing anti-poverty programs. The Week's own Ryan Cooper describes it as a chance to "clean out some of the policy muck cluttering up the American welfare state."

But what if it is the politically "messy" aspects of the U.S. welfare state that allowed it to survive and even expand in the face of Republican presidents, the Senate filibuster, and often hostile courts?

Despite Reaganism and despite unified GOP control from 2003 to 2007 and 2017 to 2019, most of the U.S. welfare state not only survived but, in total inflation-adjusted dollar terms, is far larger in 2021 than it was in 1980 before Reagan took office. Maybe those insider Democrats are wilier and more skilled than some of their pundit critics recognize.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Political scientists derisively refer to the "iron triangle" of congressional committees, the federal bureaucracy and interest groups protecting government programs — but parceling out the U.S. welfare state in pieces to different committees with their own vested interests preserving each program has often been key to their survival in the face of right-wing Republican attacks.

Perhaps the clearest example is food stamps, a program born and expanded due to a messy alliance of farm interests and largely urban anti-poverty interests that, over time, semi-absurdly became the main focus of the U.S. Department of Agriculture budget. In 1995, Republican Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich wanted to gut the Food Stamps program (now named SNAP) by handing the money over to the states — exactly the play that eviscerated the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program the following year. But he failed because the alliance of farm interests with anti-poverty groups blocked his move. A key opponent was his Senate counterpart, Republican Senate Majority Leader Robert Dole, an otherwise staunch conservative who had helped move the Food Stamps program into the Agriculture bill back in 1973 because it served the interests of farmers in his native Kansas.

Years later, with unified Republican control under Trump, when the final farm bill was approved in 2018, liberal anti-poverty advocate Robert Greenstein would describe it as "solid bipartisan compromise that maintains and modestly strengthens SNAP," because those alliances still held. In fact, SNAP has become the largest income transfer in our system for many families, growing from a program covering just 12 million families with a microscopic $14/month in benefits in 1973 to covering 35.7 million in 2019 with an average family benefit of $258/month — with some larger families receiving more than $1000 monthly.

School lunch subsidies, overseen by the House Education and Labor Committee, are backed by similar political coalitions, but adds in the subcontractors supplying and even running school lunch programs, education reformers, and the lobbying clout of the 55,000 dues-paying members of the School Nutrition Association, the "lunch ladies" who corral support for the $24 billion in child nutrition programs each year. One measure of the value of school lunches is that a new pandemic benefit transfer will send families as much as $1,700 per student for school meals missed from the beginning of the pandemic through the end of this school year — highlighting the money saved from family meal budgets normally.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

While Republicans largely succeeded in gutting traditional cash welfare (AFDC, renamed Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF)), funding for the non-working poor via SSI and SSDI disability money, governed by the Subcommittee on Social Security and supported by the range of disability rights advocates, has grown significantly. In fact, the disability rolls grew almost in lockstep with the decrease in welfare rolls — although the mostly older population on disability is not generally the same as those who left TANF. But federal disability pays far better monthly than AFDC ever did for the 13 million non-elderly recipients who did qualify in 2021.

The other large income transfer to low-income families, the Earned Income Tax Credit, was born in the 1970s as an alternative to exactly the kind of Universal Basic Income plan that Andrew Yang argued for in the Democratic primaries and that Romney — to a very limited extent — is now promoting with his child allowance proposal. Reagan would also push an expansion of the EITC in his 1986 tax bill as a substitute for raising the minimum wage. Later, Democratic legislative leaders would leverage "pro-work" coalitions to massively expand the EITC under Bill Clinton and then under Barack Obama.

The result was that an EITC maxing out at $851 to a family under Reagan is now worth as much as $6,660 to a family in 2021 — with 26.4 million households qualifying for the EITC. A less-than $10 billion budget item in the 1980s grew to an estimated $73.1 billion this past year, the largest anti-poverty income transfer program in the budget. Notably, the EITC has had the advantage over its semi-rival minimum wage policy of being able to be increased through budget reconciliation in the Senate — seen again this year as Biden pushes for another EITC expansion in his coronavirus relief bill while facing the likely exclusion of his minimum wage proposal due to filibuster rules.

These successes don't mean the U.S. welfare state's more complex mechanisms always work perfectly. For example, low-income housing support is, unfortunately, a disaster. Decades of battles from the New Deal onwards has left a splintered set of programs, each with their own anti-poverty, real estate, and associated interests sustaining them, with arbitrary paths to access that leave most low-income families without any support for paying their rent. This is even more enraging given that the government subsidizes homeowners via the home mortgage deduction so much more than renters. But 5 million low-income households do get rental assistance through those programs, as much as $1,000 per month for families in the costliest cities. So, even housing can be counted as a modest success, with the budget for rental assistance programs increasing from less than $2 billion yearly in the mid-1970s to over $46 billion today (five times as much if you account for inflation).

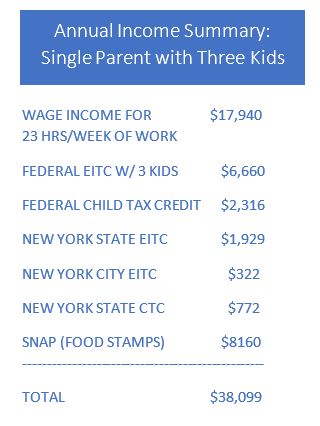

Put all of these programs together and, as the chart shows, in combination with state and local add-ons to the EITC and the current Child Tax Credit (CTC), a parent with three kids making $18K in New York City will get more than $20,000 in additional payments from the government if they work 23 hours per week at a minimum wage job. If they qualify for Section 8 housing subsidies, that could easily bring the total government aid to $32,000 per year — a pretty healthy welfare state that needs improvement but is underestimated by some progressives.

Which brings us to Romney's proposal to expand and "streamline" the welfare system around a child allowance payment. The CTC was born in 1997 as a sop by GOP leaders to "pro-family" advocates in the party — and the initial CTC was anything but an anti-poverty program since it was available only to better-off families with a significant tax liability. Only tactical alliances with those "pro-family" conservative groups and compromises amidst the economic crises of the early 2000s — and then again in the 2008 financial crisis — made the CTC partly refundable, phasing it in as families earned more money. Romney's proposal is to eliminate the CTC and a range of existing welfare programs, including limiting the EITC, to provide a $3,000 benefit for all children. The problem is that those cuts to other anti-poverty programs, in the name of being "revenue neutral," means many households, particularly those headed by single parents, end up worse off under Romney's plan. This is similar to Yang's more ambitious Freedom Dividend program that also would harm many low-income families by consolidating programs.

That's just the problem with the math of consolidation. The politics is potentially even more dangerous in making a child allowance the singular object of conservative attack. Senators Marco Rubio and Mike Lee, who have been two of the friendlier Republicans in making the Child Tax Credit more available to poor families, immediately attacked Romney's plan as "welfare assistance," highlighting likely future attacks on the program if the GOP retakes majority control.

While there is a wonky appeal to making the welfare state a "clean, efficient program that is legible to its recipients," the history of the messy alliances backing each program argues that consolidating welfare programs is more likely to dismantle needed coalitions and make such a program a concentrated target for conservative attack. Clearly, taking advantage of the current crisis to expand and improve the Child Tax Credit is a worthy goal — but not if it comes at the expense of other programs like the EITC, as Romney advocates. Those other programs have their own constituencies and are part of the often frustrating U.S. welfare state that has still survived in the face of multi-decade attacks by conservative political leaders. Rather than indulge in the aesthetics of policy design, any improvements in the U.S. welfare state should recognize and build on the alliances supporting current anti-poverty programs.

Nathan Newman is a writer and teaches Criminal Justice and Sociology at CUNY. His work has appeared in The Nation, The American Prospect, New York Daily News, and Dissent.