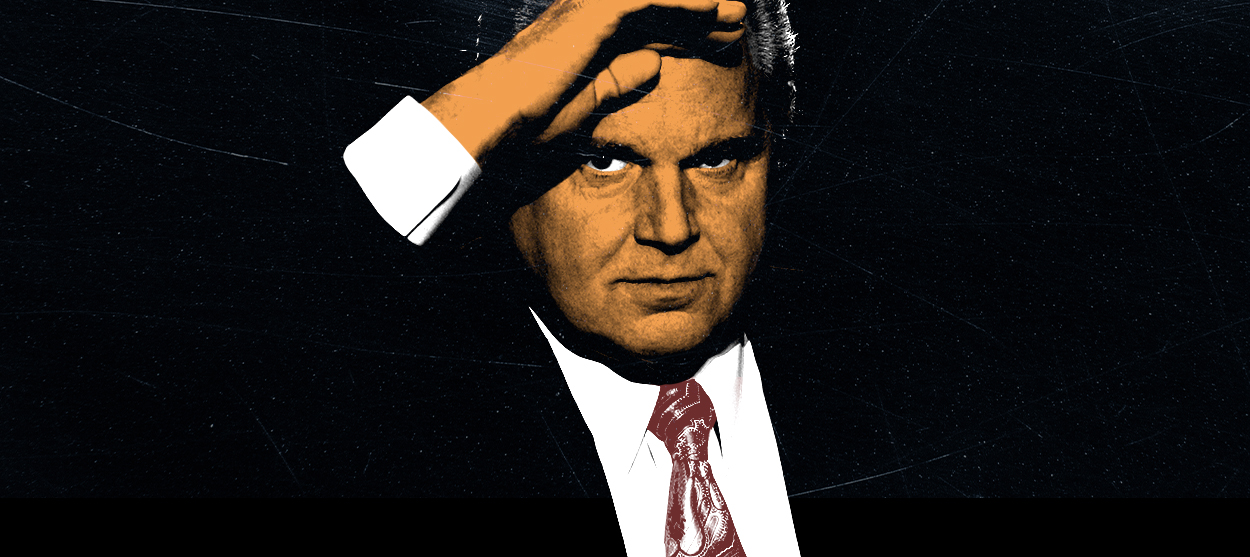

The chilling tributes to Rush Limbaugh

In banding together to offer solemn tributes to Limbaugh's life and influence, conservatives have shown us where they ultimately stand

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Less than a week ago, seven Republican senators joined with 50 Democrats in a vote to convict the former Republican president in his second impeachment trial. Just after the vote was completed, the Republican Senate minority leader delivered a 10-minute broadside against the man he'd voted to acquit, calling him an inveterate liar who deliberately stoked an insurrection against Congress. Three days later, the 45th president fired back, issuing a two-page statement blasting his party's leader in the Senate.

That was on Tuesday, when the Republican Party looked on the verge of fracturing into warring factions. But on Wednesday, something happened to bring the party together — to show that for all its deep differences, the GOP is united in venerating its true modern founder. From George W. Bush to Donald J. Trump, from think-tank wonks to alt-right trolls, Republicans agreed that Rush Limbaugh, who had just died after a battle with lung cancer, was a truly great man who incalculably advanced the cause of conservatism in America.

I can't really say I'm surprised by this outpouring of affection for the man who single-handedly invented right-wing talk radio and in so doing created a model of media that laid the groundwork for Fox News and a thousand broadcast, print, and online imitators. Still, there's something chilling about all the adulation. For Limbaugh didn't just promote conservatism. He debased it, vulgarized it, turning it into a vehicle for the flattering of prejudice and bigotry. A political persuasion that once spoke proudly of honor and virtue came to applaud a reactive carnival barker who couldn't be bothered with reasoning or crafting arguments in good faith and who proudly practiced a politics of shamelessness, insult, and mockery.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

At first, more thoughtful conservatives were unsure of exactly what to make of Limbaugh and his incredible success. They'd occasionally listen to his show in the car or in their offices and chuckle at the jokes and the tirades. But then they'd get back to work with ideas, refining philosophical arguments, advocating policies, developing rhetoric that could be deployed by presidents and those who aspired to high office. The conservative movement had always included broadcasters, publishers, and pamphleteers who did their work alongside intellectuals and scholars. The division of labor was encouraged. While the intellectuals spoke to elites within established institutions, the activist-entertainers communicated to the masses, whipping them into a froth of indignation that would ensure they showed up where and when it counted — at the ballot box on Election Day.

But Limbaugh succeeded on a scale never seen before. By the time I'd become one of those high-minded conservative intellectuals toiling at a magazine with a circulation of 30,000 — this was back in the early days of the George W. Bush administration — Rush's show reached millions. No one at First Things listened to it regularly. Why would we? We were busy trying to parlay the power of our arguments into influence among Republican politicians and the more educated and bookish members of the conservative movement. That was our role in the division of labor. Limbaugh was doing something different — keeping the foot-soldiers focused on the importance of winning and holding political power. That made him a vitally important ally, but he didn't speak to us. We weren't his audience. We had nobler means of reaching what we thought were the same ends.

In retrospect, what stands out about that period is how complacent we were about the stability of the arrangement. Conservative writers would go on at length about how ideas have consequences and how the inculcation of moral habits is crucial for the fostering of civic virtue — while simultaneously expressing no concern at all about millions of Republicans learning to think about politics from Limbaugh and his acolytes on radio and cable news. These writers were no less sanguine about the next generation of Republican intellectuals, reared exclusively on Limbaugh's degraded and demotic form of conservatism. Sure, they often skipped reading and writing serious essays and books in favor of honing their capacity to craft cutting insults that traveled well online and on Fox. But that wasn't a problem. The real intellectuals — the happy few — would keep doing their important work while the on-air talent did a better and better job of rallying the rank-and-file.

And that's what happened — at least until John McCain chose Sarah Palin as his running mate in the summer of 2008. From that point forward, all those restive millions of Republican voters who'd been showing up loyally to vote for candidates who were so much less rude and funny and ruthless and entertaining than Rush would crave and demand something much more like what he had taught them to love. Palin showed them that it was time to scrap the old division of labor. It was time for a new style of Republican politician — one with no interest in ideas or use for intellectuals, and even no need for or interest in expertise or competence at policy or governing. Politics could be entirely about driving one's opponents to distraction, a kind of partisan performance art.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

McCain lost his contest to Barack Obama, of course, depriving Limbaugh's dittoheads of their reward. Four years later, Republican voters failed to coalesce around a Palin substitute, though Michele Bachmann, Herman Cain, Newt Gingrich, and Rick Santorum each auditioned for the role before Mitt Romney ended up as the party's consensus choice. It was the last stand for normalcy in the GOP, and Romney's defeat was its last straw.

It took Limbaugh months to warm to Donald Trump's candidacy in 2016. Like many on the right, he suspected that the lifelong Democrat would be unreliable if he made it to the White House. But in this case, his own listeners were ahead of him. What finally turned Limbaugh around was the infamous "Flight 93" essay that Michael Anton wrote under a pseudonym in early September that year. Limbaugh devoted the bulk of one of his shows to reading the piece live on the air — and a good chunk of time two days later to dissecting my own take-down of the essay. By the end of those programs, it was clear that Rush had been converted. Trump was just the kind of brash, rude, vicious, fearless Republican that America and the conservative movement needed to finally turn back the tide of progressivism that, in the form of a looming Hillary Clinton victory, threatened to swamp the party and the country once and for all.

It is fitting that Anton's essay would prove to be so decisive in Limbaugh's shift of support to Trump — since in hindsight it represented the overturning of the old division of labor on the right once and for all. Instead of conservative intellectuals toiling with ideas while media personalities entertained the masses, now the intellectuals were making the case for their own irrelevancy, just as the GOP's institutional apparatus had given way to the populist onslaught during the primaries and party convention earlier that year. Instead of demagogues doing their dirty work while writers and thinkers aimed for something higher, now the writers and thinkers would take their cues from the demagogues, providing erudite justifications and excuses for whatever they did or said.

The interminable debate about the extent of Trump's control over this or that Republican politician will undoubtedly continue over the coming months and years. But in banding together to offer solemn tributes to Rush Limbaugh's life and influence, conservatives have shown us where they ultimately stand — with the man who, more than anyone else, helped transform the GOP into the party of Donald Trump.

Editor's note: A previous version of this article misidentified a 2012 GOP primary candidate. It has been corrected. We regret the error.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

Colbert, CBS spar over FCC and Talarico interview

Colbert, CBS spar over FCC and Talarico interviewSpeed Read The late night host said CBS pulled his interview with Democratic Texas state representative James Talarico over new FCC rules about political interviews

-

The Week contest: AI bellyaching

The Week contest: AI bellyachingPuzzles and Quizzes

-

Political cartoons for February 18

Political cartoons for February 18Cartoons Wednesday’s political cartoons include the DOW, human replacement, and more

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred