Winslow Homer: Force of Nature – an ‘eye-opening odyssey’ of an exhibition

National Gallery show aims ‘to enlarge Homer’s transatlantic reputation’ – and it deserves to succeed

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Few outside his native USA will be familiar with the artist Winslow Homer, said Waldemar Januszczak in The Sunday Times. Our national collection contains not a single “significant painting” of his, and if he is known at all on these shores, it is as a “boat painter” whose work is but a footnote in the story of 19th century art.

Yet in America, Homer (1836-1910) is a totemic figure – and, as this “compelling” exhibition at the National Gallery demonstrates, he is venerated for good reason. A largely self-taught artist, he was a singular painter with “a talent for storytelling” and a knack for injecting his canvases with an overwhelming drama that makes the work of his British contemporaries look fussy and affected by comparison.

The show brings together a stunning selection of his work, from the awe-inspiring seascapes for which he is best known, to paintings depicting the plight of freed slaves in the Bible Belt, to “everyday scenes” of 19th century American life. It gives us a picture of a pioneering artist with a refreshingly ambiguous outlook, a painter who “knew how to trigger interest and keep you guessing”. The aim of this “involving” display is “to enlarge Homer’s transatlantic reputation”, and it deserves to succeed.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Appeal of conflict and danger

Born into a “well-to-do New England family”, Homer established himself chronicling the Civil War as an illustrator-correspondent for Harper’s Weekly magazine, said Alastair Sooke in The Daily Telegraph. Clearly, conflict and danger appealed to him as subject matter: “he loved painting guns, shipwrecks, hunting scenes, freakish waves”. A transformative moment came during a stay in – of all places – a Northumbrian coastal village in 1881-82, when Homer found himself “transfixed by the elemental struggles of its fisherfolk”, and introduced a sense of “keening grandeur” to the maritime paintings he then favoured.

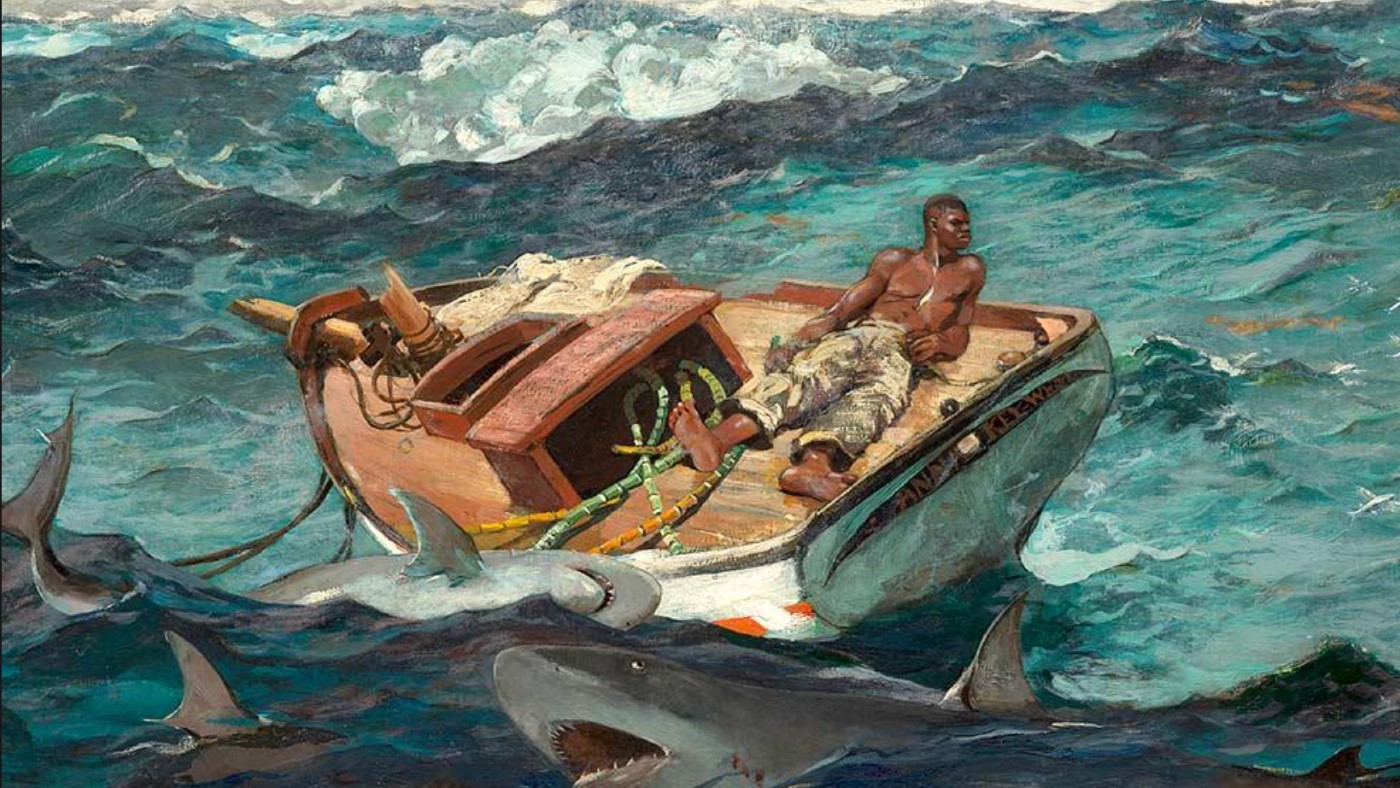

Perhaps the most famous of these is The Gulf Stream (1899), in which a “cartoonish, musclebound” black sailor clings to a boat with a broken mast, beset by swelling waves and some rather unconvincing sharks. “If this is a masterpiece, it’s a faintly ridiculous one.” The same could be said of much else here: the “downright peculiar” Undertow (1886), for instance, sees a group of semi-nude men, “as ripped as classical statuary”, rescuing women from the waves. We do see the odd “strong and memorable” painting here, but for the most part, it’s hard to get too excited about Homer. His work has “too much boyish, adventuresome melodrama, and insufficient mystery”.

Undeniably inconsistent work

“Homer can be a clumsy artist,” said Jonathan Jones in The Guardian. His work is undeniably inconsistent: he was “deeply chromatic and wild” one moment, “a bit dull” the next. Yet he has “an intensity and passion”, as well as a great eye for a resonant symbol.

His works that deal with the Civil War and the end of slavery are particularly arresting: Sharpshooter (1863), a painting developed from his war sketches, depicts a Union sniper aiming his rifle from a tree, his face “a blur”; A Visit from the Old Mistress (1876) sees an elderly white former slave-owner visiting a black family who once belonged to her. The family stare at their visitor “with much more in their eyes than can ever be said – a lifetime and more of questions and accusations”. For all of Homer’s limitations, this show is an “eye-opening odyssey”.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

National Gallery, London WC2. Until 8 January 2023

-

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problem

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problemThe Explainer Before her appointment as cabinet secretary, commentators said hostile briefings and vetting concerns were evidence of ‘sexist, misogynistic culture’ in No. 10

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy

-

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’Feature New insights into the Murdoch family’s turmoil and a renowned journalist’s time in pre-World War II Paris

-

6 exquisite homes with vast acreage

6 exquisite homes with vast acreageFeature Featuring an off-the-grid contemporary home in New Mexico and lakefront farmhouse in Massachusetts

-

Film reviews: ‘Wuthering Heights,’ ‘Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die,’ and ‘Sirat’

Film reviews: ‘Wuthering Heights,’ ‘Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die,’ and ‘Sirat’Feature An inconvenient love torments a would-be couple, a gonzo time traveler seeks to save humanity from AI, and a father’s desperate search goes deeply sideways

-

A thrilling foodie city in northern Japan

A thrilling foodie city in northern JapanThe Week Recommends The food scene here is ‘unspoilt’ and ‘fun’

-

Tourangelle-style pork with prunes recipe

Tourangelle-style pork with prunes recipeThe Week Recommends This traditional, rustic dish is a French classic

-

Samurai: a ‘blockbuster’ display of Japan’s legendary warriors

Samurai: a ‘blockbuster’ display of Japan’s legendary warriorsThe Week Recommends British Museum show offers a ‘scintillating journey’ through ‘a world of gore, power and artistic beauty’

-

BMW iX3: a ‘revolution’ for the German car brand

BMW iX3: a ‘revolution’ for the German car brandThe Week Recommends The electric SUV promises a ‘great balance between ride comfort and driving fun’