A Cold War tragedy: the execution of the Rosenbergs

Ethel and Julius Rosenberg were executed as Soviet spies in 1953, but was Ethel innocent?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

On 19 June 1953, Ethel and Julius Rosenberg were sent to the electric chair for being Soviet spies. Sixty-eight years later, their sons are still trying to clear their mother’s name. Hadley Freeman reports

“It was a queer, sultry summer, the summer they electrocuted the Rosenbergs…” So begins Sylvia Plath’s 1963 novel The Bell Jar, referring to the Jewish American couple, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, convicted of conspiracy to commit espionage and sent to the electric chair on 19 June 1953. Their execution is seen by many as America’s Cold War nadir. The Rosenbergs are still the only Americans ever put to death in peacetime for espionage, and Ethel is the only American woman killed by the US government for a crime other than murder.

During their trial, Ethel in particular was vilified for prioritising communism over her children, and the prosecution insisted she was the dominant half of the couple, because she was three years older. But questions about whether she was guilty at all have grown louder in recent years, and a new biography presents her in a different light.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

“Ethel was killed for being a wife. She was guilty of supporting her husband,” Anne Sebba, author of Ethel Rosenberg: A Cold War Tragedy, tells me. And for that, the 37-year-old mother of two had five massive jolts of electricity pumped through her body. Eyewitnesses said smoke rose from her head.

The killing of the Rosenbergs was so shocking it became part of popular culture, referenced in works by Tony Kushner and Woody Allen. The most moving cultural response was E.L. Doctorow’s 1971 novel, The Book of Daniel, which imagines the life of the Rosenbergs’ oldest child, whom he renames Daniel. In reality, the older Rosenberg child is called Michael, and his younger brother is Robert.

It is a bitter, rainy spring day, the day I interview the Rosenbergs’ sons. Three and seven when their parents were arrested, six and ten when they were killed, they are now known as Michael and Robert Meeropol, having taken the surname of the couple who eventually adopted them. When their parents were arrested, Michael, a challenging child, acted up even more, whereas Robert withdrew into himself. This dynamic still holds true: “Robert is more reserved and I fly off the handle,” says Michael, 78, a retired economics professor.

Patient, methodical Robert, 74, a former lawyer, considers every word carefully. We are talking by video: Robert is in Massachusetts, Michael in New York state. The differences between them are obvious, but so is their closeness: since Michael’s wife, Ann, died two years ago, his brother has called him daily. “Rob and I are unusual siblings. We have dealt with so many struggles, we are very enmeshed,” says Michael.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The brothers’ struggles began on 17 July 1950, when their father, Julius, was arrested at their New York home on suspicion of espionage. Ethel’s brother, David Greenglass, had earlier been arrested for the same crime. Significantly, the Korean War – seen by the US as a life-or-death struggle with communism – had just begun. Senator Joseph McCarthy was warning about “homegrown commies”, and the US entered a red panic. A month later, Ethel too was arrested. She called Michael at home and told him that she had also been arrested. “So you can’t come home?” he asked. “No,” she replied. The seven-year-old screamed.

Julius and Ethel, like David Greenglass and his wife, Ruth, were communists. Like many Jews, they became interested in the movement in the 1930s when it seemed a way to fight fascism. Unlike many others, they stuck with it after the Soviet Union and Germany signed a non-aggression pact, ostensibly becoming allies. “These were people who grew up during the Depression,” says Sebba. “They thought they were making the world a better place.” David worked as a machinist at the Los Alamos atomic weapons laboratory. He was arrested after being identified as part of a chain passing atomic secrets to the Soviets. David admitted his guilt, and his lawyer advised the best thing he could do for himself, and to give his wife immunity, would be to turn in someone else. Then the Rosenbergs were arrested.

The FBI believed Julius was a kingpin who recruited Americans as spies and used David to pass on atomic secrets to the Russians. The initial allegations against Ethel were that she “had a discussion with Julius Rosenberg and others in November 1944”, and “had a discussion with Julius Rosenberg, David Greenglass and others in January 1945” – in other words, she talked to her husband and brother. It was feeble stuff, as the FBI knew. At first, David testified that his sister had not been involved. However, his wife said that Ethel had typed up information that David had given Julius to pass to the Soviets. David changed his story before the trial to corroborate his wife’s version, probably under pressure from Roy Cohn, the ambitious chief assistant prosecutor. This was the key evidence against Ethel – but even with that, Myles Lane, the chief assistant attorney for New York’s Southern District, admitted privately: “The case is not strong against Mrs Rosenberg. But [to act] as a deterrent, I think it is very important that she be convicted, too.” FBI director J. Edgar Hoover agreed.

At the trial, David testified that he gave Julius details of the atomic bomb, and that Ethel was involved in their discussions. Because he gave names, David ended up serving nine years. Ruth was free to stay home with the children. The Rosenbergs, who pleaded innocent, were found guilty. Judge Irving Kaufman carefully considered their sentence. Hoover, aware of how it would look if the US executed a young mother, urged against the death sentence for Ethel, but Cohn argued for it and won.

Michael and Robert never saw the Greenglasses again after the trial, and all Michael remembers of them is: “David looked like a nondescript schlub and Ruth was a cold fish. But is that true, or just a nephew who wants to expose the people who lied about my parents?” he asks. Ethel herself has long been portrayed as cold. In reality, Sebba says, she was a devoted mother who consulted a child therapist to improve her parenting skills. But when she was arrested, all the aspirations she had of giving her boys a happy childhood imploded. At first the boys lived with her mother, Tessie, who resented the situation. Worse still, they were later put in a children’s home. Eventually, Julius’s mother, Sophie, took them in, but the boys were too much for their frail grandmother. None of their aunts or uncles would take them, so they were shipped around to various families.

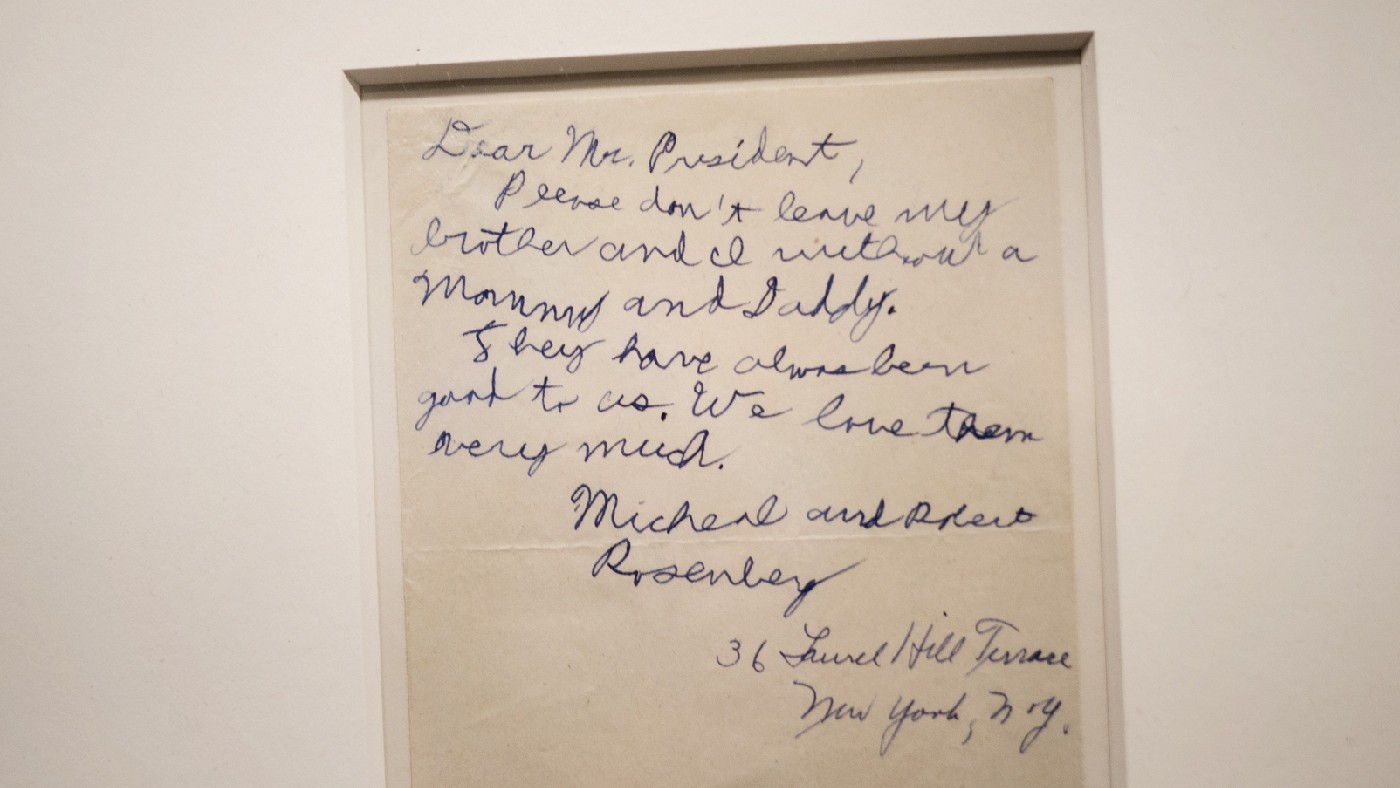

For the boys’ sake, Ethel always maintained a happy front. “We always had a good time on prison visits: singing, talking, enjoying ourselves,” says Michael. He even used to play hangman with his father, although he didn’t realise the irony until he was an adult. The US government said that if Julius gave them names of other spies, and he and Ethel confessed, their lives would be spared. The Rosenbergs issued a statement: “By asking us to repudiate the truth of our innocence, the government admits its own doubts concerning our guilt… we will not be coerced, even under pain of death, to bear false witness.” On 16 June 1953, the children were brought to New York’s Sing Sing prison to say goodbye to their parents. On 19 June, Ethel and Julius wrote their last letter to their children: “Always remember that we were innocent and could not wrong our conscience. We press you close and kiss you with all our strength. Lovingly, Daddy and Mommy.” Just after 8pm, the Rosenbergs were executed.

The boys were eventually adopted by Abel and Anne Meeropol, an older left-wing couple. They grew up in anonymity among loving people. Abel was a songwriter, whose biggest hit was Strange Fruit; the boys were raised on the royalties from the most famous song of the civil rights era. “Living with Abel and Anne, it felt like we won the lottery,” says Michael. The boys enjoyed a happy upbringing, telling almost no one their real surname – until they were unmasked by the local media in 1973. They used the exposure to campaign for their parents, writing a memoir and suing the FBI and CIA for the release of documents which they believed proved their parents’ innocence.

In 1995, however, the Venona papers were declassified. These were secret Soviet messages intercepted by US counterintelligence. The Rosenbergs were named. Julius, it was now clear, had definitely been spying for the Soviets, codenamed him “Antenna” and later “Liberal”. David and Ruth Greenglass were also spies. But there was little about Ethel. She didn’t have a codename. She was, the cables noted, “a devoted person” (i.e. a communist) but “[she] does not work” (i.e. she was not a spy). “That transcript was as close to a smoking gun as we would get,” says Robert, “because it said Julius and Ethel didn’t do the thing they were killed for. Ethel didn’t work and Julius wasn’t an atomic spy, he was a military-industrial spy” – i.e. he hadn’t passed on details about the atomic bomb.

Michael was more sceptical of the Venona papers, wondering if they were “CIA disinformation”. But in 2008 he finally accepted them when Morton Sobell – who was convicted along with the Rosenbergs – publicly confirmed that Julius had not helped the Russians build the bomb. “What he gave them was junk,” Sobell said. Of Ethel, Sobell said, “What was she guilty of? Of being Julius’s wife.” In 1996, David Greenglass finally admitted he had lied about his sister: “I told them the story and left her out of it, right? But my wife put her in it. So what am I gonna do, call my wife a liar?” He added, “I frankly think my wife did the typing, but I don’t remember.” Ruth died in 2008, David in 2014.

Robert launched the campaign for Ethel’s exoneration in 2015. Yet her innocence raises more questions than it settles. Given she was a true believer in communism, why didn’t she join Julius in spying? “Her main identity was as a wife and a mother,” says Sebba, “and that’s what mattered to her.” So why didn’t Julius save Ethel? He could easily have given names to save her life. “Dad’s unwillingness to rat out his fellows [was] personal,” says Michael. “These were his friends!” Until the end, Julius believed they wouldn’t go to the chair. The government hoped that, too – but they wanted names. After Ethel was killed, the deputy attorney general William Rogers said, “She called our bluff.”

The defining mystery about Ethel is why she chose to stay silent. Her letters show that she was deeply in love with her husband, but also full of anxiety about the boys. “Ethel thought life without Julius would have been valueless,” says Sebba. “Because her sons would never have respected her, because she would have had to name names.” Their childhoods would have been easier “if Julius had cooperated”, says Robert. “He’d have been in prison and Ethel would have been released” – as with the Greenglasses. “But as an adult I would much rather be the child of Ethel and Julius than the child of David and Ruth Greenglass.”

Michael and Robert’s campaign for their mother’s exoneration was struck a blow with the election of Donald Trump, whose original mentor was none other than Roy Cohn. Robert says there was no point in asking Trump for help. But now the campaign is starting again, and they are “optimistic” President Biden will look at it favourably. I ask why it matters now. Why not leave this in the past? “It’s personal as well as political,” says Robert, emphasising both words. “That the US government invented evidence to obtain an execution is a threat to every person in this country.”

The biggest question about Ethel for me relates to her sons. Following our interview, I end up speaking to them several more times, partly because they are so delightful to talk to: intelligent, interesting, admirable. How did they triumph over such trauma? Sebba tells me she asked the same thing of Elizabeth Phillips, the child therapist consulted by Ethel before her arrest. “She told me it was down to three things,” Sebba says. “She said, ‘One, they have a high level of intelligence. Two, they had amazing adoptive parents. But we now know how important those early years of life are, and Ethel must have given those two boys so much in those years that it lasted all their lives. Ethel must have been an extremely good mother.’”

A longer version of this article appeared in The Guardian. © Guardian News and Media Ltd