A history of book banning in America

PEN America says free expression is under threat. It's not the first time.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Books are disappearing from the shelves of America's schools. Books about gay and lesbian characters. Books about Black and Latino people, and books about Jewish and Muslim people. Books that are fiction and books that are non-fiction — even books of poetry. All gone.

The country faced an "unprecedented flood" of book banning in schools during the 2021-2022 school year, PEN America reported this week, driven by activist groups and conservative state legislatures that have passed laws cracking down on "critical race theory" and the discussion of sexuality and gender identity in classrooms. The organization found 2,532 instances of book ban attempts, affecting 1,648 book titles. The trend poses "a dangerous precedent to those in and out of schools," the organization said, because the bans threaten "the future of American democracy, public education, and free expression."

But the current backlash against some books and ideas isn't the first time this has happened in American history. We've seen this story before — some observers say that attempts to censor and block controversial books go back almost to the earliest days of European settlement in America, when Thomas Morton's book attacking Puritans was banned, naturally, by the Puritans. Often, the issues of race, sex, or religion are involved. Here are some other examples:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"Uncle Tom's Cabin," by Harriet Beecher Stowe

This is "perhaps the most infamous and consequential banned book of all time," the First Amendment Museum says in its overview on the topic. Published in 1852 — just under a decade before the outbreak of the Civil War — Uncle Tom's Cabin was unabashed in its depiction of slavery as an evil, brutal institution. It succeeded in arousing the ire of much of the American public, but Stowe's book "obviously ruffled quite a few feathers" in Southern states where enslavers held most of the region's culture, economic, and political power. Some communities prohibited the book outright, but cultural pressure was also brought to bear: One bookseller in Mobile, Alabama, was reportedly forced to leave town after selling the novel.

"Many historians point to Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin as the first book in the United States to experience a ban on a national scale," Amy Brady wrote in 2016 for LitHub. The novel wasn't just controversial in America: It was also reputedly banned in Czarist Russia, which was in the process of ending its own system of serfdom. But what was once considered an important, crusading novel has come to be seen as racist and patronizing in its depiction of Black people.

The Comstock Act

This law might be the Babe Ruth of American censorship — the all-time champion. In 1873, Congress passed the measure, formally known as the "Act for the Suppression of Trade in, and Circulation of, Obscene Literature and Articles of Immoral Use." Those "articles" included contraception and abortions, and in practice, they also included pretty much any book that contained discussion or depictions of sex, no matter how artistic or anodyne: The law didn't have a specific definition of "obscenity," so officials cast a wide net.

The Comstock Act "led to the banning of classics such as Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales, Boccaccio's The Decameron, and, later, to persecute modern authors like Ernest Hemingway, John Steinbeck, William Faulkner, and F. Scott Fitzgerald," Granta said in a 2017 celebration of banned books. Other writers were even arrested under the act, including Ezra Heywood, who wrote a book arguing that women should have control over their bodies, and Margaret Sanger, who was then writing a sex education column for a socialist newspaper.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"Banned in Boston"

In the early 20th century, the New England Watch and Ward Society was the terror of publishers everywhere. The society "crusaded against vice in all its forms, aiming to keep Boston free from bawdy burlesque shows, prostitution, and poker games," Edgar B. Herwick III wrote for WGBH in 2016. Books especially were subject to a sort of censorship. The group's leaders "had a secret gentleman's agreement with the booksellers in Boston, to ban objectionable books from their City on a Hill." So classics like Voltaire's Candide and Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass were difficult — at best — to obtain, and "Banned in Boston" became both a rallying cry and a selling point for some novels.

Then in 1926, famed editor H.L. Mencken purposely got himself arrested for selling copies of his magazine, American Mercury, which contained a short story about a prostitute. Mencken — who would later declare Boston a city of "frenzied moralists" — beat the rap: He was acquitted on all the charges. He was an exception, Mass Humanities notes in a history of the era: "Boston continued to lead the nation in the banning of books for another 30 years."

The comic book scare

"Some 60 years ago, during the era of McCarthyism, comic books became a threat, causing a panic that culminated in a Senate hearing in 1954," Alex Abad-Santos wrote for Vox in 2015.

Wait. Comic books?

Yes. In the years after World War II, some comics publishers "dipped into gore and horror" and featured "graphic" crime stories. That drew the attention of a psychiatrist named Fredric Wertham, who became famous for his crusade against comic books as a major cause of juvenile delinquency. "Formerly to impair the morals [of] a minor was a punishable offense," he testified in the Senate hearing. "It has now become a mass industry."

Under the threat of regulation, comics publishers established the Comics Code Authority, which quickly put the clamps on offending titles. "Almost overnight, comics were brought down to a level appropriate only for the youngest or dimmest of readers," the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund says in its history. "Horror, Crime, Science Fiction and other genres appealing to older and more sophisticated readers were wiped out for a generation."

These days, of course, comics-inspired movies and TV shows dominate the box office and our attention. It just goes to show — today's banned books might be tomorrow's mass culture.

Joel Mathis is a writer with 30 years of newspaper and online journalism experience. His work also regularly appears in National Geographic and The Kansas City Star. His awards include best online commentary at the Online News Association and (twice) at the City and Regional Magazine Association.

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy

-

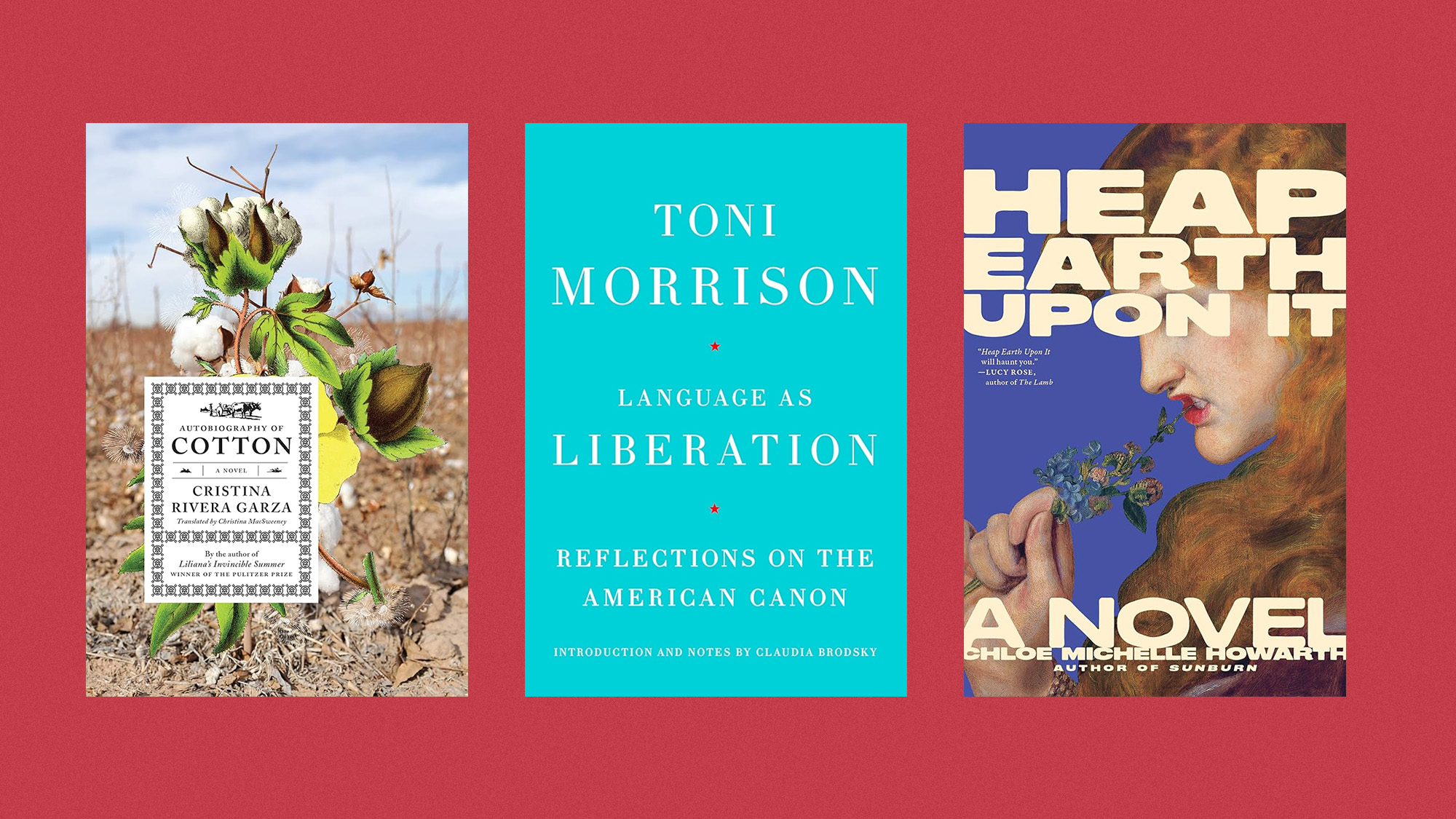

February’s books feature new Toni Morrison, a sapphic love tale and a criticism of Mexican history

February’s books feature new Toni Morrison, a sapphic love tale and a criticism of Mexican historyThe Week Recommends This month’s new releases include ‘Autobiography of Cotton’ by Cristina Rivera Garza, ‘Language as Liberation’ by Toni Morrison and ‘Heap Earth Upon It’ by Chloe Michelle Howarth

-

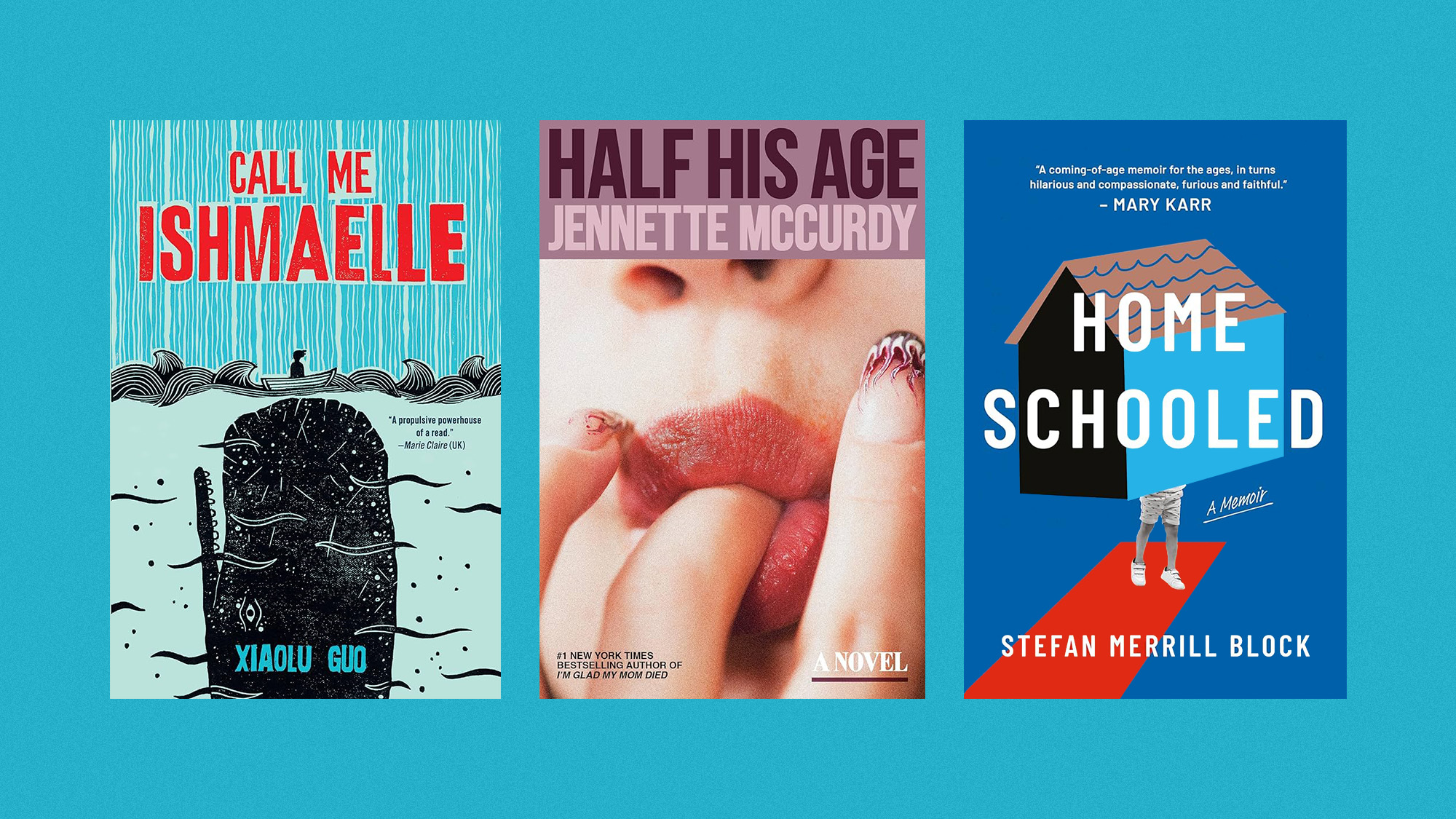

January’s books feature a revisioned classic, a homeschooler’s memoir and a provocative thriller dramedy

January’s books feature a revisioned classic, a homeschooler’s memoir and a provocative thriller dramedyThe Week Recommends This month’s new releases include ‘Call Me Ishmaelle’ by Xiaolu Guo, ‘Homeschooled: A Memoir’ by Stefan Merrill Block, ‘Anatomy of an Alibi’ by Ashley Elston and ‘Half His Age’ by Jennette McCurdy

-

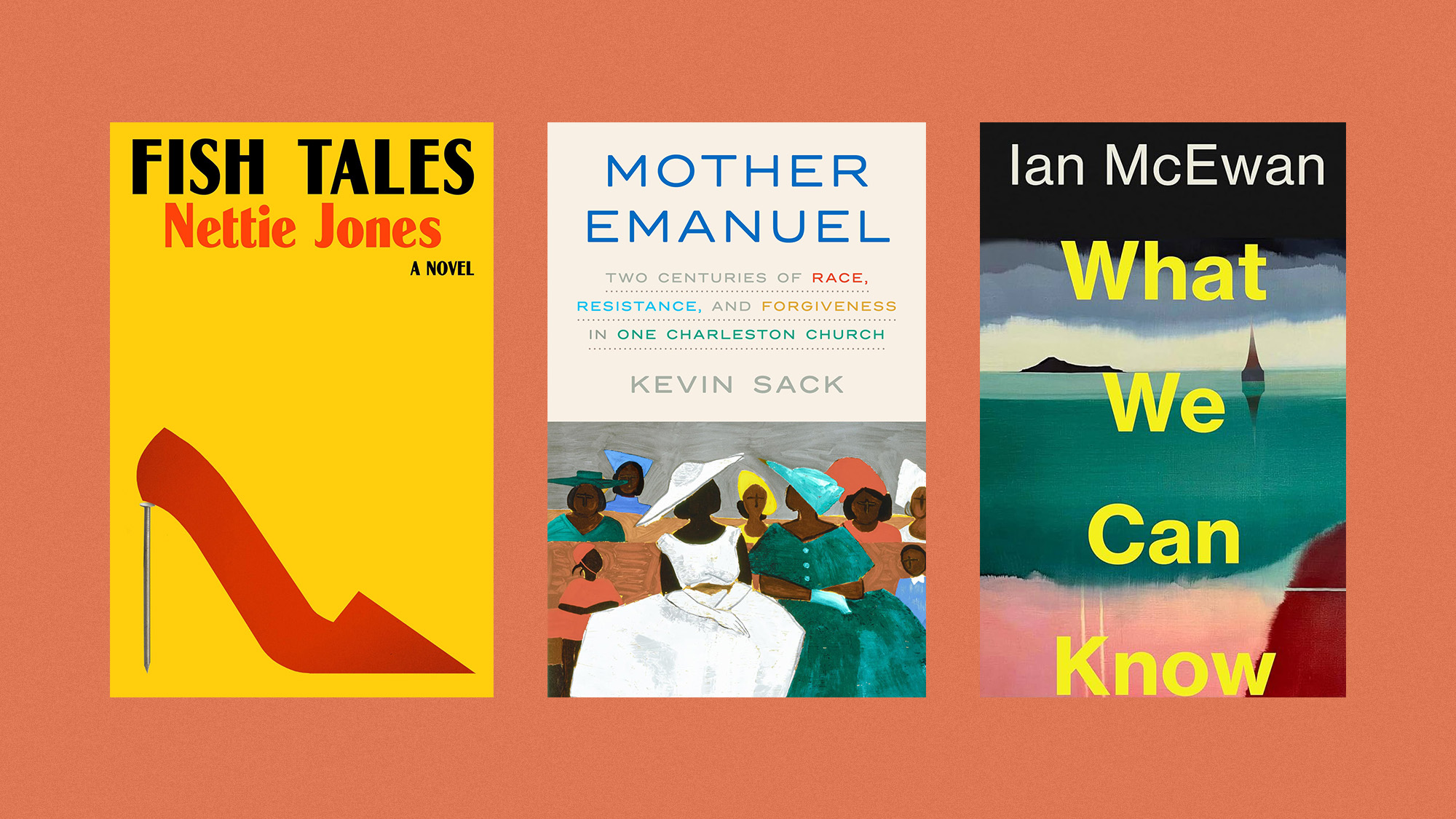

The best books of 2025

The best books of 2025The Week Recommends A deep dive into the site of a mass shooting, a new release from the author of ‘Atonement’ and more

-

One great cookbook: Natasha Pickowicz’s ‘More Than Cake’

One great cookbook: Natasha Pickowicz’s ‘More Than Cake’the week recommends The power of pastry brought to inspired life

-

December’s books feature otherworldly tales, a literary icon’s life story and an adult royal romp

December’s books feature otherworldly tales, a literary icon’s life story and an adult royal rompThe Week Recommends This month's new releases include ‘The Heir Apparent’ by Rebecca Armitage and ‘Tailored Realities’ by Brandon Sanderson

-

Margaret Atwood’s memoir, intergenerational trauma and the fight to make spousal rape a crime: Welcome to November books

Margaret Atwood’s memoir, intergenerational trauma and the fight to make spousal rape a crime: Welcome to November booksThe Week Recommends This month's new releases include ‘Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts’ by Margaret Atwood, ‘Cursed Daughters’ by Oyinkan Braithwaite and 'Without Consent' by Sarah Weinman

-

One great cookbook: Niloufer Ichaporia King’s ‘My Bombay Kitchen’

One great cookbook: Niloufer Ichaporia King’s ‘My Bombay Kitchen’The Week Recommends A personal, scholarly wander through a singular cuisine

-

One great cookbook: Camilla Wynne's 'Jam Bake'

One great cookbook: Camilla Wynne's 'Jam Bake'The Week Recommends A guide to pristine jam-making, plus the baked goods that love them