Climate, crime, and the bodies at Lake Mead

What do the mafia and global warming have to do with each other?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

They keep finding dead people at Lake Mead.

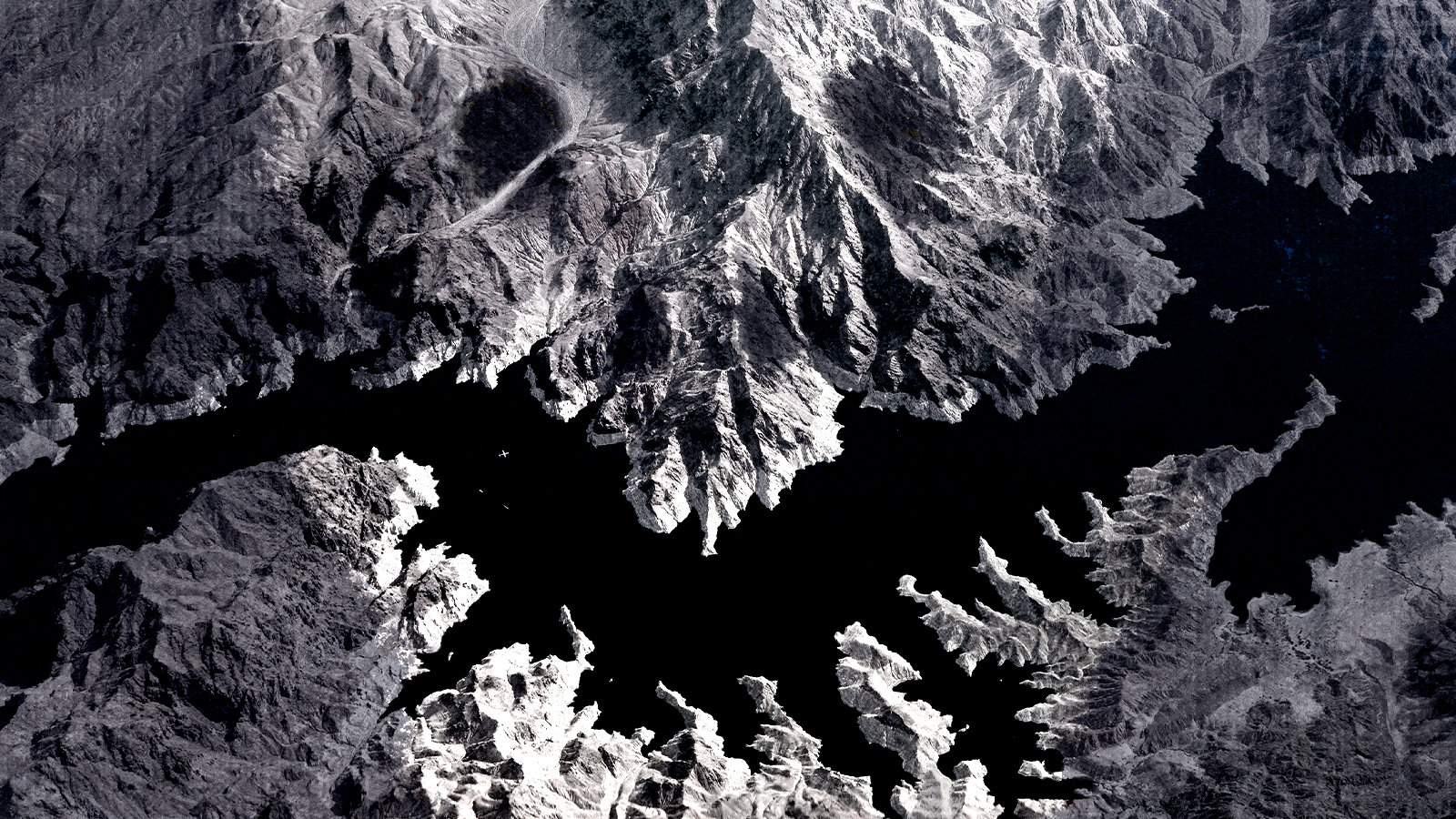

It happened again this week: "Human skeletal remains" were discovered at the lake, which is located 20 miles east of Las Vegas. That's the fourth time a body has been found in recent months — starting in May, when boaters discovered a body found in a barrel exposed by low water levels. Another body, discovered in July, might be that of a 56-year-old man who died in 2004 saving his wife after a boating accident. The gruesome trend even inspired a lawyer to put up a billboard telling Las Vegas residents to "demand compensation!" if they're injured looking for bodies at the lake. (He says it was a joke.)

It's not just human remains that are being found. "Water levels have plummeted so much that, in addition to several bodies, they have exposed a sunken World War II-era vessel," CNN reports. Why are the water levels dropping? Why are so many bodies being discovered? What's going on at Lake Mead? Here's everything you need to know:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Why is the water falling at Lake Mead, anyway?

Climate change, of course. The western regions of the United States are in the midst of a decades-long "megadrought" that is drying up water sources used by millions of people. Lake Mead, which is fed by the Colorado River and three smaller tributaries, is not exempt from the damage. "The low water level comes at [a] time when 74 percent of nine western states face some level of drought; 35 percent of the area is in extreme or exceptional drought," NASA's Earth Observatory noted last month. That's taking a huge toll on water supplies: "Continuing a 22-year downward trend, water levels in Lake Mead stand at their lowest since April 1937, when the reservoir was still being filled for the first time."

In other words, there's a lot of water that's not there anymore. "In Lake Mead alone, the net water loss has worked out to more than 6 trillion gallons," Zack Budryk writes for The Hill. That means a lot of stuff that used to be underwater is no longer underwater — thus all the stories about newly discovered bodies — but there will also be more profound effects: "Hoover Dam is already seeing reduced electricity production from Lake Mead's shrinking size" and the region's drinking water is threatened by the drought. So the human remains, while notable, are just a symptom of a much larger crisis.

Is the mafia responsible for all these bodies?

The proximity of Lake Mead to Las Vegas — and that city's, er, colorful associations with organized crime — has not gone unnoticed. And it is certainly the case that some of the newly discovered bodies appear to be the victims of foul play. The body that was found in a barrel had suffered a gunshot wound, for example, and appears to be somebody who died sometime between the 1970s and the 1980s. An obvious point: "Anytime you have a body in a barrel, clearly there was somebody else involved," one investigator told CNN. One woman told TV station KVVU that she believed the victim was her brother, who went missing in 1977 and was connected to mobsters.

But it is also true that Lake Mead is huge — it spans the Arizona-Nevada border, 65 miles long and more than nine miles wide at its widest point. That means there have been plenty of opportunities over the years for unfortunate boaters and swimmers to get into trouble that they couldn't get out of. There was the aforementioned 2004 incident, for example, and another body found in July was of a woman who disappeared while riding a personal watercraft.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Some people can't help but play up the crime angle, though. "There's no telling what we'll find in Lake Mead," former Las Vegas Mayor Oscar Goodman told CBS News. "It's not a bad place to dump a body."

So what's next?

Lake Mead — and the 25 million people who depend on it for water and power — faces a great deal of uncertainty. A February study in Nature Climate Change says the western drought could last through 2030, meaning the dry conditions across the West could continue to last for nearly a decade or more. Lake Mead may reach a crisis point long before that: The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation forecasts water levels to hit a record low in November 2023, Joanna Allhands reported in May for the Arizona Republic: "It's dangerously low territory."

The lake supplies water for three states, some Native American tribes, and Mexico, Daniel Rothberg points out in the Las Vegas Independent. That makes the current drought increasingly scary: "A future in which Lake Mead declines so much that water could no longer pass through Hoover Dam would mark a large-scale crisis for the entire Southwest." The federal government announced in June that it will cut back on water deliveries to those customers in order to protect and preserve the overall system. "The message is, get ready for a drier future," said one NASA scientist. Lake Mead is gradually revealing some dark secrets of the region's past, but it is the future that we need to be concerned about.

Joel Mathis is a writer with 30 years of newspaper and online journalism experience. His work also regularly appears in National Geographic and The Kansas City Star. His awards include best online commentary at the Online News Association and (twice) at the City and Regional Magazine Association.