The risky reality of 'breakthrough' COVID infections

Delta is different

A popular British news broadcaster named Andrew Marr appeared on BBC News at the end of June to share he'd recently contracted a "nasty" case of COVID-19. "It was really, really quite unpleasant," the 61-year-old Marr said, adding that he had "a high temperature, muscle ache, the shakes, a bad headache, and flu-like cold symptoms."

That all sounds pretty textbook as far as COVID-19 stories go, but with one catch: Marr was fully vaccinated. He'd received two doses of the Pfizer vaccine back in the spring, and, by his own account, felt "if not king of the world, at least almost entirely immune." He was not.

In the weeks since, I've noticed similar anecdotes cropping up. "Friend messages to tell me has COVID after 2nd vaccine," someone tweeted. "Several people I know have been (badly) infected with Delta after being fully vaccinated," wrote British journalist Kathryn Bromwich. Many of the anecdotes are coming from the United Kingdom, where I live. Here, the Delta variant of the virus is dominant and case rates are soaring despite half the adult population being fully vaccinated. But they're also trickling out of the U.S. American author John Pavlovitz shared how his family contracted the virus despite most of them having received two doses. "I was fully vaccinated and right now (as my father used to say) I feel like a sh*t sandwich without the bread," he said.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Anecdotes, of course, are not scientific data. They should not be relied upon to inform policy. But they are often canaries in the coal mine, early indicators of emerging trends soon to be reflected in the numbers. And in the coming weeks and months, as cases rise again and the Delta variant spreads among highly-vaccinated populations, we will be hearing more about post-vaccination infections. They may even prove more common than we had anticipated. Policymakers should be sounding the alarm about this now — not to dampen enthusiasm about the incredible vaccines on offer, but to encourage caution as the virus continues to rage, mutate, and adapt. The pandemic isn't over, and acting like it is will only prolong it further.

So-called "breakthrough infections" — when someone tests positive for a virus despite being fully vaccinated against it — have always been a reality. No vaccine is perfect. And it's a sheer statistical fact that the more people we vaccinate, the share of new infections that happen to be among vaccinated people will rise. But you could be forgiven for believing the COVID vaccines were foolproof. The scientific community was positively jubilant when the trial data about the vaccines first emerged. Ninety-five percent efficacy for a vaccine aimed at curbing an unpredictable illness that brought the entire world to a standstill and killed millions? It seemed like a miracle. "These are game changers," Dr. Gregory Poland, a vaccine researcher at the Mayo Clinic, told The New York Times last December. "We were all expecting 50 to 70 percent." For context, the flu vaccine is only 60 percent effective, and that's in a good year.

Indeed, the COVID vaccines approved in the U.S. are incredibly effective, especially against severe illness, hospitalization, and death. But most of the efficacy data we have relied upon so far relates to the earlier strains of COVID. Now, the Delta variant is changing the game. Andy Slavitt, a former senior adviser to President Biden's COVID Response Team, called it COVID "on steroids." It's between 40 and 60 percent more infectious than the strain that came before it, and appears to have some level of vaccine escape: A single shot in a two-dose regimen is less protective against Delta. Meanwhile, various emerging studies put the Pfizer vaccine's effectiveness at preventing symptomatic disease from the Delta variant somewhere between 80 and 90 percent — down from 95 percent. A controversial report out of Israel put the vaccine's protection against all disease — symptomatic or not — much lower, at 64 percent.

To be clear, these numbers are still good! You should still get the vaccine, and be confident that doing so will protect you from landing in the hospital on a ventilator. But what's concerning is the way many seem to be dismissing incremental drops in vaccine effectiveness as nothing to be alarmed about. "If you're vaccinated, I wouldn't worry," Dr. Ashish Jha, dean of Brown University's School of Public Health, told CNN. It's true that all the data suggest the Pfizer vaccine still protects against severe illness, so if staying out of the hospital is all you care about, then sure, as Jha says, there's little reason to worry. But it's important to remember that even mild cases of COVID can be pretty awful, not to mention that they're contagious and could sicken other people.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Telling fully vaccinated people not to worry about breakthrough infections is reminiscent of harmful early-pandemic attempts to downplay the threat of the virus, and it perpetuates the already flawed idea that they are, as Marr put it, "almost entirely immune." And that's just not true. The reality is, we may not know the rate of breakthrough infections caused by Delta in the U.S. until it's too late. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention put the number at 4,115 as of June 21 — but that's just a measure of people who were hospitalized or died. The true number of breakthrough infections is likely much higher, because the CDC stopped counting "mild" or "moderate" cases back in May, a decision that proved controversial with some scientists. "Just looking at hospitalizations or cases from people who die is really keeping, I believe, blindfolds on your eyes and not fully understanding what's happening with this virus," Rick Bright, a former federal health official, now with the Rockefeller Foundation, told NPR. "It puts us at a disadvantage of better understanding this virus and how to end the pandemic."

Believing oneself invincible encourages risky behavior — going unmasked in crowded spaces, for example, or ignoring symptoms — and coddles one into a false sense of security. We do not know to what extent fully vaccinated individuals can spread the Delta variant to others. We do not know yet if they can become long-haulers. We do not know yet if Delta will mutate into something more contagious, more deadly, or even more vaccine resistant. But with every new infection — breakthrough or otherwise — the chances of new variants emerging increase. And who knows, one of them could threaten your vaccination status. As Ravindra Gupta, a clinical microbiologist at the University of Cambridge, told Ed Yong at The Atlantic, reduction in the vaccines' effectiveness will be incremental. "I don't think there'll suddenly be a variant that pops up and evades everything, and suddenly our vaccines are useless," Gupta said, adding: "With every stepwise change in the virus, a chunk of protection is lost in individuals."

On a humanitarian scale, downplaying breakthrough infections gives vaccinated people an excuse to ignore those who cannot or will not get the shot. It engenders an individualistic, look-the-other-way mentality: Why should I care about COVID anymore? I'm not going to get sick. Time to move on. In fact, COVID remains everyone's problem. Just half the adult population in America is fully vaccinated, and cases have stopped declining. This puts everyone at risk. The longer the virus is allowed to circulate, and the more unvaccinated people there are, the greater the risk of breakthrough infections. Bringing the virus to heel should be a priority for all of us.

Part of the challenge comes down to pure linguistics. When we talk about breakthrough infections, they're often labeled as "rare." But what does that even mean, anyway? Does it mean exceedingly unlikely? Less than 1 percent chance? One in a thousand? If it simply means "less likely," then in the case of breakthrough infections, it's accurate. But many of us are so desperate to put the pandemic behind us (and reasonably so!) that we see "rare" and interpret it as "impossible." We take off the mask. We breathe a sigh of relief. We let our guard down. And before we know it, we're sick. Our families are sick.

Some agencies are sounding the alarm about breakthrough infections. The World Health Organization, for example, now recommends that even vaccinated individuals continue to mask up as Delta spreads. But the CDC says the fully-vaxxed don't need masks because they're "safe." In the U.K. the government is forging ahead with lifting almost all restrictions. But what we need now, in the face of Delta, is a return to the so-called "swiss cheese" model of prevention, in which we employ numerous layers of protection — like contact tracing, masking, limiting our time in large groups, ventilation, and yes, vaccines — to keep the virus under control.

We don't know just how many breakthrough infections will come from the Delta variant. The U.K. will be a good indicator over the coming weeks and months. But regardless, it's important to remember that vaccines are not a silver bullet. That is not to say they are useless — far from it. They truly are miraculous, and you should absolutely get the shot. Pavlovitz, the author I mentioned earlier, said he shudders "to think how bad it might have been had we not been vaccinated." But we should not allow the vaccine to lull us into complacency. The virus is still evolving, and so must we.

Jessica Hullinger is a writer and former deputy editor of The Week Digital. Originally from the American Midwest, she completed a degree in journalism at Indiana University Bloomington before relocating to New York City, where she pursued a career in media. After joining The Week as an intern in 2010, she served as the title’s audience development manager, senior editor and deputy editor, as well as a regular guest on “The Week Unwrapped” podcast. Her writing has featured in other publications including Popular Science, Fast Company, Fortune, and Self magazine, and she loves covering science and climate-related issues.

-

Wellness retreats to reset your gut health

Wellness retreats to reset your gut healthThe Week Recommends These swanky spots claim to help reset your gut microbiome through specially tailored nutrition plans and treatments

-

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’Under the radar The gender gap has hit the animal kingdom

-

7 hotels known for impeccable service

7 hotels known for impeccable serviceThe Week Recommends Your wish is their command

-

Covid-19 mRNA vaccines could help fight cancer

Covid-19 mRNA vaccines could help fight cancerUnder the radar They boost the immune system

-

The new Stratus Covid strain – and why it’s on the rise

The new Stratus Covid strain – and why it’s on the riseThe Explainer ‘No evidence’ new variant is more dangerous or that vaccines won’t work against it, say UK health experts

-

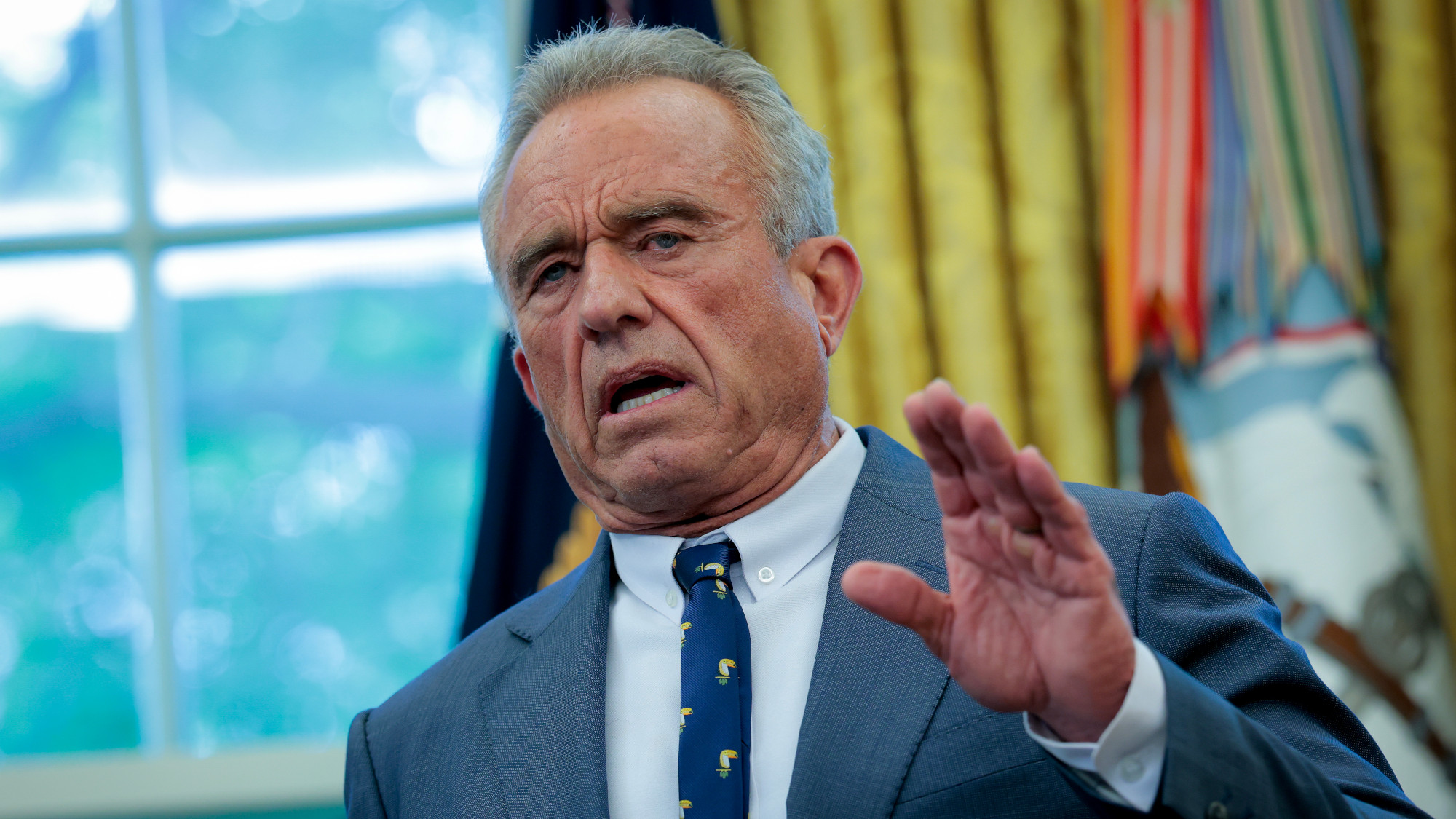

RFK Jr. vaccine panel advises restricting MMRV shot

RFK Jr. vaccine panel advises restricting MMRV shotSpeed Read The committee voted to restrict access to a childhood vaccine against chickenpox

-

RFK Jr. scraps Covid shots for pregnant women, kids

RFK Jr. scraps Covid shots for pregnant women, kidsSpeed Read The Health Secretary announced a policy change without informing CDC officials

-

New FDA chiefs limit Covid-19 shots to elderly, sick

New FDA chiefs limit Covid-19 shots to elderly, sickspeed read The FDA set stricter approval standards for booster shots

-

RFK Jr.: A new plan for sabotaging vaccines

RFK Jr.: A new plan for sabotaging vaccinesFeature The Health Secretary announced changes to vaccine testing and asks Americans to 'do your own research'

-

Five years on: How Covid changed everything

Five years on: How Covid changed everythingFeature We seem to have collectively forgotten Covid’s horrors, but they have completely reshaped politics

-

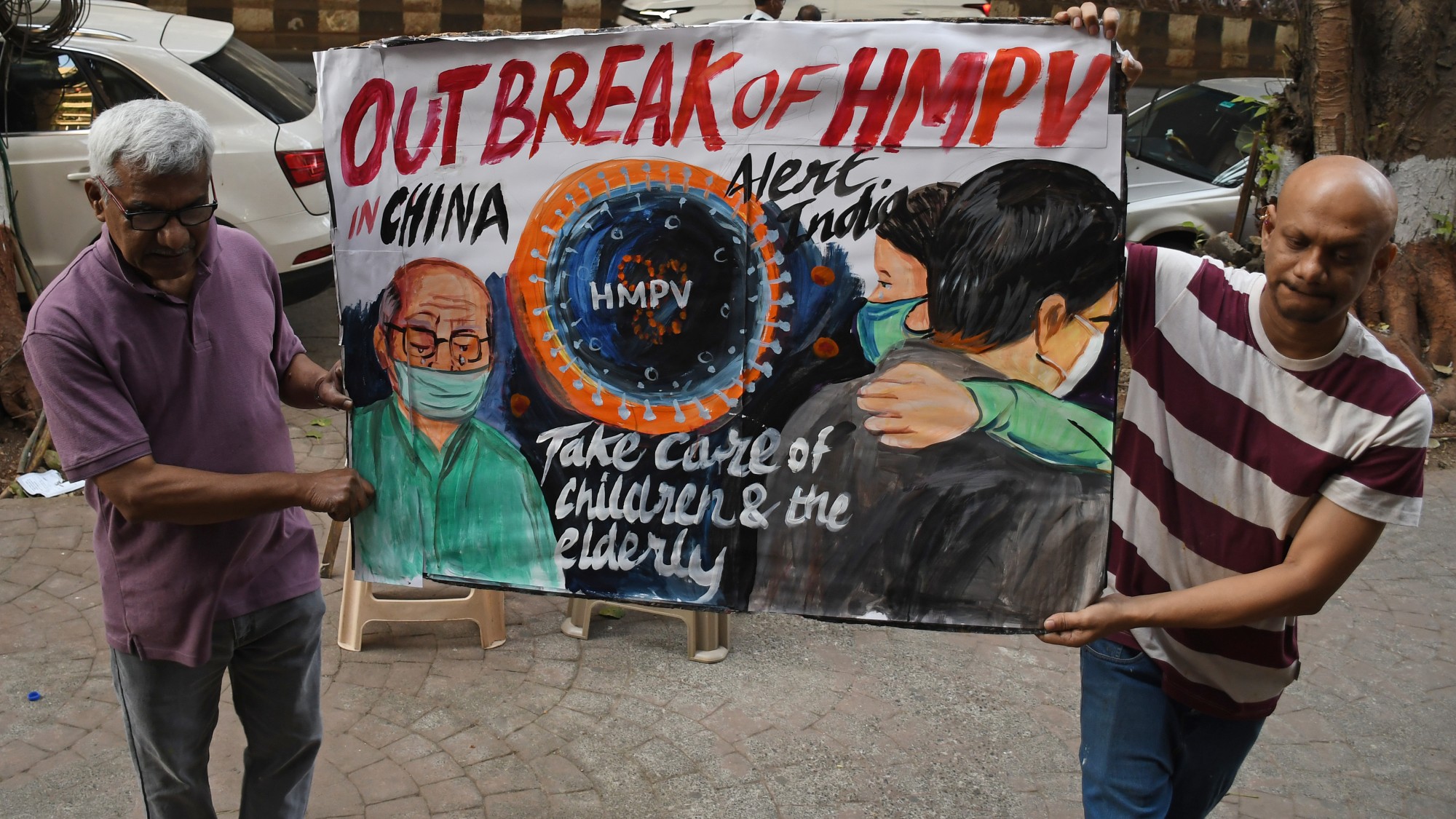

HMPV is spreading in China but there's no need to worry

HMPV is spreading in China but there's no need to worryThe Explainer Respiratory illness is common in winter